John Everett Millais Painter: The Visionary Pre-Raphaelite Artist of Victorian England

Born: 8 June 1829, Southampton, Hampshire, England

Death: 13 August 1896, Kensington, London, England

Art Movement: Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

Nationality: British

Influenced By: Emily Mary Millais (née Evermy)- His Mother

Institution: Royal Academy of Art

John Everett Millais Painter: The Visionary Pre-Raphaelite Artist of Victorian England

Life and Background of John Everett Millais

John Everett Millais was a prominent British painter who rose to fame as a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. His extraordinary talent emerged at a young age and developed throughout his life as he navigated both professional success and personal relationships.

Early Life and Education

John Everett Millais was born on June 8, 1829, in Southampton, England, to a wealthy family from Jersey. His talent appeared remarkably early—he began drawing at age four and was considered something of a prodigy.

The Vale of Rest, 1858, by John Everett Millais

At just eleven years old, Millais became the youngest student ever admitted to the Royal Academy Schools in 1840. This extraordinary achievement highlighted his exceptional artistic abilities.

During his education, Millais met Dante Gabriel Rossetti and William Holman Hunt. Together in 1848, they formed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, a group that rejected conventional academic painting styles in favor of detailed, bright compositions inspired by early Renaissance art.

His early works like “Christ in the House of His Parents” (1850) demonstrated the Brotherhood’s principles but also sparked controversy for their realistic portrayals of religious subjects.

Personal Life and Relationships

Millais’s personal life became a subject of Victorian scandal when he fell in love with Effie Gray, who was married to the influential art critic John Ruskin. Their relationship developed while Millais was painting Ruskin’s portrait in Scotland.

After Effie’s marriage to Ruskin was annulled on grounds of non-consummation in 1854, she and Millais married in 1855. This highly publicized affair damaged Millais’s reputation temporarily but ultimately led to a happy marriage.

The couple had eight children together. Their family life was generally considered happy and stable, providing Millais with a supportive home environment for his artistic work.

As Millais’s career progressed, his style evolved away from strict Pre-Raphaelite principles. His marriage to Effie coincided with a shift toward more commercially successful works that appealed to Victorian tastes.

Death and Legacy

In his later years, Millais suffered from throat cancer. Despite his illness, he continued painting until shortly before his death on August 13, 1896, at the age of 67.

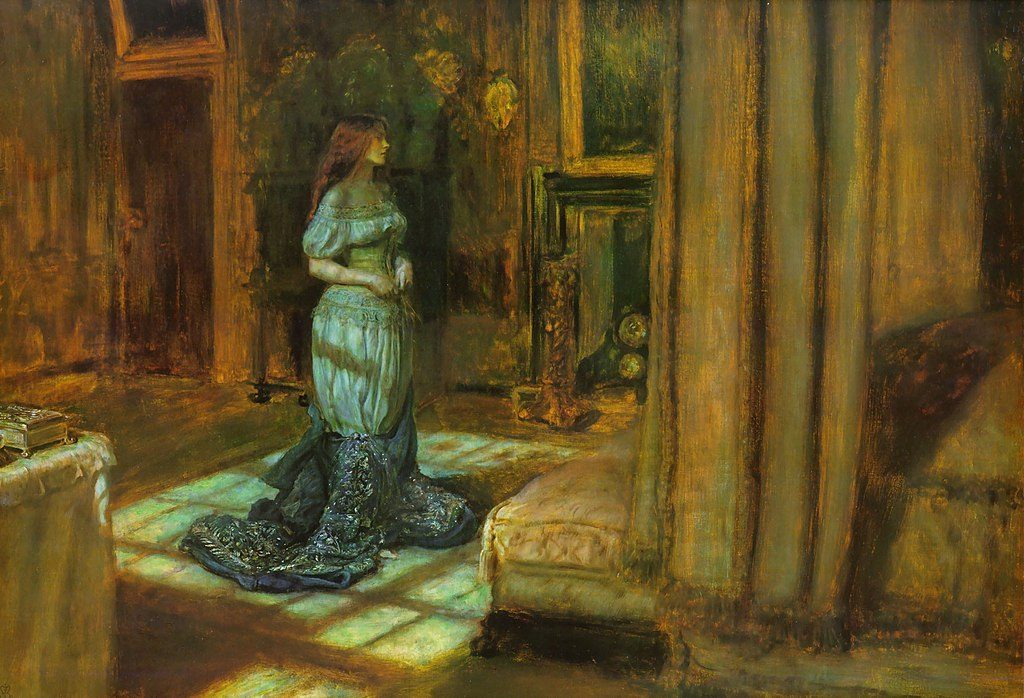

The Eve of Saint Agnes, 1863, by John Everett Millais

Before his death, Millais received the honor of becoming President of the Royal Academy, though he held the position for only a few months. He was also the first artist to be granted a hereditary baronetcy.

Millais left behind approximately 500 paintings, many of which remain famous today. Works like “Ophelia” (1851-52) and “Bubbles” (1886) continue to be celebrated as masterpieces of Victorian art.

His artistic legacy extends beyond his paintings. Millais helped transform British art through his early Pre-Raphaelite work and later influenced generations of artists. His technical skill and ability to capture emotion in his subjects ensure his place among Britain’s greatest painters.

Artistic Career and Works

John Everett Millais established himself as one of the most significant British painters of the Victorian era. His artistic journey spanned several distinctive periods, each marked by technical brilliance and evolving styles that influenced generations of artists.

Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood Foundation

In 1848, Millais co-founded the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (PRB) with William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. At just 19 years old, he rebelled against the Royal Academy’s conventional teachings and embraced a revolutionary approach to art.

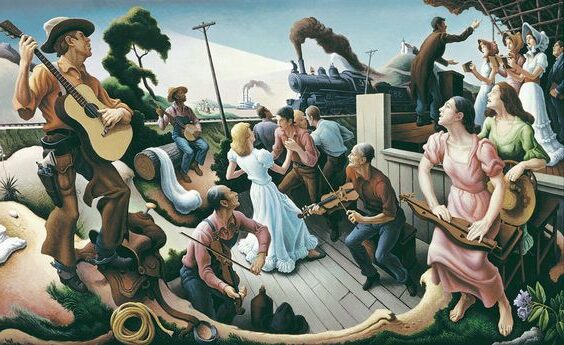

Pizarro Seizing the Inca of Peru, 1846, by John Everett Millais

The Brotherhood rejected the formulaic style of Renaissance painter Raphael and his followers. Instead, they advocated for truthfulness to nature, detailed realism, and rich colors. Millais demonstrated these principles in early works like “Isabella” (1849) and “Christ in the House of His Parents” (1850).

His meticulous attention to botanical accuracy and naturalistic detail became hallmarks of the movement. Though the formal Brotherhood lasted only a few years, its influence transformed British art permanently.

Notable Works and Recognition

Millais produced several masterpieces that secured his reputation. “Ophelia” (1851-52) stands as his most celebrated work, depicting Shakespeare’s character floating in a stream surrounded by meticulously rendered flora.

Ophelia, 1851–52, by John Everett Millais

“The Blind Girl” (1856) and “Autumn Leaves” (1856) showcased his technical brilliance and emotional depth. These works combined realistic detail with poetic symbolism.

His portrait “The Vale of Rest” (1858) demonstrated his evolving style while maintaining Pre-Raphaelite principles. Millais received numerous accolades during his lifetime, including election as an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1853.

In 1885, he was granted a baronetcy, becoming Sir John Everett Millais—the first artist to receive this honor. His works now hang in major museums worldwide, including the Tate Britain and Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Later Career and Stylistic Evolution

As Millais matured, his style shifted from detailed Pre-Raphaelite work toward broader brushstrokes and more commercial subjects. This evolution sparked criticism from former PRB colleagues but increased his popularity with the public.

His later paintings featured sentimental scenes and portraits of British high society. Works like “Bubbles” (1886) became widely recognized after Pears Soap purchased it for advertising.

Millais became President of the Royal Academy in 1896, shortly before his death. Despite his stylistic changes, his technical skills remained impressive throughout his career.

Art historians note that his later works, while less revolutionary than his early pieces, still displayed exceptional craftsmanship. His ability to adapt his style while maintaining artistic integrity demonstrates the versatility that made him one of Britain’s most successful painters.

Influence and Contribution to Art

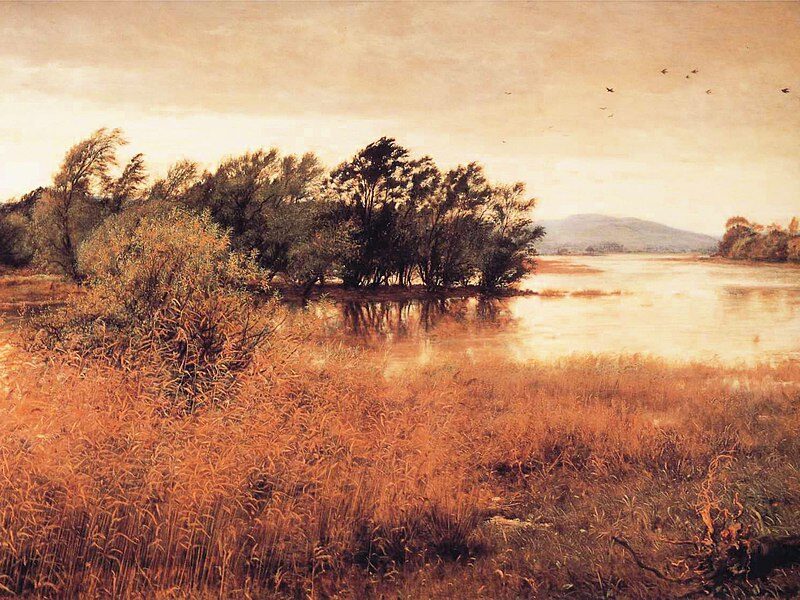

Chill October, 1870, by John Everett Millais

John Everett Millais transformed Victorian art through his technical brilliance and innovative approach. His work continues to inspire artists today, bridging classical techniques with modern sensibilities.

Impact on Victorian Art

Millais helped establish the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848, challenging the artistic conventions of the Royal Academy. His meticulous attention to detail and vibrant colors revolutionized Victorian painting standards.

His masterpiece “Ophelia” (1851-52) demonstrated his extraordinary technique, combining realistic natural settings with emotional storytelling. The painting remains one of the most recognized works of the era.

Millais’ portraits captured the Victorian spirit with remarkable psychological insight. His ability to blend technical precision with emotional depth elevated portraiture beyond mere representation.

As his career progressed, Millais gained widespread popularity, eventually becoming President of the Royal Academy in 1896. His commercial success helped legitimize new artistic movements during a period of rapid cultural change.

Influence on Future Generations

Millais’ technical innovations influenced numerous artistic movements, including Symbolism and Art Nouveau. His bold use of color and meticulous detail inspired artists like Vincent van Gogh and John Singer Sargent.

A Flood, 1870, by John Everett Millais

Contemporary artists continue to reference his work, particularly his approach to narrative painting. Modern exhibitions frequently showcase his paintings alongside current works to highlight his enduring relevance.

His illustrations for books and magazines helped establish visual storytelling techniques still used in modern media. Many graphic novelists and illustrators cite Millais as an important influence on their work.

The Brotherhood’s emphasis on truth to nature, championed by Millais, contributed to the development of both Realism and Impressionism in later decades.

Frequently Asked Questions

John Everett Millais left a lasting legacy in Victorian art. His techniques, subject choices, and evolution as an artist continue to fascinate art historians and enthusiasts alike.

What are the most renowned works of John Everett Millais?

Millais created several iconic paintings that remain celebrated today. “Ophelia” (1851-52) depicts Shakespeare’s character floating in a stream surrounded by detailed flora and is considered his masterpiece.

“Autumn Leaves” stands as one of his most atmospheric works, praised by contemporaries including Dante Gabriel Rossetti. “Christ in the House of His Parents” generated controversy for its realistic portrayal of the holy family.

Other notable works include “Bubbles,” which later became famous as an advertisement, and “The Boyhood of Raleigh,” which captures storytelling and imagination.

How did John Everett Millais influence the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood?

As a founding member of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848, Millais helped establish the movement’s core principles. His technical skill and attention to natural detail exemplified the group’s rejection of academic conventions.

Millais’ meticulous approach to painting directly from nature influenced fellow artists. His commitment to truthful representation and brilliant color helped define the Pre-Raphaelite aesthetic.

His early success brought attention to the movement’s goals and artistic vision. Even as he later moved away from strict Pre-Raphaelite principles, his early work remained influential to the movement’s identity.

In what ways did Millais’ style evolve over the course of his career?

Millais began with elaborate detail and rich colors typical of Pre-Raphaelite work. His early paintings featured meticulous observation of nature and symbolic elements.

By the 1860s, his style became broader and more fluid. He developed a more commercially appealing approach with looser brushwork and more conventional subject matter.

Later in his career, Millais focused on portraiture and landscapes with a simplified technique. This evolution reflected both artistic growth and practical considerations as he became one of Britain’s most successful artists.

Can you describe the relationship between John Everett Millais and the art critic John Ruskin?

Millais and Ruskin initially shared a professional relationship, with Ruskin supporting the Pre-Raphaelite movement. They became closer when Millais accompanied Ruskin and his wife Effie on a trip to Scotland in 1853.

During this trip, Millais fell in love with Effie while painting Ruskin’s portrait. The situation grew complicated when Effie’s marriage to Ruskin was annulled on grounds of non-consummation.

Millais married Effie in 1855, creating a scandal in Victorian society. The relationship with Ruskin deteriorated, though Ruskin continued to acknowledge Millais’ talent even while criticizing his later commercial success.

What role did Millais play in the Victorian art scene?

Millais achieved remarkable commercial and critical success in Victorian England. He received numerous commissions from wealthy patrons and became one of the most financially successful artists of his time.

In 1885, he was made a baronet, the first artist to receive this honor. His election as President of the Royal Academy in 1896 confirmed his establishment status, though he died shortly after taking the position.

His accessible style and choice of sentimental subjects helped popularize art among middle-class Victorians. His images appeared on products and advertisements, bringing fine art into everyday homes.

How has Millais’ work been received and critiqued by contemporary art scholars?

Modern scholars recognize Millais’ technical brilliance. They also note the contrast between his early and late work. His Pre-Raphaelite paintings are widely studied for their symbolic depth and technical innovation.

Some critics view his later commercial success as artistic compromise. Others argue his evolution reflects adaptability and understanding of changing public tastes.

Recent exhibitions have sparked renewed interest in Millais’ full career. Scholars now appreciate both his radical early contributions and his later role in shaping Victorian visual culture.