Bartolomé Esteban Murillo Painter: The Remarkable Spanish Baroque Master

Born: Late December 1617, Seville, Crown of Castile

Death: April 3, 1682, Seville, Crown of Castile

Art Movement: Baroque

Nationality: Spanish

Influenced By: Juan del Castillo, Francisco de Zurbarán, Jusepe de Ribera, and Alonso Cano

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo Painter: The Remarkable Spanish Baroque Master

Life and Education of Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo emerged as Spain’s most celebrated Baroque religious painter in the 17th century. His journey from humble beginnings to artistic prominence was shaped by personal hardships, formal training, and the vibrant cultural environment of Seville.

Early Years and Family Background

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo was born in Seville in late December 1617 and baptized on January 1, 1618. He was the youngest of fourteen children born to Gaspar Esteban, a barber-surgeon, and María Pérez Murillo.

Adoration of the Shepherds (c. 1668) by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Tragedy struck early in Murillo’s life. His father died when he was nine years old, and his mother passed away just one year later. This left the young Bartolomé orphaned and under the care of his older sister and her husband.

Despite these hardships, Murillo’s artistic talents emerged early. Growing up in Seville, then a wealthy port city with strong connections to the Americas, exposed him to various cultural influences that would later shape his artistic style.

Artistic Training with Juan del Castillo

Murillo’s formal artistic education began around age 10 when he apprenticed with his relative Juan del Castillo, a respected local painter. This apprenticeship lasted until Murillo was around 20 years old.

Under Castillo’s guidance, Murillo learned the basics of painting technique, color mixing, and composition. He assisted in his master’s workshop, helping with minor elements of paintings and gradually taking on more complex tasks.

Castillo’s conservative style emphasized clear outlines and flat colors. This foundation would later be transformed by Murillo as he developed his own softer, more atmospheric approach.

During this period, Murillo also studied the works of other Sevillian masters displayed in local churches and monasteries, allowing him to absorb various influences beyond his formal training.

Influences and Contemporaries

After completing his apprenticeship, Murillo was deeply influenced by studying the works of Velázquez and Zurbarán, two giants of Spanish painting. Their attention to realism and dramatic lighting shaped his early style.

The Marriage Feast at Cana (c. 1672) by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Around 1642, Murillo may have traveled to Madrid, where he likely encountered the royal art collections. These included masterpieces by Titian, Rubens, and van Dyck, which inspired his use of color and fluid brushwork.

The art of Caravaggio also impacted Murillo’s development. He adapted these techniques but softened them to create his signature luminous style.

Unlike his contemporary Alonso Cano, who worked in a more classical manner, Murillo developed a warmer, more accessible approach that resonated strongly with both religious and secular patrons.

Personal Life: Beatriz Cabrera and Progeny

In 1645, Murillo married Beatriz Cabrera y Villalobos, a woman from a respectable family. Their union marked a period of personal stability for the artist.

The couple had nine children together, though several died in infancy—a common tragedy in 17th-century Europe. His surviving children appeared as models in some of his religious paintings, adding a personal touch to his sacred works.

Following Beatriz’s death in 1663, Murillo never remarried. Instead, he devoted himself to his art and the education of his children. His son Gaspar eventually followed in his footsteps and became a painter.

Despite his growing fame, Murillo lived a modest life focused on his family and faith. This personal piety informed his religious paintings, giving them the emotional depth and sincerity that made them so beloved.

Murillo’s Artistic Style and Signature Works

Jacob’s Dream (1660–1665) by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo developed a distinctive artistic style that combined religious devotion with technical brilliance. His work became known for its soft, luminous quality and emotional appeal that resonated with both aristocratic patrons and ordinary viewers.

Development of Baroque Artistic Expressions

Murillo’s early style showed strong influences from Spanish and Flemish traditions. He initially used strong contrasts of light and dark (chiaroscuro) similar to other Baroque painters of his time. His work from the 1640s displayed more defined outlines and stronger lighting effects.

As he matured, Murillo created his own unique version of Baroque style. He developed softer transitions between light and shadow, creating a luminous quality that became his trademark. This technique helped convey spiritual themes with greater emotional impact.

His compositions became increasingly complex yet harmonious. Unlike some Baroque artists who emphasized drama and tension, Murillo often created scenes of gentle devotion and spiritual serenity.

Religious Iconography in Murillo’s Work

Religious subjects formed the core of Murillo’s artistic output. His numerous paintings of the Immaculate Conception became particularly famous. In these works, the Virgin appears floating on clouds, surrounded by cherubs and bathed in golden light.

The Adoration of the Shepherds (c. 1650) by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

His altarpieces for Seville’s churches also showcase his ability to create powerful devotional images. The “Virgin and Child” was another frequent theme, portrayed with remarkable tenderness and humanity that made divine subjects approachable.

Murillo depicted biblical scenes with both theological accuracy and emotional resonance. His work for the Charity Hospital in Seville illustrated biblical acts of mercy with touching realism.

Unlike more severe religious art of the time, Murillo’s religious paintings invite viewers to connect emotionally rather than merely instruct them in doctrine.

Portrayal of Women and Children

Murillo’s depictions of women and children reveal his exceptional ability to capture humanity and innocence. His “Young Beggar” (housed in the Louvre) portrays a poor boy with dignity and compassion rather than as an object of pity.

Children in Murillo’s paintings appear natural and lively rather than as miniature adults. He captured their spontaneous gestures and expressions with remarkable authenticity.

His portrayals of women, particularly in religious contexts, combine idealized beauty with genuine human warmth. The women in his paintings often display a quiet strength and tenderness.

Murillo’s genre scenes of ordinary people, especially children at play or selling fruits, show his keen observation of daily life in Seville. These works gained popularity throughout Europe for their charm and accessibility.

Later Years and Evolution of Style

In his later career, Murillo developed what became known as his “estilo vaporoso” or vaporous style. This technique featured softer contours, delicate color harmonies, and an almost misty atmosphere that created ethereal effects.

The Holy Family with a Little Bird (c. 1645–1650)

His palette shifted toward lighter, more luminous tones in these years. Works from this period show remarkable technical freedom with looser brushwork that anticipated much later artistic developments.

The paintings created for Cádiz Cathedral shortly before his death represent the culmination of this mature style. Though he died after falling from scaffolding while working on this commission, these final works show his powers undiminished.

Museums including the Prado in Madrid and the Museum of Fine Arts in Seville preserve excellent examples of this later style. These works continue to demonstrate why Murillo remained one of Europe’s most admired painters well into the 19th century.

Legacy and Influence on Future Generations

Bartolomé Esteban Murillo’s artistic contributions extended far beyond his lifetime, shaping the development of Spanish art and influencing painters across Europe for centuries after his death in 1682.

Academia de Bellas Artes and Spanish Painters

Murillo’s impact on Spanish art was formalized through the Academia de Bellas Artes, which embraced his technical approach and religious themes. His soft, luminous style became a standard that young Spanish painters studied and emulated throughout the 18th and 19th centuries.

Rest on the Flight into Egypt (c. 1665) by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo

Many Spanish artists traveled to Seville specifically to study Murillo’s works. His techniques for depicting light and creating emotional religious scenes became fundamental elements in Spanish artistic training.

The Prado Museum in Madrid houses several masterpieces by Murillo, making his work accessible to generations of Spanish artists who sought to understand his unique blend of realism and idealism.

Murillo’s Impact Beyond Seville

Murillo’s influence spread well beyond his hometown of Seville and throughout Europe. His works became highly sought after by collectors in France, England, and other European countries during the 18th century.

British collectors were particularly enthusiastic about acquiring Murillo’s paintings. This international interest helped cement his reputation as one of Spain’s greatest painters alongside Velázquez.

The National Gallery of Art in Washington DC displays important works by Murillo in its West Building, bringing his artistic legacy to American audiences. His paintings of religious subjects and street children continue to resonate with viewers across cultural boundaries.

Preservation and Display of Murillo’s Art

The Museum of Fine Arts in Seville maintains a significant collection of Murillo’s paintings, preserving his artistic legacy in the city where he lived and worked. Careful restoration efforts have ensured these works remain vibrant for future generations.

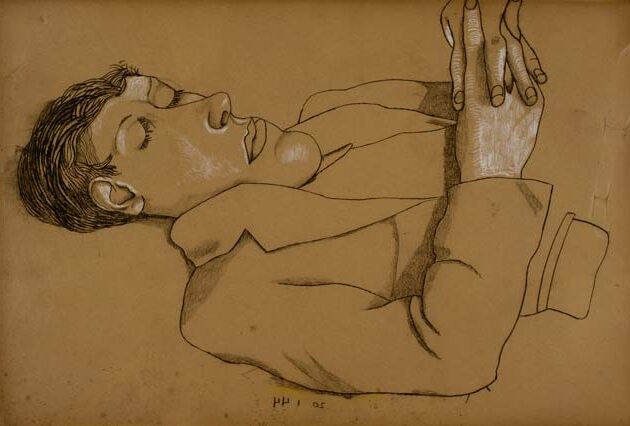

Joseph and Potiphar’s Wife (c. 1640–1645)

Modern technology has allowed art historians to study Murillo’s painting techniques in unprecedented detail. These analyses reveal his sophisticated layering methods and use of light, providing insights for contemporary artists.

Digital archives now make Murillo’s complete works accessible to students and researchers worldwide. This broader access has sparked renewed interest in his contributions to art history and his unique ability to blend emotional depth with technical brilliance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Murillo’s legacy as Spain’s most popular Baroque religious painter has sparked many questions about his life, work, and influence. His 17th-century paintings continue to fascinate art enthusiasts and scholars alike.

What are the most famous works of Bartolomé Esteban Murillo?

Murillo created numerous masterpieces during his career in Seville. “The Immaculate Conception” series stands among his most celebrated works, featuring ethereal depictions of the Virgin Mary.

“The Young Beggar” and “Two Women at a Window” showcase his talent for capturing everyday Spanish life with remarkable sensitivity. These genre paintings demonstrate his versatility beyond religious themes.

His “Self-Portrait” (c. 1670) offers a rare glimpse of the artist himself, displaying the technical mastery that made him famous throughout Europe.

How did Bartolomé Esteban Murillo contribute to the art world?

Murillo developed a distinctive soft, ethereal painting style that influenced generations of artists. His technique of using warm colors and gentle light created an atmosphere of tenderness in his religious works.

He founded the Seville Academy of Art in 1660, establishing the first formal art school in the city. This institution helped train many younger Spanish artists and formalized artistic education in the region.

Murillo’s ability to blend idealized religious imagery with authentic Spanish character created a unique artistic identity that resonated across Europe.

What was the impact of Spanish culture on Murillo’s artwork?

The deeply Catholic atmosphere of 17th-century Seville profoundly shaped Murillo’s religious paintings. Local religious institutions provided most of his commissions, reflecting the city’s devout character.

Murillo incorporated everyday Spanish people as models in his religious scenes. This approach connected sacred stories to the local population and gave his work an authentic Spanish flavor.

The artist’s genre paintings captured the street life of Seville with remarkable authenticity, documenting Spanish urban culture during the Baroque period.

Which museums house significant collections of Murillo’s paintings?

The Museo del Prado in Madrid holds an impressive collection of Murillo’s masterpieces. Visitors can experience the full range of his artistic development in this premier Spanish institution.

The Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg features several important works, reflecting Murillo’s popularity among European collectors outside Spain.

London’s Wallace Collection and National Gallery contain notable examples of his work. The Louvre in Paris and museums in Seville also display significant pieces by the Spanish master.

How are Murillo’s paintings valued and authenticated today?

Murillo’s works command high prices at auction, with major paintings selling for millions. His status as Spain’s most popular Baroque religious painter ensures continued market value.

Authentication involves technical analysis of pigments, canvas, and brushwork characteristic of his style. Art historians carefully examine provenance records to trace ownership history back to the 17th century.

Infrared reflectography and x-ray analysis help experts distinguish genuine Murillo paintings from the many copies and imitations created after his death.

What were the primary themes depicted in Murillo’s religious paintings?

The Immaculate Conception became Murillo’s signature religious theme. He painted this subject numerous times. He perfected his vision of the Virgin surrounded by cherubs and heavenly light.

Scenes from the life of Christ featured prominently in his work. His tender depictions of the Holy Family and the Christ Child resonated deeply with Spanish Catholic audiences.

Saints and martyrs appeared frequently in his commissions for churches and monasteries. Murillo portrayed these religious figures with a combination of spiritual transcendence and human warmth that defined his unique approach.