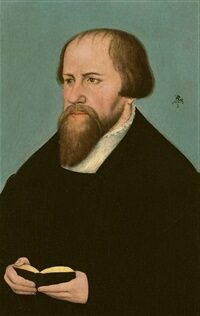

Lucas Cranach the Younger: Master Renaissance Painter of Northern Europe

Born: October 4, 1515, Wittenberg, Electorate of Saxony, Holy Roman Empire

Death: 25 January 1586, Wittenberg, Electorate of Saxony, Holy Roman Empire

Art Movement: German Renaissance

Nationality: German

Teacher: Lucas Cranach the Elder (His Father)

Lucas Cranach the Younger: Master Renaissance Painter of Northern Europe

Life and Career of Lucas Cranach the Younger

Lucas Cranach the Younger followed in his father’s footsteps to become one of the most significant German artists of the 16th century.

Born in 1515 in Wittenberg, he built upon his family’s artistic legacy while establishing his own reputation through paintings, workshop management, and civic service.

Family Legacy and Early Years

Lucas Cranach the Younger was born in 1515 in Wittenberg, Germany, as the second son of the renowned artist Lucas Cranach the Elder.

Christ and the Adulteress (1545–1550) by Lucas Cranach the Younger

From a young age, he trained in his father’s flourishing workshop alongside his older brother Hans.

The Cranach family workshop was already well-established when young Lucas began his artistic education. His father had cultivated relationships with nobility and religious reformers, setting a foundation for Lucas the Younger’s future connections.

Unlike many apprentices who traveled to study under different masters, Lucas remained in Wittenberg to learn the distinctive Cranach style directly from his father. This training emphasized technical precision, distinctive figural types, and efficient production methods.

When his brother Hans died unexpectedly in 1537, Lucas the Younger assumed greater responsibilities in the family business, preparing him for his future leadership role.

Leading the Workshop in Wittenberg

Following his father’s death in 1553, Lucas the Younger took complete control of the Cranach workshop in Wittenberg.

Under his leadership, the studio maintained its position as one of the most productive and influential artistic enterprises in Germany.

The workshop employed numerous apprentices and journeymen, creating a factory-like operation that could produce paintings, altarpieces, and portraits efficiently.

Lucas successfully preserved the distinctive “Cranach style” while subtly introducing his own artistic innovations.

His business acumen proved as sharp as his artistic skills. He managed commissions from royalty, nobility, and wealthy merchants across German territories.

While continuing religious subjects that had been workshop staples, Lucas the Younger adapted to changing tastes by producing more secular works. He maintained the workshop’s reputation for high-quality craftsmanship and distinctive visual language.

Relationship with Prominent Figures

Lucas Cranach the Younger maintained the close relationship his father had established with Martin Luther and other Protestant reformers. This connection influenced both his artistic output and social standing in Wittenberg.

Elijah and Baal’s Priests by Lucas Cranach the Younger

His workshop produced numerous portraits of Luther and other Reformation leaders, helping to disseminate their images and ideas throughout German territories. These works served both artistic and propaganda purposes.

The Cranach family’s ties to the Saxon court remained strong under Lucas the Younger. He served several Electors of Saxony, creating portraits and decorative works for their residences and public buildings.

These powerful connections ensured a steady stream of prestigious commissions. The Electors’ patronage provided both financial security and elevated social status for Lucas and his growing workshop.

Political Roles and Responsibilities

Beyond his artistic career, Lucas Cranach the Younger became deeply involved in Wittenberg’s civic affairs. He served multiple terms as the city’s mayor, demonstrating his standing in the community.

His political responsibilities included overseeing city finances, mediating disputes, and representing Wittenberg’s interests to higher authorities. These civic duties required significant time away from his artistic work.

As a prominent citizen, Lucas owned considerable property in Wittenberg and surrounding areas. His economic and political influence extended well beyond artistic circles.

Despite these demanding civic roles, he maintained artistic productivity throughout his life. The workshop continued operations under his guidance until his death in 1586 at age 71, ending the direct Cranach family involvement in the enterprise that had shaped German Renaissance art for nearly a century.

Artistic Style and Contributions

Lucas Cranach the Younger developed a distinctive artistic identity while building upon his father’s Renaissance techniques.

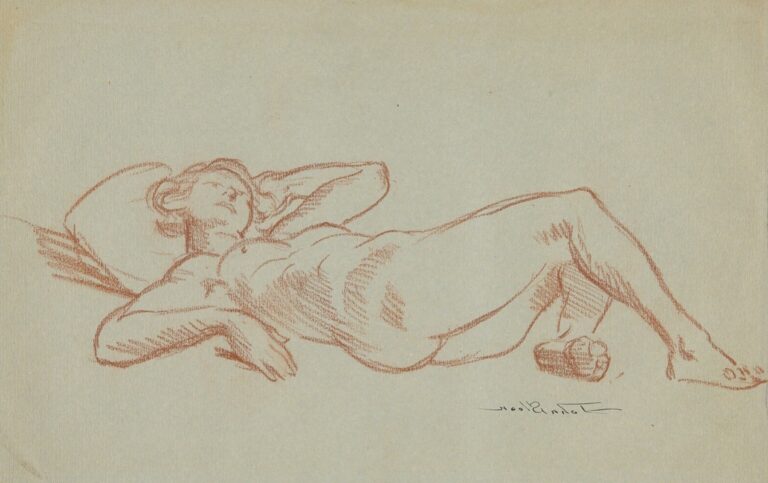

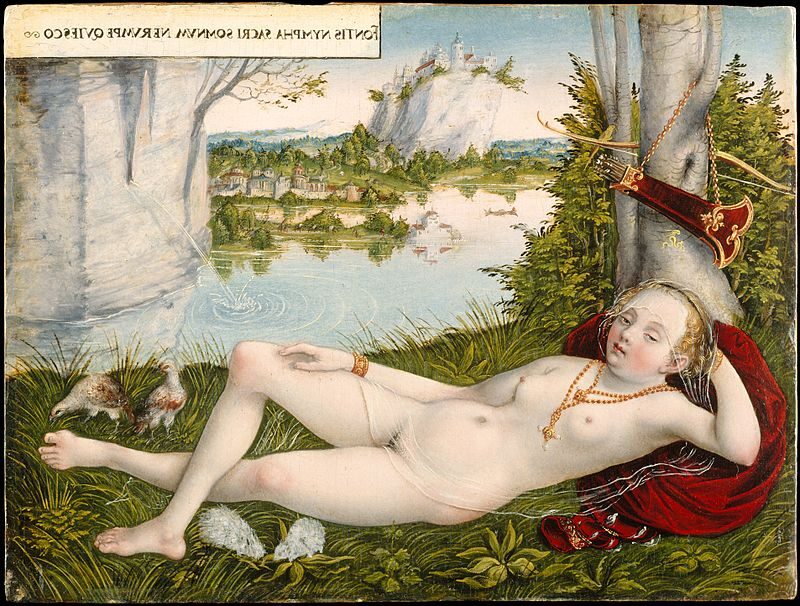

Nymph of the Spring (1545–1550) by Lucas Cranach the Younger

His style combined Protestant ideals with humanistic artistry, creating works that served both religious and secular purposes in 16th-century Germany.

Development of Painting Techniques

Lucas Cranach the Younger initially trained in his father’s workshop, where he mastered the elder Cranach’s techniques for oil on panel painting.

He gradually developed his own approach, characterized by smoother modeling of figures and more subtle color transitions than his father’s work.

His compositions often featured meticulous attention to detail, particularly in costume elements and decorative objects. The younger Cranach excelled at creating luminous skin tones and precise facial features.

By the 1550s, he began experimenting with oil on copper, a technique that allowed for exceptionally smooth surfaces and brilliant colors. This medium proved particularly effective for smaller devotional pieces and portraits.

His workshop employed standardized methods that maintained consistency across numerous commissions while allowing for artistic growth and adaptation to changing tastes.

Prominent Works and Themes

Religious subjects dominated Cranach the Younger’s output, reflecting the Protestant Reformation’s influence. His altarpieces often depicted biblical narratives in contemporary settings, making theological concepts accessible to ordinary viewers.

Notable works include the Wittenberg Altarpiece (1547) and the Weimar Altarpiece (1555), which blend religious symbolism with portraiture of prominent Reformation figures. These pieces demonstrate his skill in balancing theological messaging with artistic merit.

Cranach frequently incorporated symbolic elements like the snake with bat wings (the Cranach family emblem) as a signature in his compositions. His secular works included mythological scenes and portraits of nobility, often featuring women adorned with jewelry like rubies.

His portraits captured both physical likeness and social status through careful attention to clothing, posture, and attributes.

Innovations in Engraving and Woodcut

Beyond painting, Cranach the Younger made significant contributions to printmaking. His woodcut designs simplified complex religious concepts into visually compelling images that could be widely distributed.

He developed techniques for creating more nuanced tonal variations in prints, allowing for greater visual depth. His engravings often featured finer lines and more delicate details than earlier German printmakers.

Cranach’s workshop produced illustrated pamphlets supporting Lutheran ideas, combining text and images to communicate effectively with both literate and illiterate audiences. These prints helped standardize Protestant iconography across German-speaking regions.

His printmaking innovations included experimental combinations of techniques and improvements in reproducing complex textures in two dimensions.

Legacy and Influence on Art

Cranach the Younger’s workshop ensured the continuation of the Cranach style well into the latter half of the 16th century. His artistic approach influenced generations of German painters, particularly in Protestant regions.

Christ Blessing the Children (1545–1550) by Lucas Cranach the Younger

His systematic workshop practices established standards for art production that balanced efficiency with quality. Many of his apprentices went on to successful careers, spreading his techniques throughout Central Europe.

Museums worldwide now preserve his artwork, with major collections in Berlin, Dresden, and Weimar. Art historians increasingly recognize his distinct contributions rather than viewing him merely as his father’s successor.

His integration of Renaissance aesthetics with Protestant theology helped create a visual language that shaped German art for more than a century after his death.

Major Works and Their Historical Context

Lucas Cranach the Younger produced significant artworks that reflected the religious and social changes of the Reformation era. His versatile talent showed in his portraits of religious leaders, mythological scenes, and biblical narratives that carried both artistic and political importance.

Portraits of Reformation Leaders

Cranach the Younger created numerous portraits of Martin Luther and Philipp Melanchthon, continuing his father’s role as the primary visual chronicler of the Protestant Reformation. These portraits weren’t merely decorative but served as powerful propaganda tools that helped spread Reformation ideas.

John the Baptist Preaching by Lucas Cranach the Younger

His Portrait of Martin Luther shows the religious leader with characteristic intensity and determination. The simple backgrounds and focus on facial features emphasized Luther’s intellectual authority rather than worldly status.

Similarly, his Portrait of Philipp Melanchthon captured the scholarly nature of Luther’s important collaborator. These works circulated widely as prints and paintings, helping ordinary people connect with Reformation leaders.

Cranach’s portrait style featured realistic facial details with simplified clothing and backgrounds, making these images instantly recognizable and memorable to viewers.

Depictions of Mythology and Virtue

Cranach the Younger also explored mythological themes and allegorical subjects that were popular during the Renaissance. His Nymph of the Spring (1545-1550) shows his skill in depicting the female form in idealized natural settings.

The painting Lucretia, depicting the Roman heroine, explored themes of virtue and sacrifice that resonated with both Renaissance humanism and Protestant values. These works often contained moral messages compatible with Reformation thinking.

His allegorical painting Caritas (Charity) demonstrated his ability to merge classical ideas with Christian virtues. The work shows a woman surrounded by children, representing the theological virtue of charity.

These mythological works can be found in prestigious collections including the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna and the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Religious Narratives and Commissions

Cranach’s religious paintings reflect both Protestant theology and traditional Christian narratives. Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery (1545-1550) shows his interest in biblical scenes that emphasized Christ’s mercy and forgiveness.

Christ and the Woman Taken in Adultery (1545–1550) by Lucas Cranach the Younger

Christ Blessing the Children (1545-1550) highlights themes particularly important to Protestant thinking: the direct relationship between believers and Christ without priestly intervention. This subject became especially popular during the Reformation era.

His religious works often appeared in church altarpieces and public spaces. Many featured detailed backgrounds and rich colors that made biblical stories accessible to viewers.

Cranach also created practical religious art like illustrated Bibles and prayer books. His workshop produced numerous Coat of Arms designs for noble patrons, blending religious symbolism with family heritage.

Examples of his religious work can be viewed at the National Gallery of Art and the Museum of Fine Arts, demonstrating his lasting influence on religious art in Germany and beyond.

Frequently Asked Questions

Lucas Cranach the Younger’s artistic legacy generates many inquiries about his style, influences, and historical impact. His relationship with his famous father, his connections to Reformation figures, and his distinctive artistic contributions continue to fascinate art historians and enthusiasts alike.

What distinguishes the artistic style of Lucas Cranach the Younger from his contemporaries?

Lucas Cranach the Younger developed a style that blended his father’s techniques with his own innovations. He maintained the family workshop’s distinctive thin, elegant figures and detailed backgrounds.

His work featured more naturalistic facial expressions than many contemporaries. This softer approach differentiated his portraits from the sometimes harsher Renaissance styles of the period.

Cranach the Younger also incorporated more detailed landscapes and architectural elements than many of his peers. His paintings often included rich colors and meticulous attention to fabric textures and patterns.

Which notable historical figures did Lucas Cranach the Younger paint?

Cranach the Younger painted numerous Protestant reformers, including multiple portraits of Martin Luther and his wife Katharina von Bora. These became important visual documents of the Reformation movement.

He also created portraits of several Saxon electors and their families, continuing his father’s role as court painter. These included Friedrich III the Wise and his successors.

Religious and academic figures of the era frequently commissioned Cranach the Younger for portraits. His position in Wittenberg, a center of Reformation activity, gave him access to many influential people.

What influence did Lucas Cranach the Elder have on the Younger’s work?

The Elder Cranach served as his son’s primary teacher and artistic influence. Young Lucas learned in his father’s workshop, mastering the family style and techniques that became their trademark.

The workshop practices established by the Elder influenced his son’s productive career. The younger Cranach inherited not only artistic techniques but also business connections and the prestigious position of court painter.

Many early works by Cranach the Younger are difficult to distinguish from his father’s paintings. The seamless transition between their styles shows the profound influence the father had on his son’s artistic development.

How did Lucas Cranach the Younger contribute to the Reformation through his art?

Cranach the Younger created visual propaganda that helped spread Protestant ideas. His accessible paintings of Biblical scenes emphasized Reformed theology and made complex religious concepts understandable to common people.

He continued his father’s tradition of creating “Law and Gospel” paintings that illustrated Lutheran theological principles. These works showed the contrast between salvation through faith versus works.

His numerous portraits of Reformation leaders helped establish their public image. These portraits were often reproduced and distributed, making figures like Luther recognizable throughout German territories.

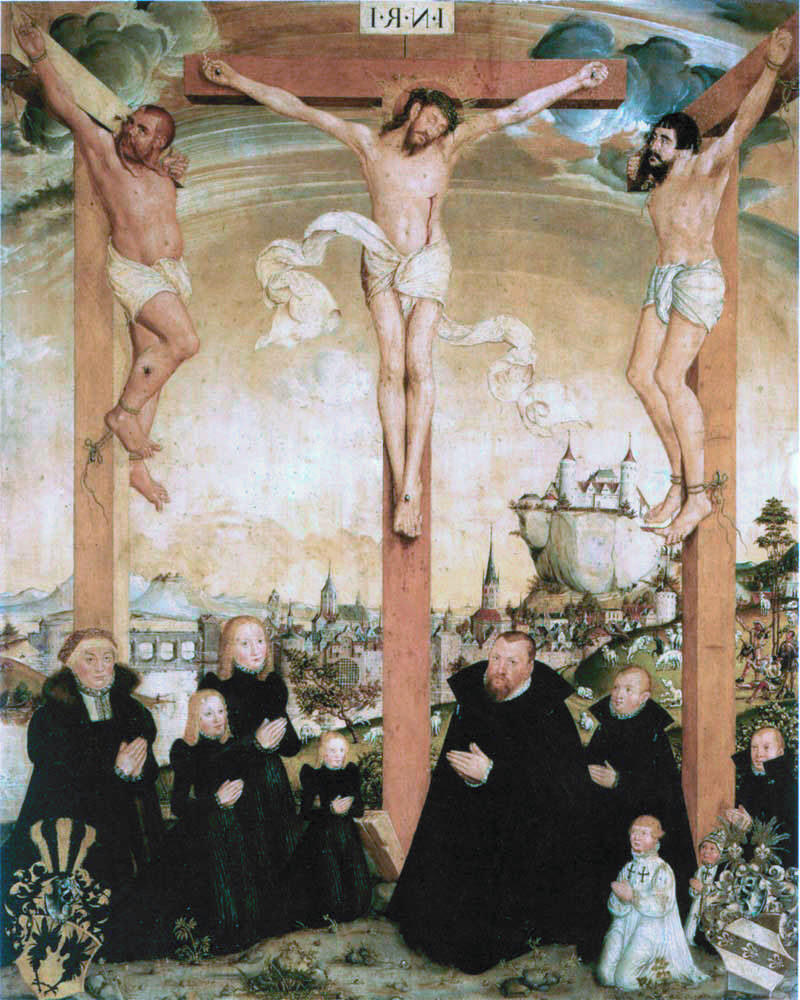

What are some of the most celebrated works of Lucas Cranach the Younger?

The “Wittenberg Altarpiece” stands as one of Cranach the Younger’s most significant works. This piece showcases Lutheran theology through visual storytelling and includes portraits of Reformation figures.

His portrait series of Martin Luther demonstrates his skill in capturing both physical likeness and personality. These portraits became definitive images of Luther for generations of Protestants.

The “Crucifixion” (1555) represents his mature style and theological depth. This painting balances religious symbolism with Renaissance artistic techniques in a way that resonated with Protestant audiences.

How did the political climate of the time affect Lucas Cranach the Younger’s artwork?

The religious tensions of the Reformation period directly influenced Cranach’s subject matter and symbolism. His work often needed to carefully navigate political sensitivities while still promoting Protestant ideas.

Cranach benefited from the protection of Protestant Saxon electors. Their patronage allowed him artistic freedom to create works supporting Reformation ideas when such activities could be dangerous elsewhere.

As religious conflicts intensified, Cranach adjusted his style to include more explicit Protestant themes. His later works more boldly presented Lutheran theological concepts as Protestantism became more established in German territories.