Salvator Rosa: Painter of Dramatic Baroque Landscapes

Born: June 20 or July 21, 1615, Arenella, Kingdom of Naples

Death: March 15, 1673, Rome, Papal States

Art Movement: Baroque

Nationality: Italian

Teachers: Aniello Falcone, Francesco Fracanzano, and Paolo Greco

Salvator Rosa: Painter of Dramatic Baroque Landscapes

Life and Career

Salvator Rosa’s artistic journey spanned several Italian cities and evolved through distinct phases. His unconventional style and multifaceted talents made him one of the most distinctive figures in 17th-century Italian art.

Early Life in Naples

Born near Naples in 1615, Salvator Rosa began his artistic training under his brother-in-law Francesco Francanzano. Francanzano introduced him to the Neapolitan painting tradition. This early exposure shaped Rosa’s dramatic style and bold technique.

The Death of Regulus (c. 1650–1652) by Salvator Rosa

Rosa later studied with Aniello Falcone, known as the “oracle of battle scenes.” Falcone influenced his approach to action-filled compositions. During this period, he also absorbed the tenebrous style of Jusepe de Ribera, whose dramatic lighting and naturalistic depictions left a lasting impression.

The young artist struggled initially, selling small landscapes to local dealers. His early works already displayed the wild, romantic landscapes that would later become his trademark.

Roman Period and Artistic Development

Rosa moved to Rome in the late 1630s, where he quickly gained recognition for his unique landscape style and eccentric personality. Unlike many contemporaries, he refused to work on commission for patrons. Instead, he insisted on artistic freedom.

In Rome, Rosa expanded his repertoire beyond landscapes to include historical scenes, allegories, and philosophical subjects. His studio became a gathering place for intellectuals and artists.

During a four-year sojourn in Florence (1640-1644), Rosa found favor with the Medici court. There he founded the Accademia dei Percossi (“Academy of the Stricken”). At the academy, he showcased his talents not only as a painter but also as a poet, actor, and musician.

Final Years and Legacy

Rosa returned to Rome in 1649, where he remained until his death in 1673. During these productive later years, he refined his distinctive style characterized by wild, sublime landscapes with dramatic skies and tiny human figures.

Pythagoras Emerging from the Underworld (1662) by Salvator Rosa

His paintings became increasingly philosophical and sometimes satirical. Works from this period often feature bandits, soldiers, and hermits placed within turbulent landscapes, reflecting his interest in human frailty and mortality.

Rosa’s independent spirit and rejection of artistic conventions influenced later Romantic painters. His works featuring stormy scenes, ruins, and desolate landscapes with dramatic lighting established him as a forerunner of Romanticism.

As both an artist and intellectual, Rosa left behind a body of work that transcended the Baroque period. His paintings continue to be valued for their emotional intensity and innovative approach to landscape.

Artistic Style and Themes

Salvator Rosa developed a distinctive artistic approach that set him apart from his contemporaries. His work spans several genres and themes, showcasing his versatile talent and unique perspective on the world around him.

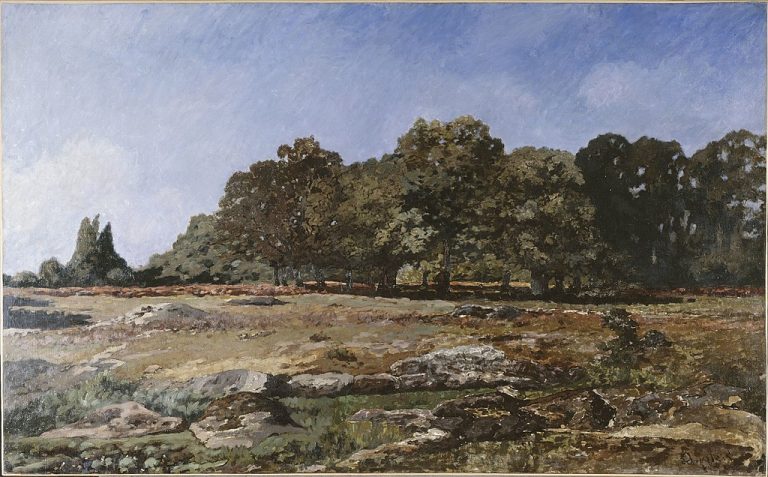

Landscapes and Nature

Rosa revolutionized landscape painting with his wild, untamed visions of nature. Unlike the serene pastoral scenes popular during his time, he depicted rugged, mountainous landscapes filled with jagged rocks, twisted trees, and ominous skies.

The Crucifixion of Polycrates the Tyrant after his Capture by the Persians (1662)

His landscapes often featured small human figures overwhelmed by the natural environment, emphasizing humanity’s vulnerability against nature’s power. This approach established him as an initiator of the “sublime” landscape tradition.

Rosa’s scenes typically included bandits, soldiers, or wanderers navigating treacherous terrain. These elements added narrative tension to his works while highlighting the dangerous aspects of wilderness.

His dramatic use of light and shadow created moody atmospheres that would later influence Romantic painters. The turbulent energy in Rosa’s landscapes reflected his rebellious personality and desire to break from conventional artistic norms.

Satire and Philosophy

Rosa incorporated biting social commentary into his art through satirical elements and philosophical themes. His paintings often challenged societal norms and criticized corruption within political and religious institutions.

Works featuring philosophers like Diogenes and Democritus showcased Rosa’s interest in ancient philosophy. In “Democritus in Meditation,” he portrayed the philosopher contemplating human folly, reflecting Rosa’s own cynical worldview.

His “Allegory of Fortune” criticized the arbitrary nature of success and wealth. Rosa used rich symbolism in these works to convey complex ideas about justice, virtue, and human nature.

Rosa’s satires employed visual metaphors that were both sophisticated and accessible. He balanced philosophical depth with theatrical elements that engaged viewers on multiple levels.

Witchcraft and the Occult

Rosa’s fascination with the supernatural produced some of his most distinctive works. His scenes of witchcraft and sorcery depicted dark rituals, mysterious ceremonies, and magical incantations in shadowy forest settings.

The Finding of Moses (1660–65) by Salvator

These occult-themed paintings featured witches performing rituals among bones, strange artifacts, and twisted trees. Rosa created eerie atmospheres through carefully controlled lighting and bizarre anatomical details.

Unlike many artists who depicted witchcraft to condemn it, Rosa approached the subject with curiosity. His treatment suggested a personal interest in esoteric knowledge and the boundaries of accepted belief.

These works reflected broader cultural anxieties about the unknown. Rosa’s occult scenes established him as a pioneer in depicting the supernatural in art, influencing later Gothic and Romantic traditions.

Multifaceted Talents and Contributions

Salvator Rosa stood out among his contemporaries as a Renaissance man who excelled in multiple artistic disciplines. His creative energy extended far beyond painting into etching, poetry, music, writing, and theatrical performance.

Works in Etching and Printmaking

Rosa developed considerable skill as an etcher and printmaker, creating approximately 85 etchings during his lifetime. His printmaking style featured dramatic contrasts between light and dark, mirroring the intense emotional quality found in his paintings.

Saint John the Baptist Baptizing Christ in the Jordan (c. 1655)

Rosa’s etchings often depicted bandits, witches, and soldiers in wild landscapes. These works circulated widely throughout Europe, spreading his artistic vision and reputation.

Unlike many contemporaries who created prints after their paintings, Rosa approached etching as an independent art form. He developed unique techniques for creating texture and atmospheric effects using finely controlled acid baths and precise line work.

His most famous print series include “Figurine,” featuring soldiers and bandits, and “The Wishes,” which showcased his satirical perspective on human folly.

Poetry and Music

Rosa wrote satirical poetry that criticized the art world and society of his time. His most notable poetic work, “Satire,” targeted the corruption he observed in artistic circles and the broader culture.

As a musician, Rosa played the lute and composed songs that he would perform at gatherings. These musical talents enhanced his reputation in Roman intellectual circles and provided entry into exclusive academies.

His home in Rome became a meeting place for poets, musicians, and philosophers. These gatherings, known as “conversazioni,” allowed Rosa to showcase his multiple talents while building important connections.

Rosa’s writings on art theory influenced later generations of artists. His letters reveal strong opinions about artistic independence and the importance of individual expression over following established conventions.

Acting and Theater

Rosa’s theatrical talents emerged during carnival seasons in Rome, where he created comedic performances that delighted audiences. He played the character Formica, a witty commentator on social issues and artistic trends.

Mercury and the Dishonest Woodsman (ca. 1663) by Salvator Rosa

His theatrical productions often included improvisational elements and satire directed at competitors and critics. These performances demonstrated his quick wit and willingness to challenge authority.

Rosa designed sets and costumes for his theatrical works, bringing his visual sensibility to the stage. His experience in theater influenced his painting style, particularly in his dramatic use of gesture and expression.

Through acting, Rosa developed a public persona that enhanced his artistic reputation. This theatrical presence followed him throughout his career, making him one of the most memorable artistic personalities of the 17th century.

Frequently Asked Questions

Salvator Rosa’s distinctive artistic vision has sparked many questions about his style, subjects, and creative influences. His diverse body of work continues to fascinate art historians and enthusiasts alike.

What artistic styles and influences are evident in Salvator Rosa’s paintings?

Salvator Rosa’s work blends Baroque elements with a uniquely personal style that anticipated Romanticism. His paintings show influences from Neapolitan artists like Aniello Falcone, under whom he studied battle painting techniques.

Rosa developed a dramatic style characterized by dark colors, stormy skies, and wild landscapes. This approach stood in contrast to the more serene classical landscapes popular during his time.

His work also shows the influence of Caravaggio in his use of strong light and shadow effects. Rosa’s unconventional approach made him less popular with traditional patrons but would later inspire Romantic painters.

Can you describe the significance of Rosa’s self-portraits within his body of work?

Rosa’s self-portraits reveal his complex personality and artistic identity. He often portrayed himself as a philosopher or melancholic thinker, emphasizing his intellectual aspirations beyond being merely a painter.

These self-representations helped establish Rosa’s public image as a rebellious, independent artist. In several portraits, he depicted himself in dramatic poses with intense expressions, reinforcing his reputation for emotional depth.

His self-portraits served as promotional tools as well, circulating his image and personal brand to potential patrons and admirers. This strategic self-fashioning was relatively innovative for 17th-century artists.

How did philosophy inform the subject matter of Salvator Rosa’s artworks?

Rosa incorporated Stoic philosophy into many of his paintings, exploring themes of mortality, virtue, and human folly. His works often feature philosopher figures in contemplative poses within wild landscapes.

He created several paintings depicting ancient philosophers like Diogenes, using these historical figures to comment on contemporary society. Rosa’s philosophical paintings frequently contained moral messages critiquing corruption and superficiality.

Rosa’s interest in Neoplatonic ideas also appears in his allegorical works, where he explored concepts like the relationship between nature and human experience. This philosophical depth distinguished his work from many contemporaries.

What is the range of Rosa’s landscape works, and what themes do they typically explore?

Rosa’s landscapes range from intimate woodland scenes to vast, mountainous vistas dominated by stormy skies and jagged formations. He pioneered the “sublime” landscape that evokes feelings of awe and even terror.

His landscapes often include small human figures dwarfed by nature, suggesting humanity’s vulnerability. Bandits, soldiers, and wanderers frequently appear in these works, adding narrative elements to his natural settings.

Rosa painted both real and imagined locations, sometimes combining elements from different places to create more dramatic compositions. His marine paintings similarly feature turbulent seas and shipwrecks, emphasizing nature’s destructive power.

Are there any notable operas or compositions attributed to Salvator Rosa, and how do they relate to his visual art?

While Rosa himself was not a composer, his life and works inspired several operas and musical compositions. The most famous is “Salvator Rosa” (1874), an opera by Antonio Carlos Gomes that dramatizes Rosa’s life.

Rosa was actually a talented musician and poet in addition to his painting. He wrote satires and composed music for private performances, showing his diverse creative abilities.

These musical interpretations often emphasize the romantic and adventurous aspects of Rosa’s biography, including legends about him joining a band of outlaws. This musical legacy reflects how Rosa’s artistic persona transcended his paintings.

How does Salvator Rosa’s ‘A Rocky Coast’ fit into the broader context of his oeuvre?

“A Rocky Coast” exemplifies Rosa’s masterful approach to sublime landscape painting. It features dramatic rock formations and a turbulent atmosphere. The painting demonstrates his signature style of creating foreboding natural environments.

This work showcases Rosa’s technical skill in rendering geological features. He does this with both scientific observation and emotional impact. The small human figures in the composition follow his typical practice of emphasizing nature’s overwhelming scale.

“A Rocky Coast” connects to Rosa’s broader exploration of wild, untamed landscapes as metaphors for emotional and philosophical states. It represents his rejection of idealized classical landscapes in favor of more emotionally evocative natural settings.