Michelangelo Buonarroti Painter: The Renaissance Master Behind the Sistine Chapel

Born: 6 March 1475, Caprese, Republic of Florence

Death: 18 February 1564, Rome, Papal States

Art Movement: High Renaissance, Mannerism

Nationality: Italian

Teachers: Domenico Ghirlandaio and Bertoldo di Giovanni

Institution: Platonic Academy

Michelangelo Buonarroti Painter: The Renaissance Master Behind the Sistine Chapel

Early Life and Training

Michelangelo’s formative years set the foundation for his extraordinary artistic career. His childhood and early training exposed him to influential masters and powerful patrons who recognized his exceptional talent.

Origins in Caprese and Florence

Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni was born on March 6, 1475, in Caprese, a small town in Tuscany, Italy. His family had belonged to minor Florentine nobility for several generations.

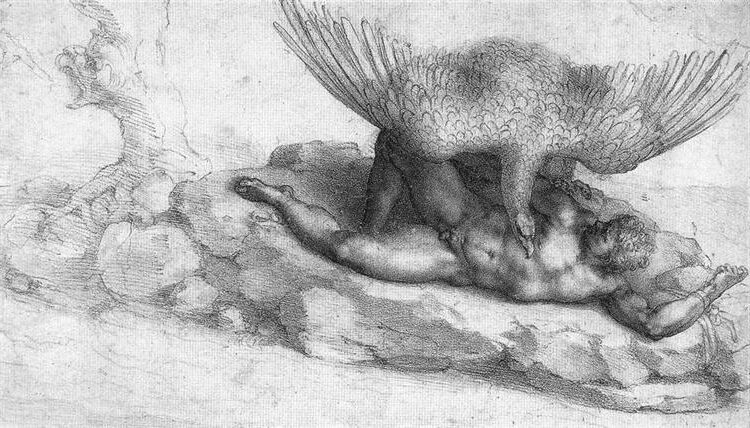

The Punishment of Tityus by Michelangelo in 1532

When Michelangelo was still young, his family moved to Florence, the thriving center of Renaissance art and culture. This move proved crucial for his artistic development.

His mother died when he was only six years old, leaving him to be raised by his father and a stonecutter’s family. Despite his father’s initial resistance to his artistic ambitions, Michelangelo’s talent was undeniable.

Early Artistic Influence and Education

At age 13, Michelangelo became an apprentice to painter Domenico Ghirlandaio, one of Florence’s most prominent fresco painters. This arrangement was unusual as most apprenticeships began earlier.

His exceptional skill caught the attention of Lorenzo de’ Medici, the powerful ruler of Florence. In 1490, Michelangelo moved to the Medici palace where he studied for two years under sculptor Bertoldo di Giovanni.

During this time, he gained access to the Medici’s remarkable collection of ancient Roman sculptures and connected with humanist scholars and poets. He studied the works of earlier masters like Giotto, Masaccio, and Donatello.

This period ended with Lorenzo’s death in 1492, but these formative experiences shaped Michelangelo’s artistic vision and technical abilities.

Masterworks and Key Projects

Michelangelo created extraordinary works across multiple artistic disciplines during his long career. His mastery of sculpture, painting, and architecture resulted in some of the most recognized masterpieces in Western art history.

Sculptural Achievements

Michelangelo’s sculptures reveal his exceptional ability to transform marble into seemingly living forms. The Pietà (1498-1499), created when he was only 24, showcases his early talent. This remarkable work depicts the Virgin Mary holding the dead Christ with astonishing technical precision and emotional depth.

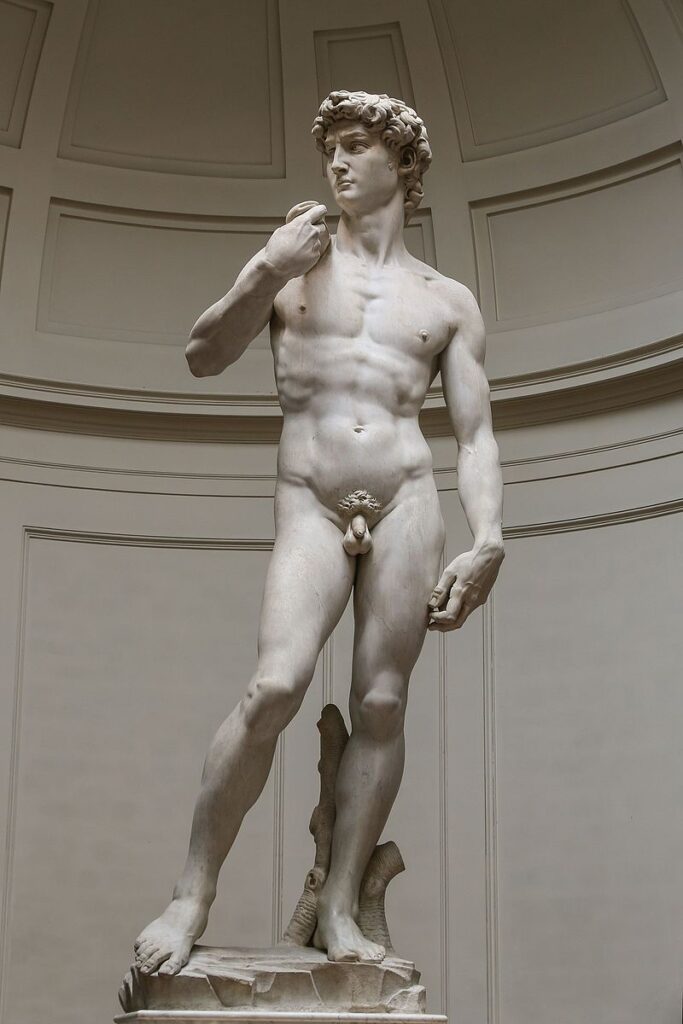

His colossal David (1501-1504) stands 17 feet tall and represents the artist at the height of his sculptural powers. Unlike previous versions, Michelangelo’s David appears alert and tense, capturing the moment before battle with Goliath.

The powerful Moses (1513-1515), created for Pope Julius II’s tomb, shows the biblical leader with muscular intensity and emotional force. The figure’s imposing presence and detailed features demonstrate Michelangelo’s ability to infuse stone with life-like energy.

These sculptures exemplify Renaissance ideals through their anatomical accuracy, emotional expressiveness, and classical inspiration.

Painting the Sistine Chapel

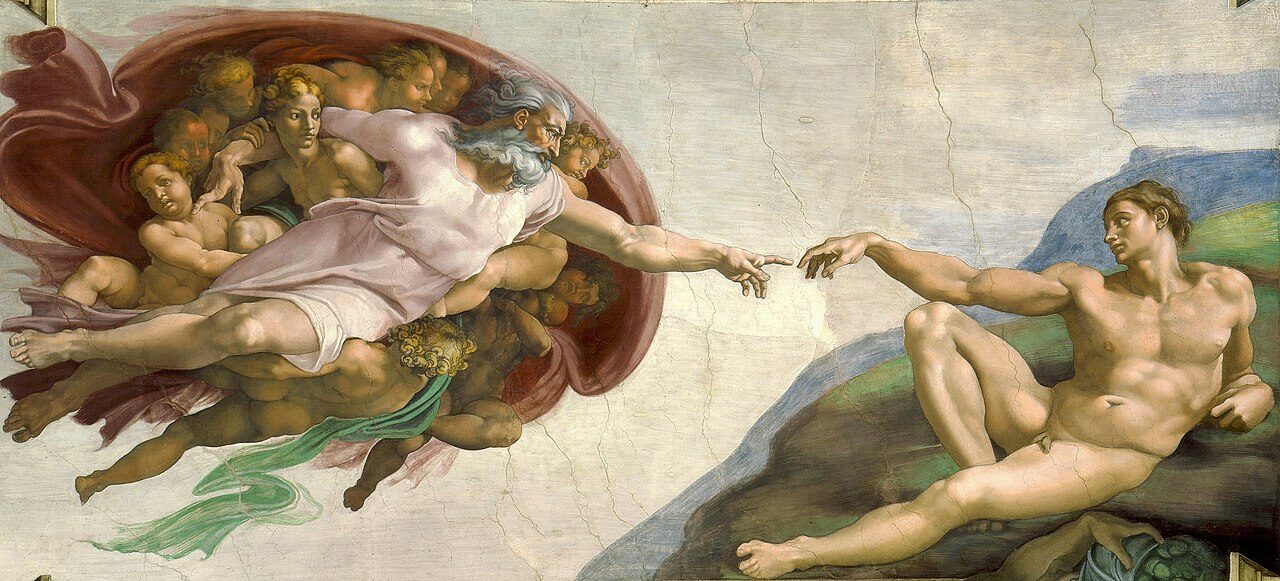

The Sistine Chapel ceiling (1508-1512), commissioned by Pope Julius II, stands as one of Michelangelo’s most ambitious projects. Despite considering himself primarily a sculptor, Michelangelo created this monumental 5,000-square-foot fresco masterpiece.

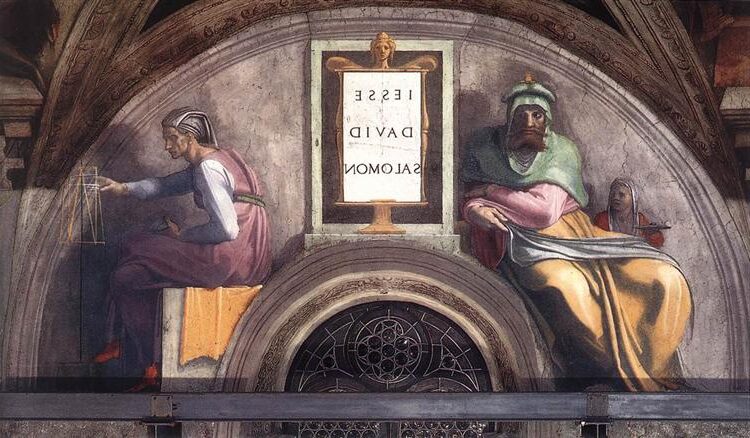

The ceiling depicts scenes from Genesis, including the iconic “Creation of Adam” where God reaches out to touch Adam’s finger. Michelangelo painted over 300 figures across nine central panels, surrounded by prophets, sibyls, and ancestors of Christ.

Working in difficult conditions, often lying on his back on high scaffolding, Michelangelo completed this extraordinary work in four years. His use of vibrant colors, dynamic compositions, and idealized human forms revolutionized painting.

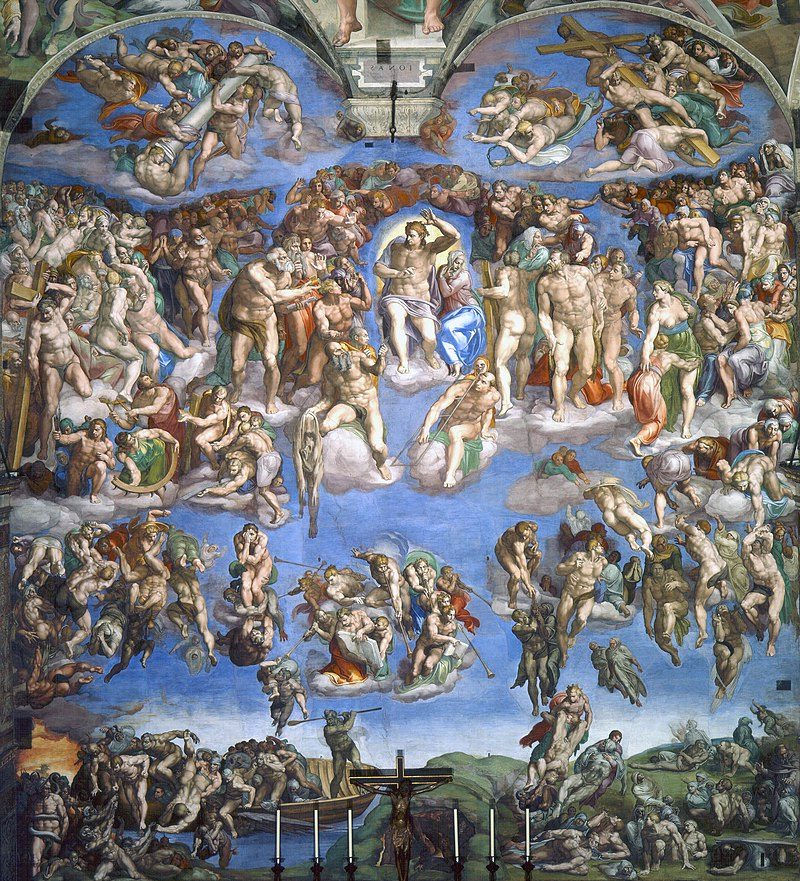

Years later, Michelangelo returned to paint “The Last Judgment” (1536-1541) on the chapel’s altar wall. This dramatic scene depicts Christ judging souls with swirling, muscular figures showing Michelangelo’s evolved artistic style.

Architectural Contributions

Michelangelo’s architectural genius emerged later in his career but proved equally significant. For the Laurentian Library in Florence (designed 1523-1525), he created an innovative staircase and reading room that broke from classical traditions with dynamic, unexpected elements.

Laurentian Library in Florence (designed 1523-1525)

His redesign of Rome’s Piazza del Campidoglio transformed a disorganized space into a harmonious civic center that still impresses visitors today. The trapezoidal plaza with its distinctive paving pattern demonstrates his mastery of urban planning.

Perhaps his most significant architectural achievement was his work on the Dome of Saint Peter’s Basilica. Though he didn’t live to see it completed, Michelangelo’s design for the massive dome revolutionized Renaissance architecture with its double-shell construction and imposing presence.

His unfinished projects for the Basilica of San Lorenzo facade show his experimental approach to architectural design. These works reveal how Michelangelo approached architecture as a sculptor, treating buildings as three-dimensional forms to be shaped and molded.

Legacy and Impact on Art

The Ancestors of Christ: David, Solomon by Michelangelo in 1511

Michelangelo’s artistic innovations transformed Western art and influenced generations of artists after him. His mastery of human anatomy, emotional expression, and technical skill established him as one of the greatest artists in history.

Influence on Peers and Successors

Michelangelo’s work had an immediate impact on his contemporaries. Raphael was so impressed by Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel ceiling that he altered his own style and incorporated Michelangelo’s robust figures into his works.

Giorgio Vasari, the first art historian, called Michelangelo “il divino” (the divine one) and “the greatest living artist” in his influential book “Lives of the Artists.” This helped cement Michelangelo’s reputation for centuries to come.

The concept of “terribilità” – a term describing the emotional intensity and awesome quality of Michelangelo’s art – became a defining characteristic that later artists sought to emulate.

His anatomical precision and powerful figures directly influenced the Mannerist movement, which emerged in the 16th century. Artists like Pontormo and Rosso Fiorentino adopted his exaggerated proportions and dynamic poses.

Michelangelo’s Artistic Philosophy

Michelangelo believed that sculpture was the highest form of art because it most closely resembled divine creation. He famously stated that his role was merely to free the figures already existing within the marble.

Medici Madonna between St. Cosmas and St. Damian, 1531

Unlike Leonardo da Vinci, who approached art scientifically, Michelangelo worked more intuitively. He rarely made detailed preliminary drawings, preferring to work directly on the stone or surface.

His concept of the “Renaissance Man” – excelling in multiple disciplines – was embodied in his own life as a painter, sculptor, architect, and poet. This ideal of the complete artist influenced creative thinking for centuries.

Michelangelo rejected the notion that art should merely imitate nature. Instead, he believed art should improve upon nature by revealing inner truths and beauty hidden from ordinary sight.

Frequently Asked Questions

Michelangelo Buonarroti stands as one of history’s greatest artists whose works continue to inspire awe. His contributions to sculpture, painting, and architecture defined Renaissance art and influenced generations of artists.

What is Michelangelo best known for in the art world?

Michelangelo is best known for creating iconic masterpieces including the sculpture “David” and the ceiling frescoes in the Sistine Chapel. The Sistine Chapel ceiling, painted between 1508 and 1512, features over 300 figures and tells Biblical stories with unprecedented artistic skill.

His sculpture “David” represents the ideal male form and showcases his mastery of human anatomy. At 17 feet tall, this marble sculpture captures a moment of intense concentration before David’s battle with Goliath.

The “Pietà,” depicting Mary holding the body of Jesus, demonstrates his ability to transform marble into seemingly soft flesh and flowing fabric.

How did Michelangelo contribute to the Renaissance?

Michelangelo elevated Renaissance art through his unparalleled understanding of human anatomy and emotional expression. He studied cadavers to gain knowledge of muscles and bone structure, allowing him to create figures with realistic proportions and movement.

His work embodied Renaissance ideals by merging classical Greek and Roman influences with Christian themes. This synthesis helped define the artistic approach of the High Renaissance period.

Michelangelo’s innovations in composition and perspective changed how artists approached their craft. His techniques for creating depth and dimension influenced countless artists who followed.

Can you outline Michelangelo’s greatest achievements?

Michelangelo’s completion of the Sistine Chapel ceiling ranks among his greatest feats. He painted nearly 5,000 square feet of ceiling while working on scaffolding, often lying on his back for hours.

The creation of the massive “David” sculpture from a single block of marble that other sculptors had abandoned shows his extraordinary vision and skill. He transformed a flawed piece of stone into one of history’s most recognized artworks.

His design for St. Peter’s Basilica dome revolutionized architectural possibilities. Though not completed in his lifetime, his plans guided the construction of this iconic structure.

The “Last Judgment” fresco on the Sistine Chapel altar wall represents another monumental achievement with its complex composition and powerful emotional content.

What details are known about Michelangelo’s early life and education?

Born on March 6, 1475, in Caprese, Italy, Michelangelo grew up in Florence where his father served as a local government official. His mother died when he was only six years old.

Against his father’s wishes, Michelangelo apprenticed with painter Domenico Ghirlandaio at age 13. This formal training lasted only one year before he caught the attention of Lorenzo de’ Medici.

Michelangelo lived in the Medici household from 1490 to 1492, where he studied classical sculpture in their garden collection. Here, he learned from prominent humanist scholars and developed his understanding of ancient art.

What notable works did Michelangelo create beyond painting?

Michelangelo designed the Laurentian Library in Florence, creating an innovative staircase and reading room that broke from classical architectural traditions. His unique approach to space and form influenced architectural design for centuries.

As a poet, Michelangelo wrote hundreds of sonnets and madrigals that reveal his personal thoughts and spiritual struggles. These writings offer insights into his artistic philosophy and emotional life.

The Medici Chapel tombs feature his sculptures of “Night,” “Day,” “Dawn,” and “Dusk,” which represent some of his most psychologically complex figural works. These allegorical figures show his ability to express human emotion through stone.

Where can one find Michelangelo’s most significant artworks today?

The Sistine Chapel in Vatican City houses Michelangelo’s most extensive painting project. It includes the ceiling frescoes and “The Last Judgment.” Millions of visitors view these works annually.

The “David” sculpture stands in the Accademia Gallery in Florence, Italy. A replica marks the original location in the Piazza della Signoria.

St. Peter’s Basilica in Rome features Michelangelo’s architectural contributions and his early sculpture “Pietà.” The sculpture is now protected behind bulletproof glass.

The Louvre Museum in Paris displays his sculptures “Dying Slave” and “Rebellious Slave.” These were originally intended for Pope Julius II’s tomb.