George Grosz Painter: A Pioneer of Weimar-Era Satirical Art

Born: July 26, 1893, Berlin, Kingdom of Prussia, German Empire

Death: July 6, 1959, West Berlin, West Germany

Art Movement: Dada, Expressionism, New Objectivity

Nationality: German, American

Teachers: Richard Müller, Robert Sterl, Raphael Wehle, Osmar Schindler, and Emil Orlik

Institution: Dresden Academy of Fine Arts and Berlin College of Arts and Crafts

George Grosz Painter: A Pioneer of Weimar-Era Satirical Art

George Grosz Biography

George Grosz was a prominent German artist known for his scathing caricatures and paintings that critiqued German society. His work captured the chaos and corruption of the Weimar Republic period, making him one of the most important artists of the early 20th century.

Early Life and Education

George Grosz was born Georg Ehrenfried Groß on July 26, 1893, in Berlin, Germany. He grew up in the small town of Stolp (now Słupsk, Poland) where his father ran a local inn.

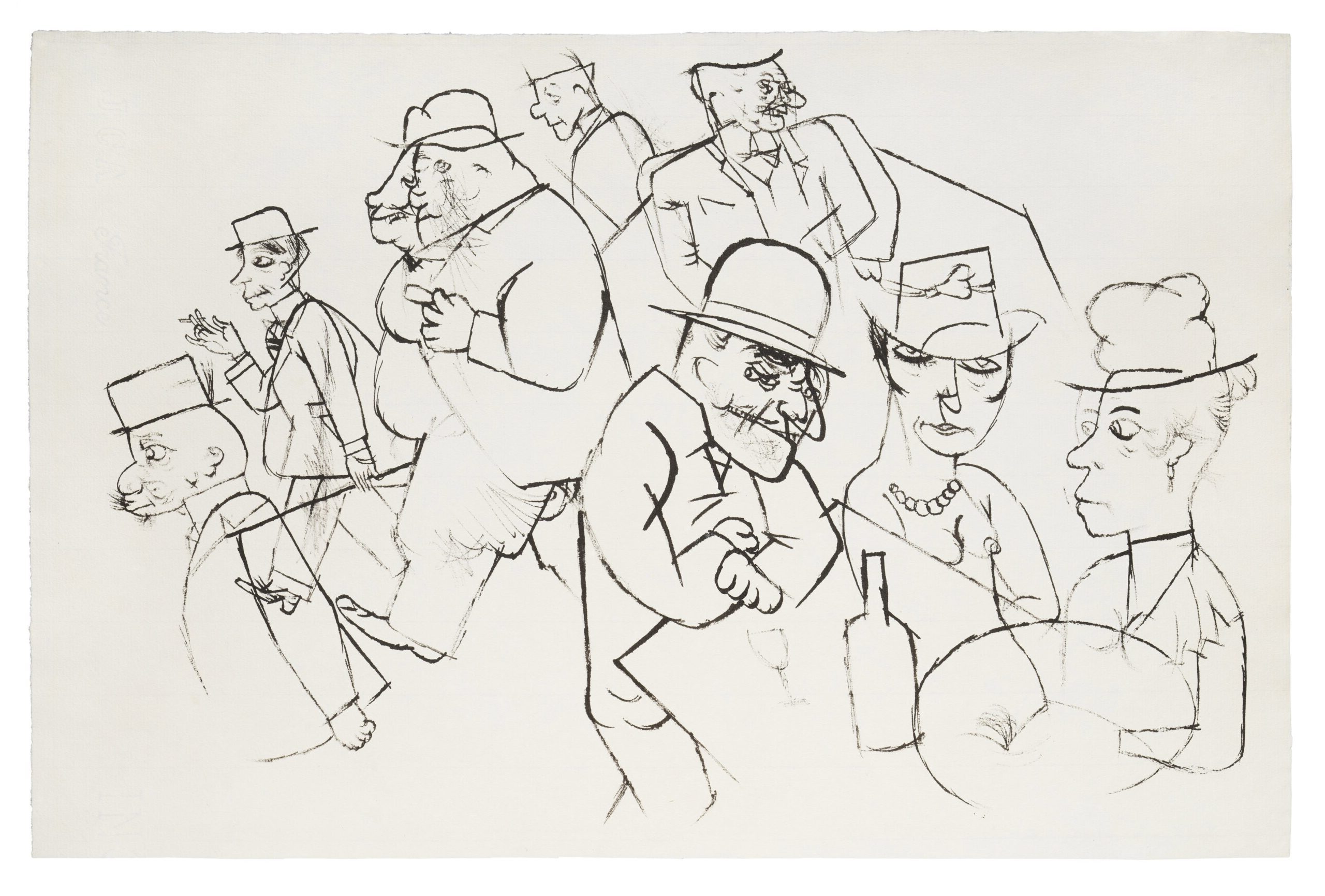

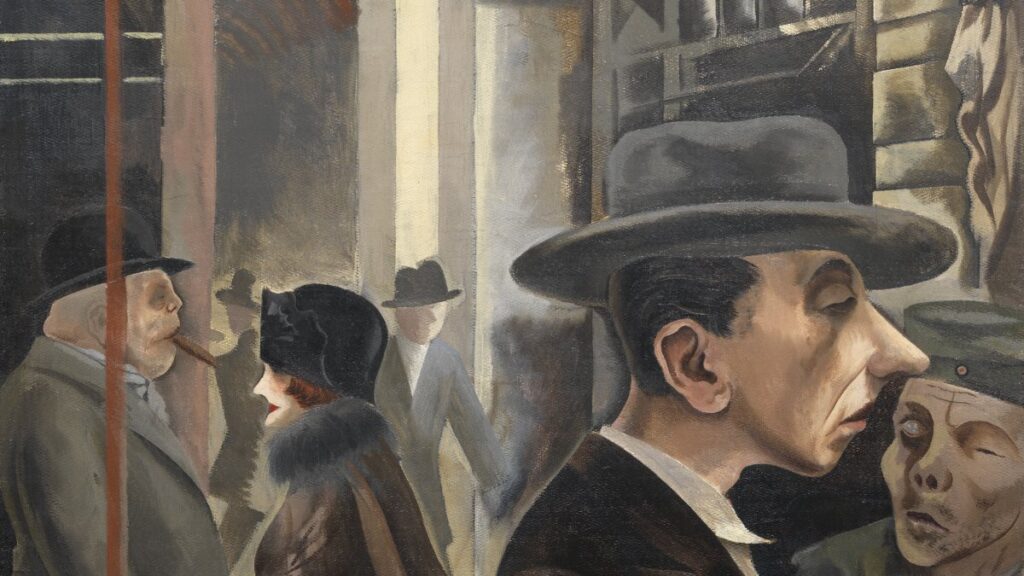

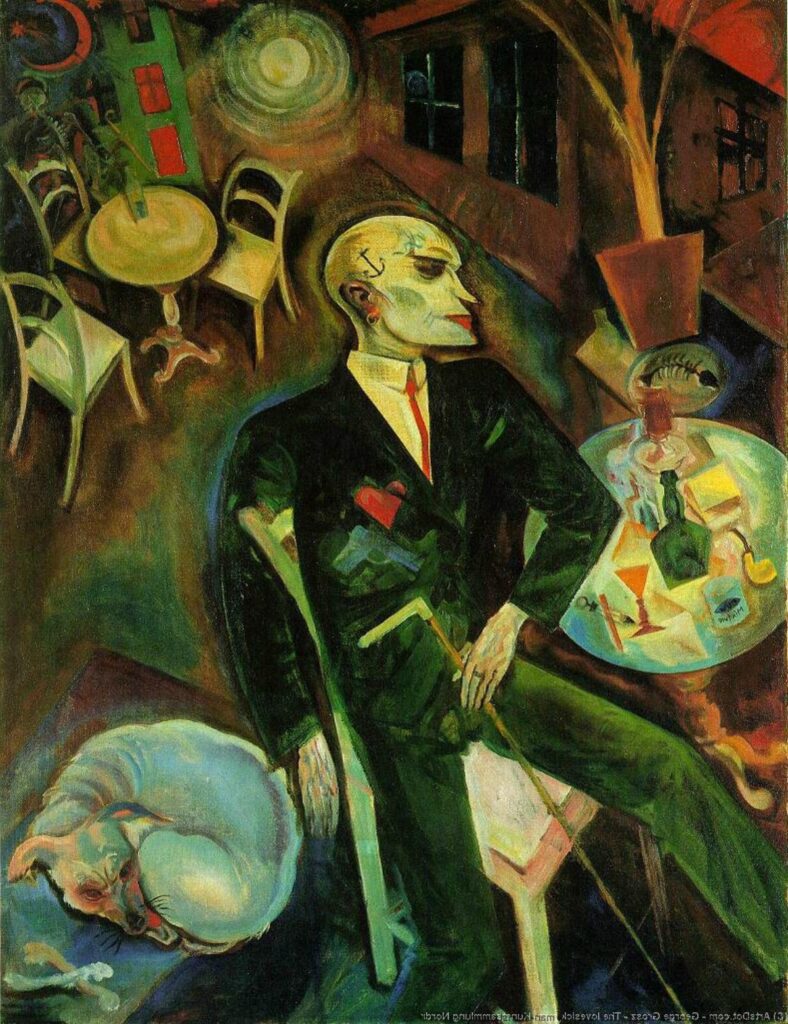

Street Scene (Kurfürstendamm) (1925) by George Grosz

Young Grosz showed artistic talent early on. He began his formal art education at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts in 1909.

He later studied at the Berlin College of Arts and Crafts and the Berlin Academy of Arts. These institutions provided him with traditional training, though he would eventually reject many academic conventions.

During these formative years, Grosz admired artists like Rembrandt and Renaissance masters. His early drawings showed remarkable technical skill and attention to detail.

Career and Artistic Development

Grosz’s military service during World War I deeply affected his artistic outlook. After being discharged in 1915, his work turned sharply critical of German militarism and society.

He joined the Berlin Dada movement in 1918, embracing its anti-establishment philosophy. This period marked his development of a harsh, angular style perfect for social critique.

His most famous works emerged in the 1920s. “Ecce Homo” (1923) and “The Face of the Ruling Class” (1921) featured biting caricatures of corrupt politicians, greedy businessmen, and disabled war veterans.

Grosz became associated with the New Objectivity movement. His precise, unflinching style depicted the moral decay he perceived in post-war German society.

By the mid-1920s, Grosz was internationally recognized. His illustrations appeared in left-wing publications, and his paintings were exhibited throughout Europe.

Political Engagement and Exile

Grosz joined the Communist Party of Germany in 1919 but left in 1923, disillusioned with its practices. Nevertheless, his art remained politically charged.

His unflattering portrayals of military officers, clergy, and industrialists led to multiple legal battles. He faced charges of “insulting the army” and blasphemy throughout the 1920s.

As the Nazi party gained power, Grosz became a primary target. His anti-militaristic views and unflattering depictions of German society were considered “degenerate” by Nazi standards.

In 1933, with Hitler’s rise to power, Grosz wisely fled to the United States. The Nazis later confiscated and destroyed much of his work left behind in Germany.

He became an American citizen in 1938, leaving behind the political turmoil that had fueled his most powerful work.

Later Years and Death

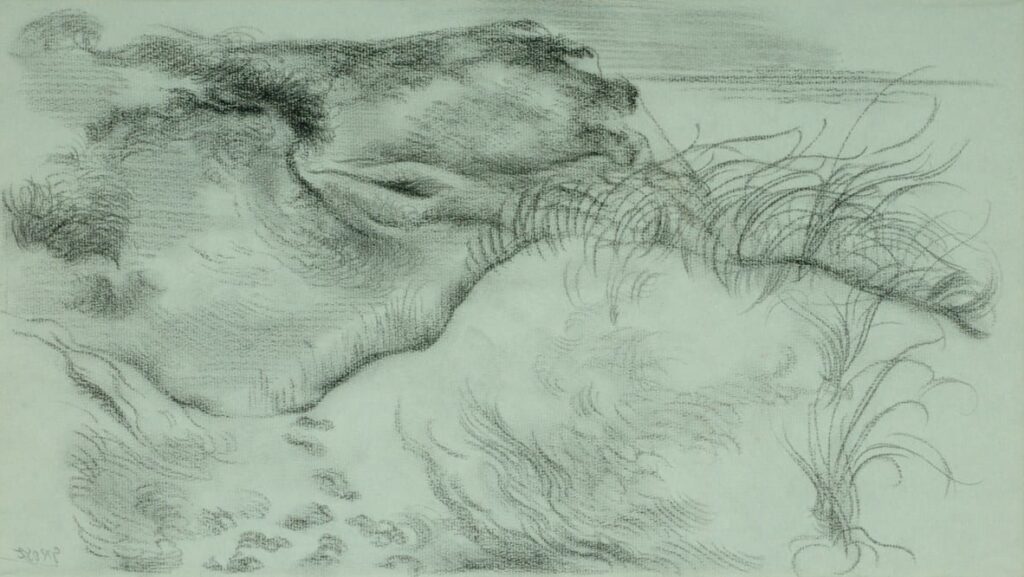

In America, Grosz taught at the Art Students League of New York. His new surroundings and relative safety changed the tone of his work.

His American paintings lacked the biting social criticism of his German period. He focused more on landscapes and traditional subjects, though he did create some anti-war works during World War II.

Grosz struggled with alcoholism and depression in his later years. The fire that had fueled his earlier work seemed diminished in the American context.

In 1959, he returned to Berlin for a visit. On July 6, 1959, shortly after arriving back in Germany, he died after falling down stairs following a night of drinking. He was 65 years old.

His legacy lives on through his remarkable body of work that documents a critical period in German history. The Museum of Modern Art and other major institutions preserve his powerful visual commentary on war, corruption, and social injustice.

Artistic Style and Influence

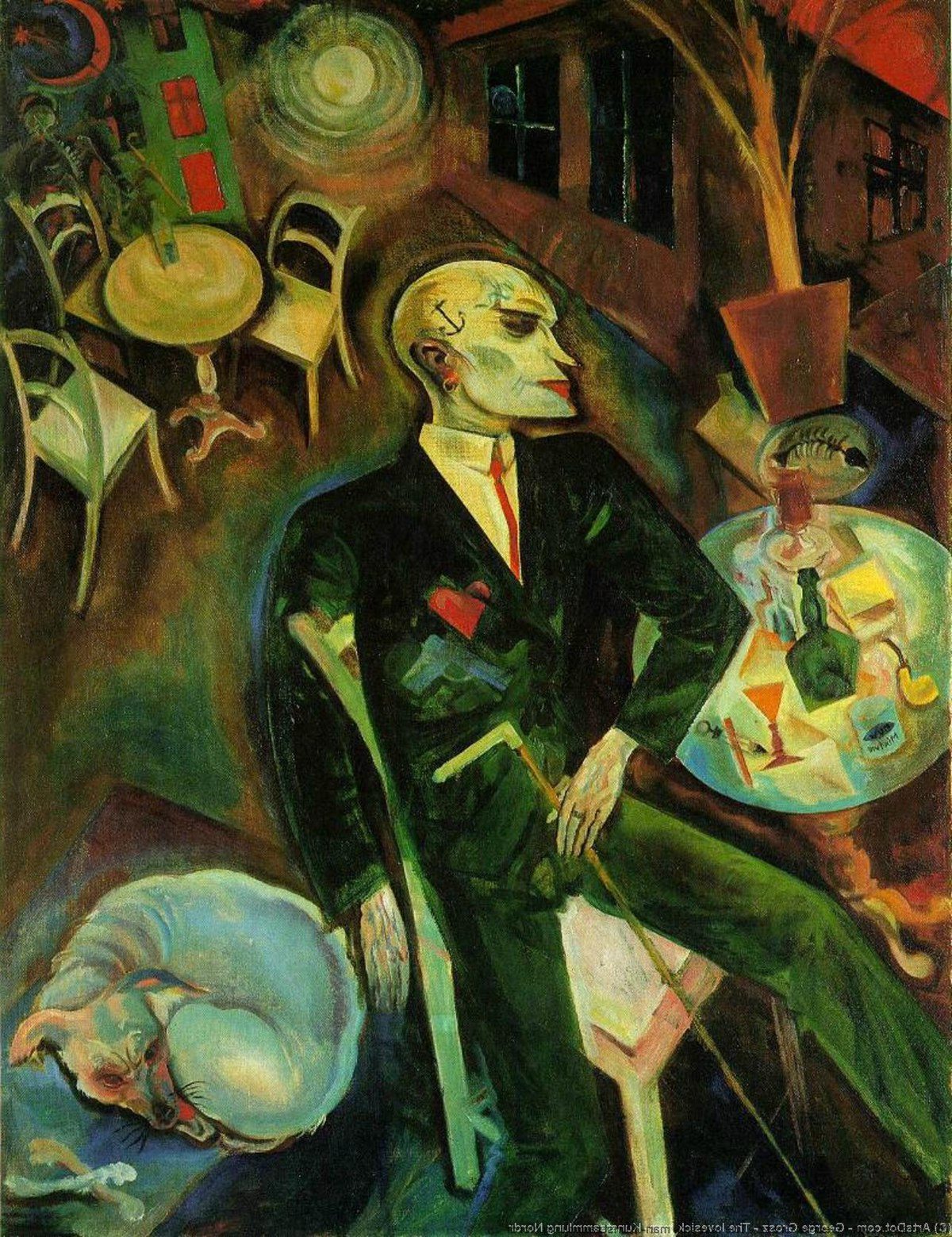

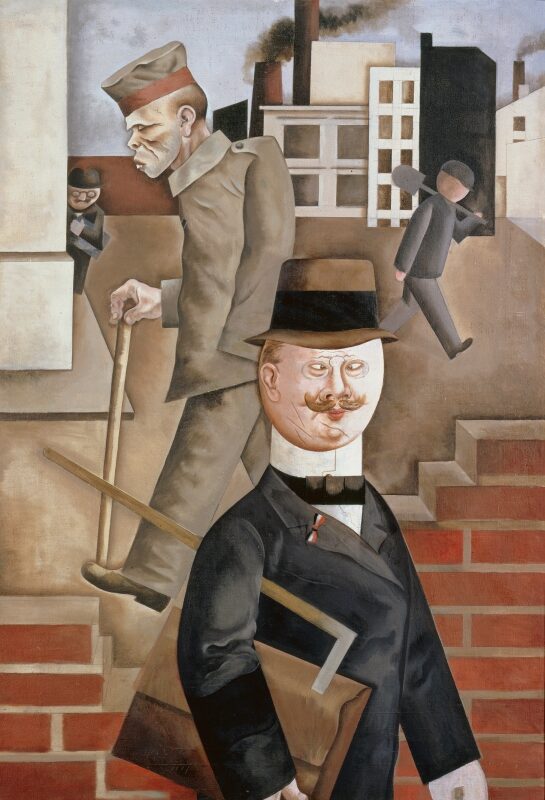

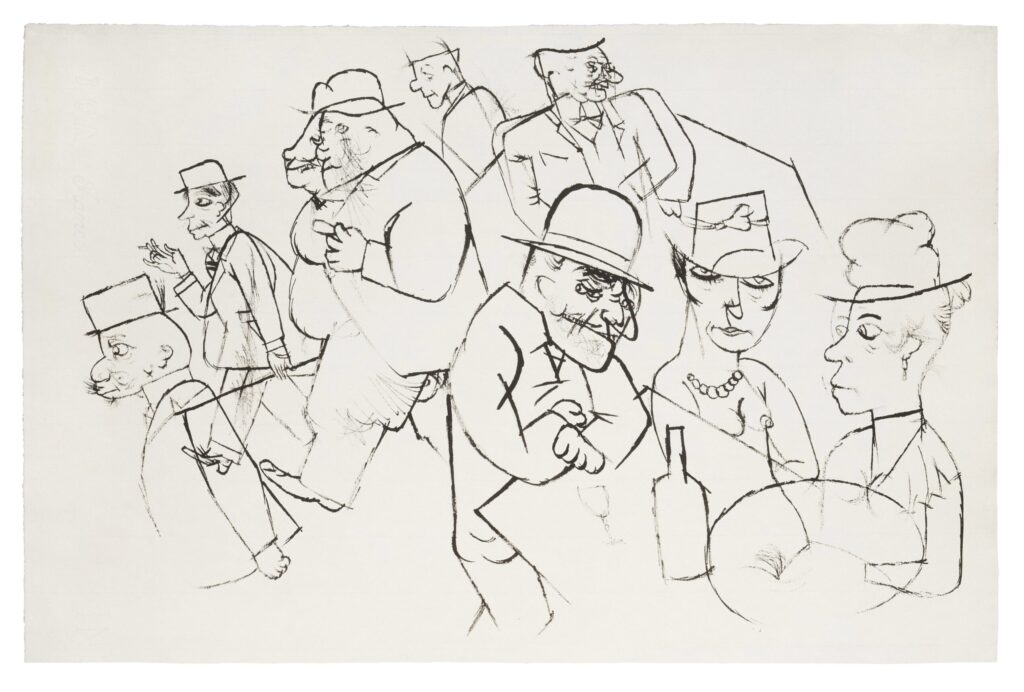

Schönheitsabend in der Motzstrasse, 1918, by George Grosz

George Grosz developed a distinctive artistic approach that captured the corruption and decadence of German society during the Weimar Republic. His sharp visual commentary combined technical precision with biting social criticism, establishing him as one of the most significant artists of 20th century Germany.

Dada and New Objectivity Movements

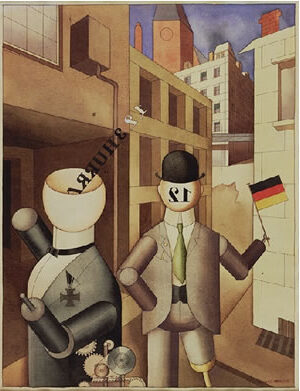

Grosz became a founding member of Berlin Dada around 1917, embracing its anti-establishment philosophy during the chaos of World War I. His Dadaist works featured photomontage and collage techniques that deliberately disrupted conventional artistic standards.

By the early 1920s, Grosz shifted toward New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit), a movement rejecting expressionism in favor of unsentimental realism. This transition allowed him to develop his signature style: precise linework combined with caustic social observation.

Unlike some contemporaries, Grosz maintained his political edge within New Objectivity. His work exemplified the movement’s “verist” wing, which used realistic portrayals to expose social truths rather than idealize them.

Satirical Portrayals and Social Criticism

Grosz’s art mercilessly depicted Germany’s post-WWI society, particularly targeting the military, clergy, and bourgeoisie. His caricatures featured bloated industrialists, corrupt officials, and maimed veterans coexisting in chaotic urban scenes.

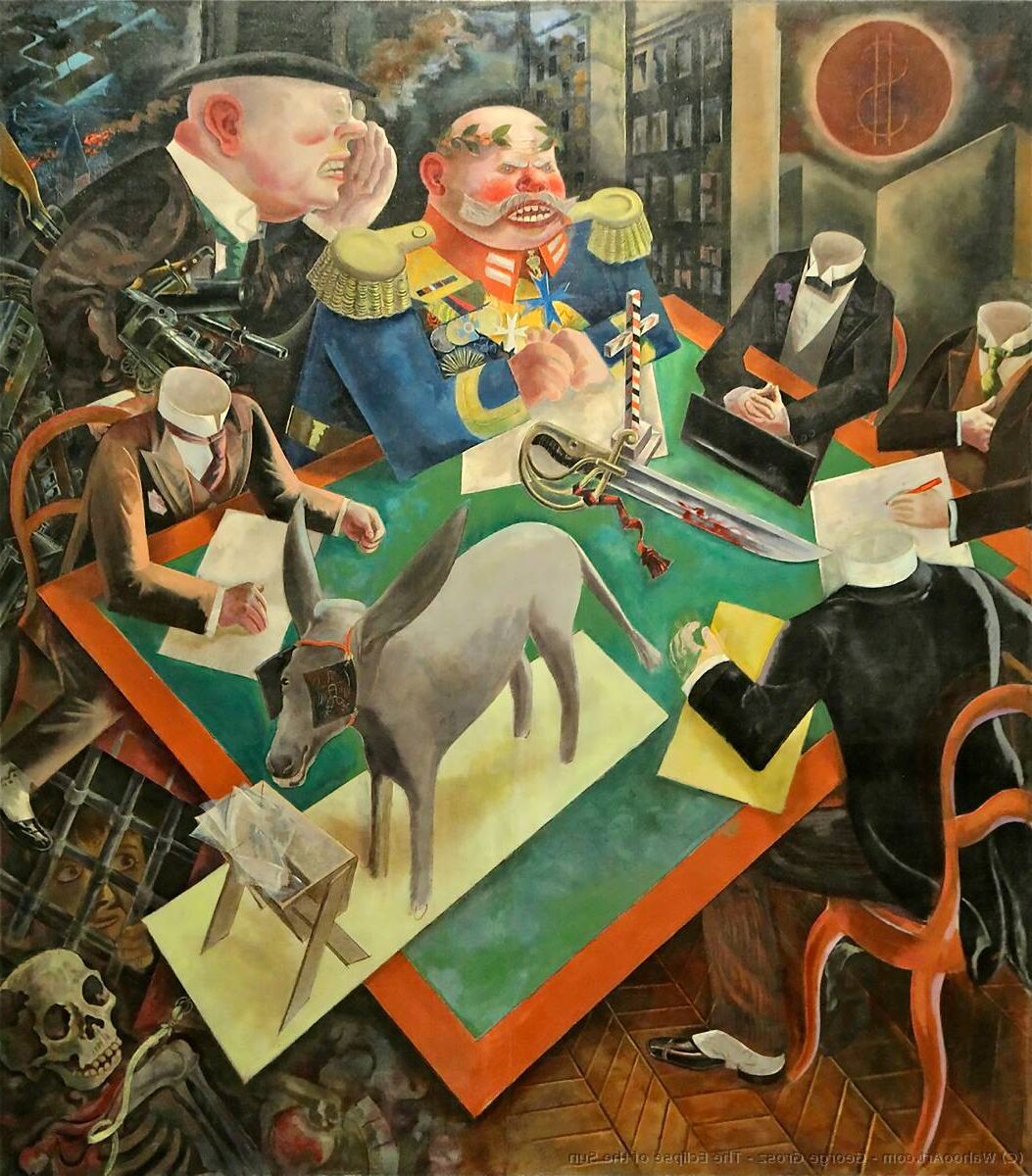

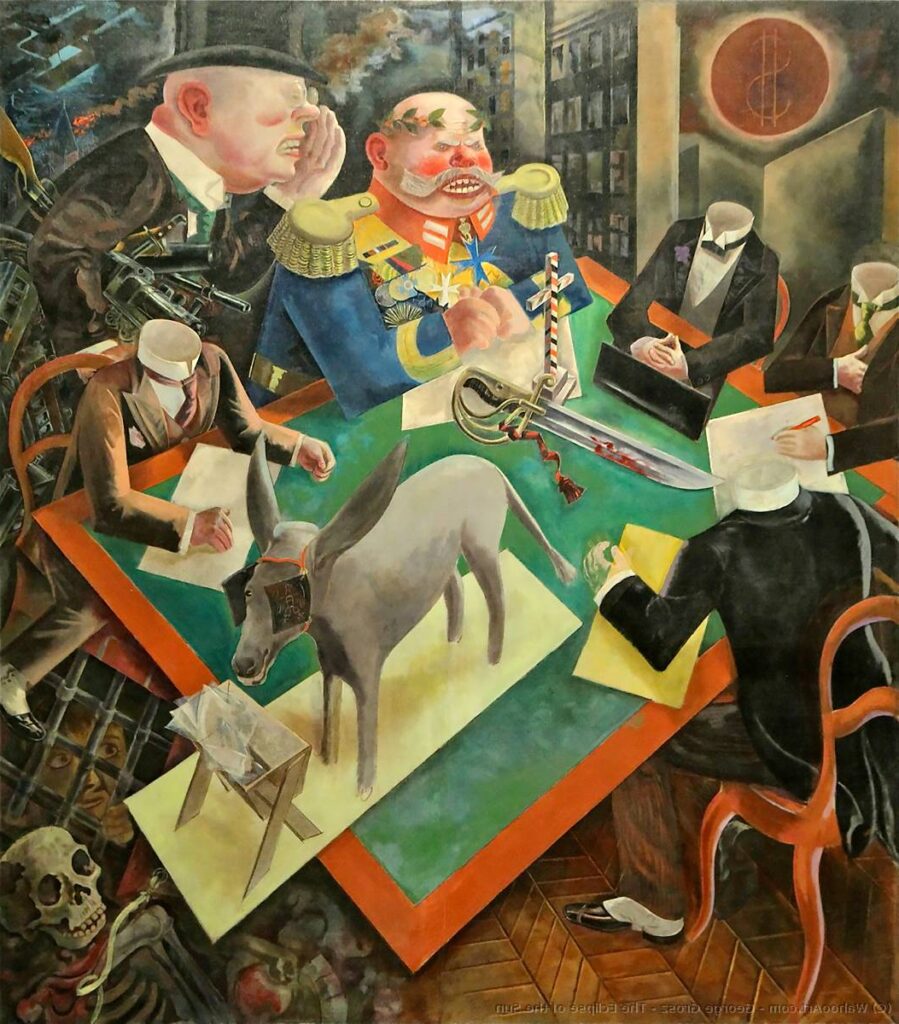

Works like “The Pillars of Society” (1926) revealed hypocrisy among Germany’s elite through exaggerated features and grotesque symbolism. Grosz portrayed his subjects with physical deformities that reflected their moral corruption.

His satirical approach drew from journalistic illustration and caricature traditions. Despite facing censorship and legal troubles for his provocative images, Grosz refused to soften his critique of German society during the rise of fascism.

Techniques and Mediums Employed

Grosz mastered several techniques that enhanced his social commentary. His pen and ink drawings displayed remarkable precision with clean, sharp lines that defined forms with minimal strokes.

Watercolor washes often accompanied his linework, adding psychological depth through selective color. This combination created a signature look—detailed drawings enhanced by strategic color application to highlight decadence or violence.

In his paintings, Grosz employed a meticulous approach with thin layers of oil paint. His palette typically featured acidic greens, harsh reds, and murky browns that intensified the unsettling quality of his scenes.

Grosz also pioneered new approaches to printmaking. His lithographs and portfolios like “The Face of the Ruling Class” (1921) democratized his art by making it accessible to wider audiences through mass production.

Legacy and Notable Works

George Grosz left an indelible mark on 20th-century art through his biting satirical works and unflinching social criticism. His distinctive style influenced generations of artists and continues to resonate in contemporary political art.

Impact on Modern Art

Grosz pioneered a raw, uncompromising approach to social critique that transformed modern art. His blend of Dadaism and New Objectivity challenged artistic conventions and expanded the boundaries of political expression through visual media.

Many contemporary artists cite Grosz as a major influence, particularly those who use art as social commentary. His willingness to confront political corruption and social hypocrisy created a blueprint for engaged artistic practice.

The Grosz technique of exaggeration and caricature to reveal uncomfortable truths has become a fundamental strategy in political art. His work demonstrated that art could be both aesthetically innovative and politically potent.

Prominent Pieces

“The Pillars of Society” (1926) stands as one of Grosz’s most iconic works. This painting brutally satirizes the corrupt power structures of Weimar Germany through grotesque caricatures of military officers, politicians, and journalists.

“Eclipse of the Sun” (1926) depicts fat industrialists controlling puppet politicians while ordinary citizens suffer. The striking composition and biting commentary make it a centerpiece of his oeuvre.

“Metropolis” (1916-1917) captures the chaotic energy and moral decay of Berlin through fragmented scenes of urban life. Its dynamic style reflects both Futurist and Expressionist influences.

His portfolio “The Face of the Ruling Class” (1921) contains 55 lithographs that offer scathing portraits of Germany’s elite.

Exhibitions and Collections

Major museums worldwide house Grosz’s works, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York, which holds an extensive collection of his drawings and paintings. The Neue Nationalgalerie in Berlin features significant Grosz pieces in its permanent collection.

Dunes Cape Cod, 1939, by George Grosz

Retrospectives of Grosz’s work continue to draw attention. The 2013 exhibition “George Grosz: The Years in America” at the New York Historical Society highlighted his later career and ongoing relevance.

The George Grosz Archive at the Academy of Arts in Berlin preserves over 1,500 original works, sketches, and personal documents. This collection serves as an invaluable resource for scholars studying his artistic development and political views.

Frequently Asked Questions

George Grosz remains one of the most influential painters of the 20th century, known for his scathing social critiques and distinctive style. His life experiences and artistic choices continue to spark curiosity among art enthusiasts worldwide.

What are the major themes found in George Grosz’s artworks?

George Grosz’s art centered on sharp social criticism and political commentary. He focused on exposing the corruption, greed, and hypocrisy of German society during the Weimar Republic.

His paintings often depicted war profiteers, politicians, and military figures as grotesque caricatures. The theme of moral decay appears consistently across his work.

Grosz also highlighted class inequality, showing stark contrasts between the wealthy elite and struggling working classes. Violence, both physical and systemic, features prominently in many of his most famous works.

How did George Grosz’s experience in World War I influence his painting style?

Grosz’s military service during World War I profoundly shaped his artistic vision. After being discharged for medical reasons, he developed a deep antipathy toward militarism that permeated his work.

The war’s brutality led him to adopt harsh, angular lines and distorted figures that conveyed psychological trauma. His firsthand experience with violence made his anti-war stance more personal and visceral.

The chaotic aftermath of war in Germany provided Grosz with scenes of social breakdown that became central to his paintings. His style became more aggressive and confrontational, reflecting his disillusionment with humanity.

What was George Grosz’s role in the Dada art movement?

Grosz became a founding member of Berlin Dada in 1918, helping establish its politically charged direction. Unlike other Dada centers, Berlin Dada focused on political critique rather than purely aesthetic concerns.

He contributed provocative photomontages and satirical drawings to Dada publications. His work embodied the movement’s rejection of traditional artistic values and embrace of chaotic, fragmented imagery.

Grosz collaborated with fellow Dadaists on exhibitions and publications that challenged bourgeois sensibilities. His influence helped shape Dada as a vehicle for social and political commentary rather than just artistic experimentation.

Can you describe the techniques and mediums George Grosz preferred in his paintings?

Grosz worked primarily with oil paints, watercolors, and ink drawings. His draftsmanship was exceptional, allowing him to create detailed caricatures with minimal lines.

He developed a technique of sharp, angular contours that defined his figures with clinical precision. Grosz often employed flat areas of color with limited shading to create stark, poster-like images.

His watercolor technique featured loose washes combined with precise line work. In many works, he deliberately used crude or unrefined brushwork to convey a sense of urgency and rawness.

How did George Grosz’s work comment on society and politics of his time?

Grosz functioned as a visual journalist, documenting the moral and political decay of interwar Germany. His paintings exposed the corruption of government officials, businessmen, and military officers with unflinching clarity.

He portrayed the rising threat of Nazism through caricatures that revealed its violent and dehumanizing nature. Grosz’s work highlighted the hypocrisies of those who preached patriotism while profiting from war and suffering.

His street scenes depicted the harsh realities of urban life, including prostitution, poverty, and violence. Grosz refused to romanticize any aspect of society, presenting even ordinary citizens as complicit in systemic problems.

What was the impact of George Grosz’s art on future artistic movements and expressions?

Grosz’s art influenced generations of political artists and illustrators. His combination of realism and caricature created a template for effective visual political commentary.

The New Objectivity movement in Germany drew directly from his unflinching depictions of social reality. His work also prefigured aspects of Pop Art in its use of bold imagery and cultural criticism.

Grosz’s legacy extends to contemporary political cartoonists and street artists who use similar visual strategies. His techniques for depicting power and corruption remain relevant in modern political art.