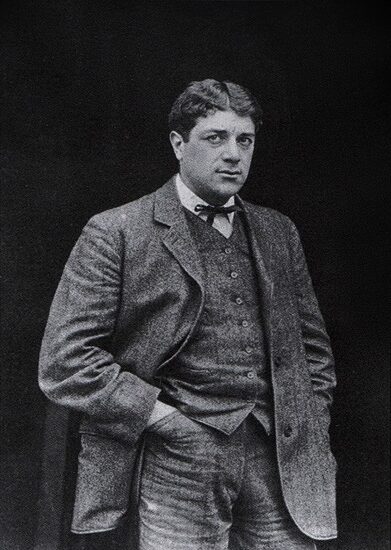

Georges Braque Painter: Pioneer of Cubism and Modern Art Innovator

Born: 13 May 1882, Val-d’Oise, France

Death: 31 August 1963, Paris, France

Art Movement: Cubism, Fauvism

Nationality: French

Influenced By: Paul Cézanne

Institution: École supérieure d’art et design Le Havre-Rouen and Académie Humbert

Georges Braque Painter: Pioneer of Cubism and Modern Art Innovator

Life and Career of Georges Braque

Georges Braque (1882-1963) transformed modern art through his pioneering work in Cubism alongside Pablo Picasso. His artistic journey spanned multiple influential movements, from Fauvism to his later more personal style, establishing him as one of the most important painters of the 20th century.

Early Life and Education

Georges Braque was born on May 13, 1882, in Argenteuil, France. He grew up in Le Havre, where his father ran a painting business. This early exposure to decorative painting techniques would later influence his artistic approach.

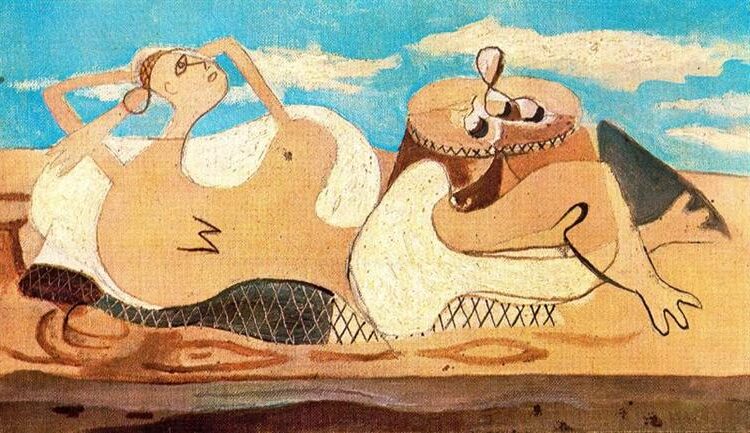

Nude Reclining on the Pedestal, 1931 by Georges Braque

Braque began his formal training at the École des Beaux-Arts in Le Havre from 1897 to 1899. He then moved to Paris around 1900 to study at the Académie Humbert.

His early work showed influences of Impressionism. During this period, he completed his military service from 1901 to 1902. Upon returning to Paris, Braque focused fully on his artistic development.

The young artist made connections in Parisian artistic circles that would prove crucial to his development. His technical foundation in decorative painting gave him a unique perspective on color and form.

Fauvism Period

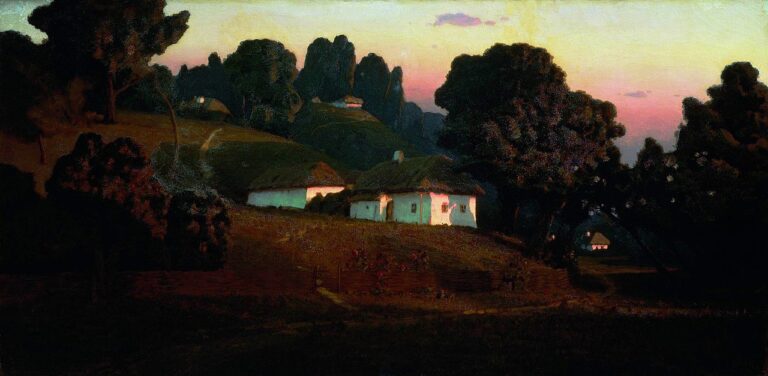

Braque embraced Fauvism around 1905 after seeing work by Henri Matisse and André Derain. This bold style used vibrant, non-naturalistic colors and simplified forms.

His Fauvist landscapes of L’Estaque, a fishing village near Marseille, featured bright colors and expressive brushwork. Works like “Houses at l’Estaque” (1906) demonstrate his mastery of this style.

In 1907, Braque exhibited his Fauvist paintings at the Salon des Indépendants. Critics noted his distinctive approach even within this revolutionary movement.

His Fauvist period was brief but productive. The bold use of color and simplified forms during this time prepared him for his next artistic breakthrough.

Braque’s friendship with Picasso began around this time, setting the stage for their historic collaboration. Their mutual interest in formal experimentation would soon transform art history.

Invention of Cubism

In 1907, Braque visited Picasso’s studio and saw “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon,” a painting that shocked him with its radical approach. This encounter marked a turning point in his artistic direction.

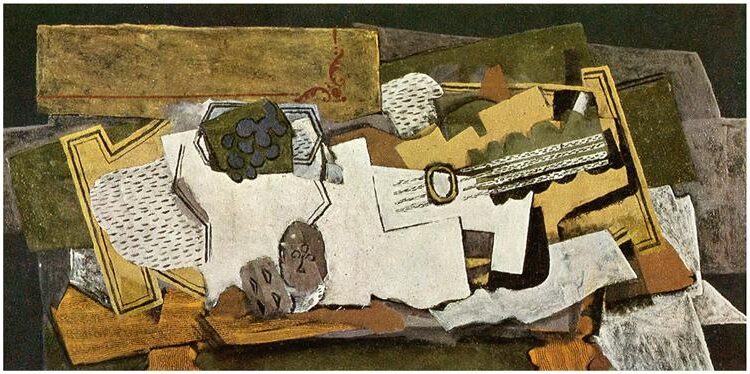

Still Life with a Guitar, 1919 by Georges Braque

Between 1908 and 1914, Braque and Picasso worked so closely that they referred to themselves as “two mountaineers roped together.” Their collaboration developed Cubism through careful analysis and reconstruction of forms.

Braque’s “Houses at l’Estaque” (1908) prompted critic Louis Vauxcelles to describe the paintings as made of “little cubes,” giving the movement its name. This work showed his shift toward geometric simplification.

The artists developed Analytical Cubism, breaking objects into faceted planes. Later, they invented Synthetic Cubism, incorporating collage elements and actual materials like newspaper.

Braque pioneered the papier collé technique in 1912, gluing printed paper into his compositions. This innovation expanded artistic possibilities beyond traditional painting methods.

World War I Service

Braque enlisted in the French Army in 1914 when World War I broke out. This decision temporarily halted his artistic collaboration with Picasso.

In 1915, he suffered a severe head wound at the Battle of Carency. The injury required trepanation (skull surgery) and a long recovery period. Braque temporarily lost his sight and experienced temporary paralysis.

He couldn’t return to painting until 1917. This interruption marked the end of his close partnership with Picasso, as their artistic paths began to diverge after the war.

The war experience profoundly affected Braque’s outlook and artistic approach. His post-war work would show more personal expression and a renewed interest in color and texture.

Despite the trauma, Braque maintained his commitment to Cubist principles throughout his recovery. His war service earned him the Croix de Guerre and French citizenship.

Post-War Artistic Developments

After recovering, Braque developed a more personal style while maintaining Cubist elements. His post-war works featured softer forms and richer textures than his pre-war paintings.

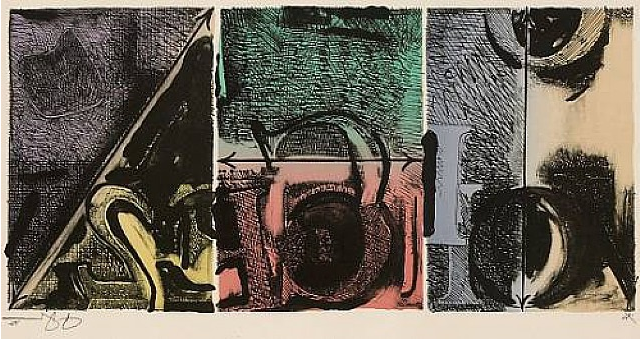

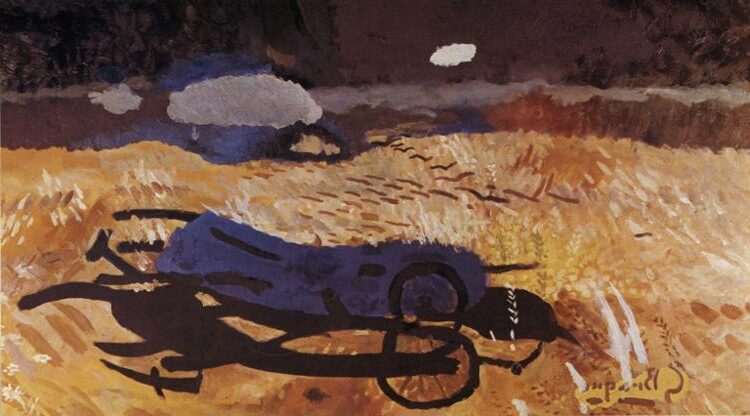

The Weeding Machine, 1961 by Georges Braque

During the 1920s, he created still-life paintings with musical instruments, fruit, and tabletop objects. These works combined Cubist structure with more naturalistic elements and vibrant colors.

In the 1930s, Braque began his famous “Interiors” series, depicting domestic spaces with complex patterns. He also created the “Bird” series, which continued into the 1950s, featuring stylized birds in flight.

Braque received growing recognition, including a solo exhibition at the Louvre in 1961—an honor rarely given to living artists. He continued working despite declining health in his later years.

He died on August 31, 1963, in Paris. Throughout his career, Braque maintained his artistic integrity and innovative spirit, leaving behind a body of work that transformed modern art.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Georges Braque developed distinctive artistic approaches that revolutionized modern art. His innovative techniques and theoretical contributions shaped Cubism and influenced generations of artists who followed.

Cubist Theories and Collaboration with Picasso

Braque’s partnership with Pablo Picasso between 1908 and 1914 produced Analytical Cubism, a radical departure from traditional representation. They worked so closely that they often couldn’t identify which artist created which painting.

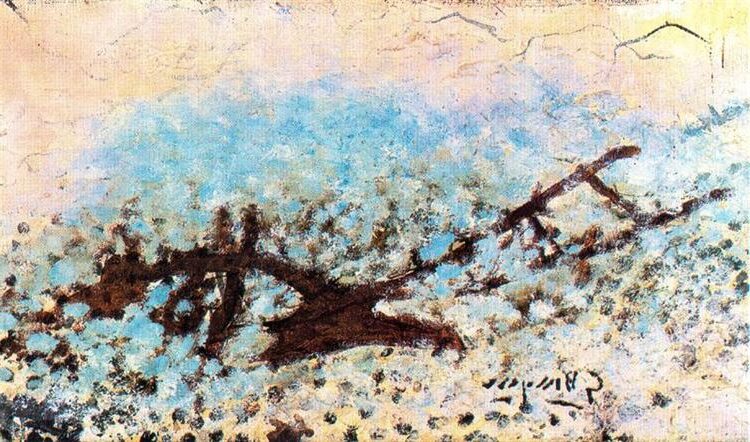

The Plow, 1961 by Georges Braque

Their method involved breaking objects into geometric shapes and presenting multiple viewpoints simultaneously. Braque once explained, “The aim is not to reconstitute an anecdotal fact, but to constitute a pictorial fact.”

Unlike earlier movements, Braque and Picasso rejected the single point perspective that had dominated Western art since the Renaissance. Instead, they created flattened, fragmented compositions that revealed objects from several angles at once.

Braque particularly contributed the concept of “passage” – the technique of merging foreground and background through overlapping planes – which became central to Cubist theory.

Use of Color and Texture

Braque employed a restrained color palette during his Cubist period, focusing on browns, grays, and muted tones. This deliberate limitation helped emphasize structural elements rather than decorative aspects.

His textural techniques were revolutionary. Braque developed “faux bois” (false wood) and other decorative painting methods that simulated materials like marble, wood grain, and wallpaper.

He applied paint in varied ways – sometimes thin and transparent, sometimes thick and textured. Braque often used a comb to create linear patterns in wet paint.

After 1912, his palette gradually expanded to include brighter colors, particularly during his transition to Synthetic Cubism. His unique approach to texture created tactile surfaces that invited viewers to consider the physical reality of the painted surface.

Pioneering Collage

In 1912, Braque invented papier collé (pasted paper), a groundbreaking technique that transformed modern art. He first incorporated foreign elements – newspaper clippings, wallpaper, and imitation wood grain paper – into his “Fruit Dish and Glass” composition.

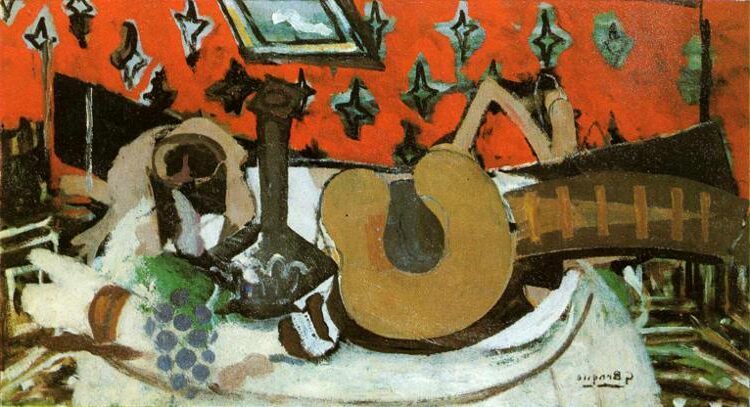

Still Life Mandolin II, c.1939 – Georges Braque

This innovation allowed Braque to:

- Create textural contrasts between painted and non-painted surfaces

- Introduce reality directly into abstract compositions

- Play with relationships between representation and actual objects

Collage challenged fundamental ideas about art by incorporating everyday materials into “high art.” It blurred boundaries between representation and reality, allowing objects to exist both as themselves and as artistic elements.

Braque’s collage techniques influenced Dada, Surrealism, and countless movements that followed. His revolutionary approach freed artists to explore new materials and methods of construction.

Later Works and Styles

After World War I, Braque moved away from strict Cubism toward a more personal style. His work retained geometric elements but became more colorful and rhythmic.

During the 1920s, he created the “Canephora” series featuring classical female figures. These works blended Cubist fragmentation with more traditional representation.

The 1930s brought Braque’s “Interiors” – intimate domestic scenes with flattened perspective and layered patterns. In these works, he explored the poetry of everyday objects through still lifes of tables, chairs, and household items.

His final period featured the acclaimed “Bird” series, where simplified bird forms soared through abstract spaces. These works combined decorative elements with profound symbolic meaning.

Throughout his career, Braque maintained exceptional craftsmanship. He mixed his own pigments and carefully prepared surfaces to achieve precise visual effects.

Impact and Legacy

Georges Braque’s contributions to art history extend far beyond his lifetime. His innovative approach to form, space, and perspective transformed modern art and influenced countless artists across generations.

Influence on Modern Art

Braque’s pioneering work with Cubism fundamentally changed how artists approached representation. Together with Picasso, he challenged the traditional single-viewpoint perspective that had dominated Western art for centuries. This revolutionary approach influenced nearly every major art movement that followed, including Futurism, Constructivism, and Abstract Expressionism.

Still Life with Fruits, c. 1925 by Georges Braque

Many artists adopted Braque’s techniques of fragmentation and multiple perspectives. His textured surfaces and collage innovations became standard practices in modern art.

Braque’s methodical, thoughtful approach contrasted with Picasso’s more impulsive style, providing artists with different models for developing Cubist principles. His influence can be seen in the work of artists like Juan Gris, Fernand Léger, and even later figures such as Richard Diebenkorn.

Major Works and Exhibitions

Braque’s most significant works include his early Fauve landscapes and his groundbreaking Cubist paintings. Key examples include:

- Houses at l’Estaque (1908) – sparked critic Louis Vauxcelles to coin the term “Cubism”

- Violin and Palette (1909) – demonstrated his analytical Cubist approach

- Fruit Dish and Glass (1912) – pioneered the papier collé technique

- The Portuguese (1911) – exemplifies mature Analytical Cubism

His work has been featured in major retrospectives at prestigious institutions worldwide. The Museum of Modern Art in New York held significant exhibitions of his work in 1949 and 1989.

The Pompidou Center in Paris organized a comprehensive retrospective in 2013, bringing renewed attention to Braque’s contributions beyond Cubism.

Recognition and Awards

Braque received numerous honors during his lifetime. The French government awarded him the Legion of Honor in 1951, recognizing his contributions to French culture and art.

In 1961, Braque became the first living artist to have work exhibited at the Louvre. This unprecedented honor highlighted his significance in art history.

He won the Carnegie Prize in 1937 for his painting “The Yellow Tablecloth.” Critics and art historians increasingly recognized his equal role with Picasso in developing Cubism.

After his death in 1963, Braque’s legacy was further cemented through retrospectives, scholarly studies, and the increasing value of his works. His studio practices and philosophical approach to art continue to inspire contemporary artists.

Frequently Asked Questions

Georges Braque’s artistic journey and contributions to modern art often spark curiosity among art enthusiasts. His pioneering work, collaborations, and evolution as an artist shaped significant movements in 20th-century art.

What artistic movement is Georges Braque best known for co-founding?

Georges Braque is best known for co-founding Cubism alongside Pablo Picasso. This revolutionary art movement emerged around 1907-1908 and broke from traditional representation by depicting objects from multiple viewpoints simultaneously.

Cubism fundamentally changed how artists approached space and form in painting. Braque’s early Cubist works, like “Houses at l’Estaque” (1908), helped establish the movement’s distinctive style.

The movement is typically divided into two phases: Analytical Cubism and Synthetic Cubism. Braque made significant contributions to both periods.

How did Georges Braque’s style evolve throughout his career?

Braque began as a Fauvist, using bright colors and bold brushstrokes in works like “Landscape at La Ciotat” (1907). His style shifted dramatically when he encountered Picasso and began exploring Cubist ideas.

During his Cubist period, he moved from Analytical Cubism’s fragmenting of objects to Synthetic Cubism’s incorporation of collage and mixed media. After World War I, his work became more colorful and decorative.

In his later years, Braque developed a more personal style featuring birds, landscapes, and studio interiors. These works displayed looser brushwork while maintaining his interest in space and form.

Can you detail the collaboration between Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso?

Braque and Picasso collaborated intensely between 1908 and 1914, a partnership often described as one of art history‘s most productive. They worked so closely that they sometimes didn’t sign their paintings, making it difficult to distinguish their work.

Together they developed Analytical Cubism, reducing objects to geometric forms and multiple viewpoints. In 1912, they pioneered papier collé (pasted paper) techniques, introducing real-world materials into fine art.

Their collaboration ended when Braque enlisted for World War I in 1914. Though they remained friendly, they never worked together with the same intensity again.

What are some of the most iconic paintings created by Georges Braque?

“Violin and Palette” (1909) exemplifies Braque’s Analytical Cubist period. The painting shows a fragmented, geometric approach to depicting a violin.

“Man with a Guitar” (1911) further developed these explorations of form and space.

“The Portuguese” (1911) is considered one of his masterpieces. The painting shows his skill at breaking down objects while maintaining recognizable elements.

“Fruit Dish and Glass” (1912) marked his transition to Synthetic Cubism.

Later works like “The Studio” series (1949-1956) showcase his mature style. These paintings combine elements of still life with more lyrical explorations of space and light.

How did World War I impact Georges Braque’s artwork and his approach to painting?

Braque suffered a severe head injury during World War I. This injury required a long recovery period.

This traumatic experience created a significant break in his artistic development and ended his close collaboration with Picasso.

When he resumed painting in 1917, his style had become more personal and reflective. His post-war work featured richer colors and textures, moving away from the austere palette of early Cubism.

The war experience led him to explore more tactile aspects of painting. He developed a meticulous approach that emphasized the physical properties of paint and surface.

What influence did Georges Braque have on later artists and art movements?

Braque’s innovations in Cubism profoundly influenced numerous movements. These include Futurism, Constructivism, and Abstract Expressionism. His collage techniques became fundamental to Dada and Surrealism.

His exploration of flattened space and multiple perspectives changed how artists approached representation. Later artists like Richard Diebenkorn cited Braque’s spatial compositions as important influences.

Braque’s methodical, thoughtful approach to art-making also influenced generations of painters. These painters valued craftsmanship and careful consideration of formal elements in their work.