Andrew Wyeth Painter: A Master of American Realism

Born: 12 July 1917, Pennsylvania, U.S.

Death: January 16, 2009, Pennsylvania, U.S.

Art Movement: Regionalism, Realism

Nationality: American

Influenced By: David Thoreau

Teachers: N.C. Wyeth (His Father)

Andrew Wyeth Painter: A Master of American Realism

Life and Career of Andrew Wyeth

Andrew Wyeth (1917-2009) established himself as one of America’s most significant realist painters of the 20th century. His detailed, often stark representations of rural landscapes and people captured an essence of American life that resonated deeply with audiences worldwide.

Early Life and Artistic Inclination

Born on July 12, 1917, in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, Andrew Wyeth grew up immersed in art. His father, N.C. Wyeth, was a famous illustrator who provided Andrew with his only formal artistic training.

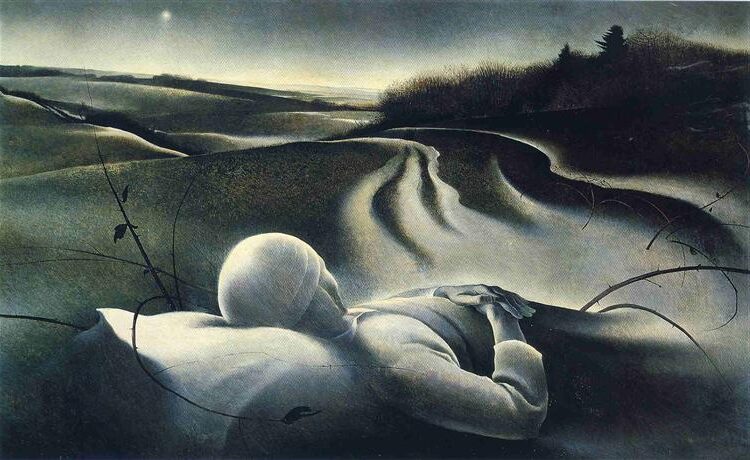

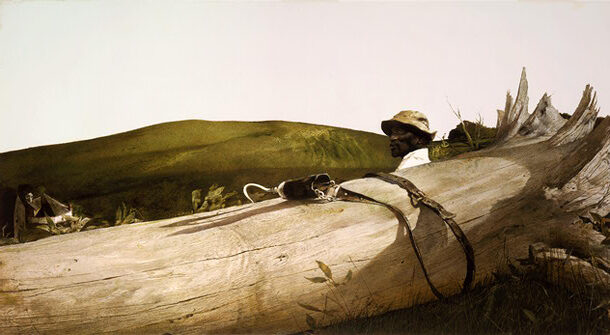

Rest in Peace by Andrew Wyeth

Young Andrew began drawing at an early age and showed exceptional talent. He had his first watercolor exhibition at age 20 at the Macbeth Gallery in New York City. This 1937 show sold out completely, launching his career.

The rural environments of Chadds Ford and his summer home in Cushing, Maine, deeply influenced his artistic vision. These two locations would provide the settings and subjects for nearly all his future work.

A defining moment came in 1945 when his father died in a tragic accident. This loss profoundly affected Andrew’s artistic direction, bringing a deeper emotional quality to his work.

Significant Artistic Periods and Styles

Wyeth developed a distinctive style known as “magic realism,” combining precise detail with emotional depth. He primarily worked in egg tempera and watercolor, mediums that allowed him to achieve his characteristic delicate textures and subtle tones.

His early period in the 1940s featured luminous watercolors of Maine landscapes. After his father’s death, his work took on a more somber, introspective quality.

The 1950s and 1960s marked Wyeth’s mature period. During this time, he created many of his most recognized works, including “Christina’s World” (1948), which became an American icon.

The “Helga Pictures,” revealed to the public in 1986, formed another significant period. This series included 247 studies of neighbor Helga Testorf created over 15 years, demonstrating his commitment to intensive, private artistic exploration.

Major Works and Achievements

“Christina’s World” (1948) remains Wyeth’s most recognized painting. This tempera work depicts his neighbor Christina Olson crawling across a field toward her home. The painting now hangs in the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

Christina’s World, 1948 by Andrew Wyeth

Other notable works include:

- “Winter 1946” (1946)

- “The Hunter” (1943)

- “Wind from the Sea” (1947)

- “Distant Thunder” (1961)

- “The Helga Pictures” series (1971-1985)

Wyeth received numerous accolades throughout his career. In 1963, President Kennedy awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He was the first living American artist to receive a retrospective at the White House.

In 1977, he became the first American artist since John Singer Sargent to be elected to the French Académie des Beaux-Arts. His work appears in major museums worldwide.

Personal Life and Inspirations

Wyeth married Betsy James in 1940, who became not only his wife but also his business manager and strongest advocate. They had two sons, Nicholas and Jamie, with Jamie following in his father’s footsteps as a renowned artist.

The people in Wyeth’s immediate surroundings deeply inspired his work. Christina and Alvaro Olson, Karl and Anna Kuerner, and Helga Testorf became frequent subjects. He developed intense connections with these individuals, seeing in them qualities that embodied the essence of the locations he painted.

Nature played a crucial role in his artistic vision. Wyeth found beauty in the stark winter landscapes of Pennsylvania and the rugged coastal scenes of Maine. He once stated, “I prefer winter and fall, when you feel the bone structure of the landscape.”

His work reflected a deep sense of place and time, often capturing moments of stillness and solitude that reveal universal human emotions.

Legacy and Influence

Andrew Wyeth died on January 16, 2009, at age 91, leaving behind an extraordinary artistic legacy. His work bridged traditional and modern art, maintaining representational techniques during an era dominated by abstract expressionism.

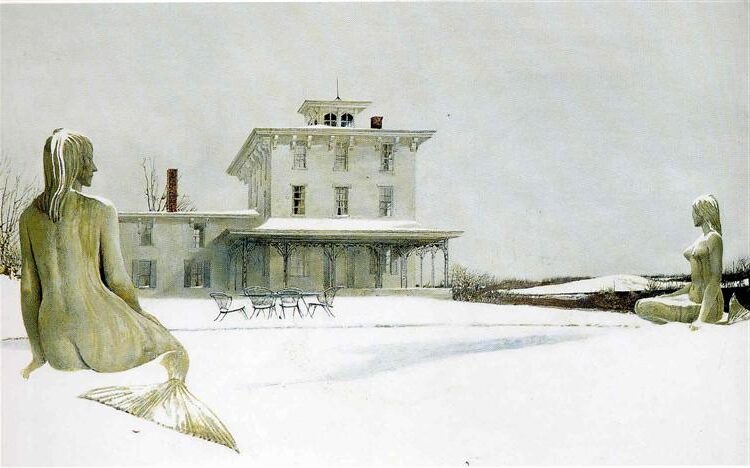

Painter’s Folly, 1989 by Andrew Wyeth

The Wyeth family artistic tradition continues through his son Jamie Wyeth, creating a three-generation artistic legacy that spans American art history.

Major museums including the Brandywine River Museum in Pennsylvania and the Farnsworth Art Museum in Maine preserve and celebrate his work. His paintings consistently achieve some of the highest prices for American art at auction.

Despite occasional criticism from modernist critics, Wyeth’s popularity with the public never wavered. His technical mastery and emotional resonance maintain his reputation as one of America’s most important painters of the 20th century.

Artistic Techniques and Themes

Andrew Wyeth developed distinctive artistic methods and recurring motifs that established his unique position in American art. His technical mastery combined with deeply personal symbolism created works that continue to resonate with viewers decades after their creation.

Realism and Precisionism

Wyeth’s approach to realism diverged from photographic representation, instead capturing what he called the “hidden aspects” of his subjects. His technique of drybrush—applying nearly dry paint with a brush—allowed him to achieve extraordinary detail and texture.

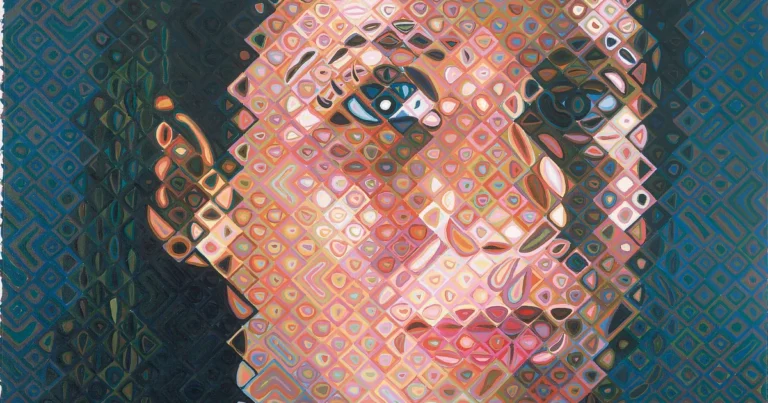

Field Hand (recto), 1985 by Andrew Wyeth

Wyeth practiced tempera painting, an egg-based medium that dries quickly and produces matte surfaces with remarkable permanence. This painstaking method required him to build images layer by layer, often taking months to complete a single work.

His precisionist tendencies emerged in works like “Christina’s World” (1948), where each blade of grass receives careful attention. Unlike pure precisionists, however, Wyeth infused his technical accuracy with emotional weight.

Wyeth once noted: “I prefer winter and fall, when you feel the bone structure of the landscape. Something waits beneath it; the whole story doesn’t show.”

Use of Color and Light

Wyeth employed a deliberately restricted palette dominated by earth tones—browns, grays, whites, and muted greens. This limited color range created a sense of austerity that matched his often stark subject matter.

His masterful handling of light became a signature element. Wyeth captured the distinctive quality of winter light in Pennsylvania and Maine, where harsh illumination could transform ordinary objects into something poetic.

In works like “Wind from the Sea” (1947), he demonstrated how subtle variations in white could convey the presence of light filtering through sheer curtains.

Wyeth’s watercolors often display more spontaneity than his tempera paintings, with luminous washes suggesting atmosphere and mood. These works show his remarkable ability to preserve white spaces in the paper to indicate light.

Portraiture and Landscapes

Wyeth’s portraits reveal his deep connection to his subjects, many of whom were neighbors in Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, or Cushing, Maine. His most famous subject, Helga Testorf, appeared in over 240 works created secretly over 15 years.

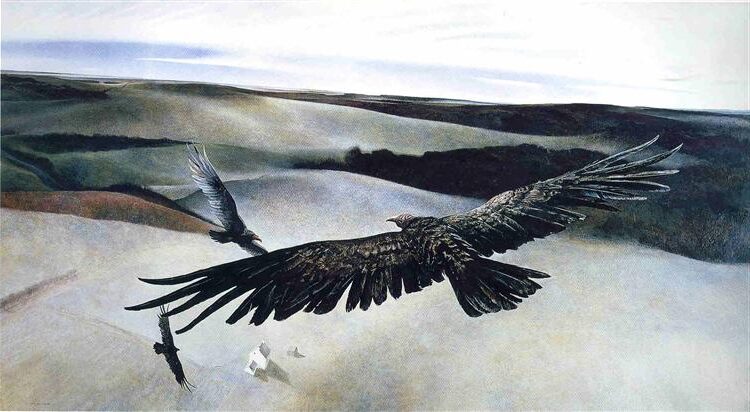

Soaring by Andrew Wyeth

His portrait approach often involved extended study of the subject, resulting in intimate psychological insights. Wyeth explained: “I do not paint for the public. I paint what interests me and means something to me.”

Landscapes in Wyeth’s work rarely exist as mere settings. Each field, hill, and farmhouse carried personal significance. The Olson house, featured in “Christina’s World,” became an iconic American image through his treatment.

Wyeth frequently painted interiors that suggest human presence even when empty. Windows, doorways, and worn furniture became proxies for their absent inhabitants.

Symbolism and Narrative

Objects in Wyeth’s paintings frequently carry symbolic weight. Weathered tools, animal bones, and abandoned structures represent mortality and the passage of time. A dory beached on shore might suggest isolation; a window, contemplation or longing.

His narrative approach often leaves stories intentionally unresolved. Wyeth provides visual clues but allows viewers to construct meaning, creating tension between what is shown and what remains hidden.

The “Helga Pictures” series demonstrates his use of narrative across multiple works, tracking subtle changes in subject and setting over time. This sequential approach created rich, evolving stories within his body of work.

Wyeth’s father’s death in a 1945 accident profoundly influenced his art, introducing themes of loss and memory that would persist throughout his career. Many paintings contain subtle references to his father’s influence.

Exhibitions and Collections

Andrew Wyeth’s work has been featured in numerous prestigious exhibitions and is housed in important collections around the world. His tempera paintings and watercolors continue to draw significant attention from both art institutions and the public.

Noteworthy Solo Exhibitions

The Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts hosted a major Andrew Wyeth exhibition in 1966, which subsequently traveled to the Baltimore Museum of Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, and Art Institute of Chicago. This traveling exhibition helped cement Wyeth’s reputation as one of America’s foremost realist painters.

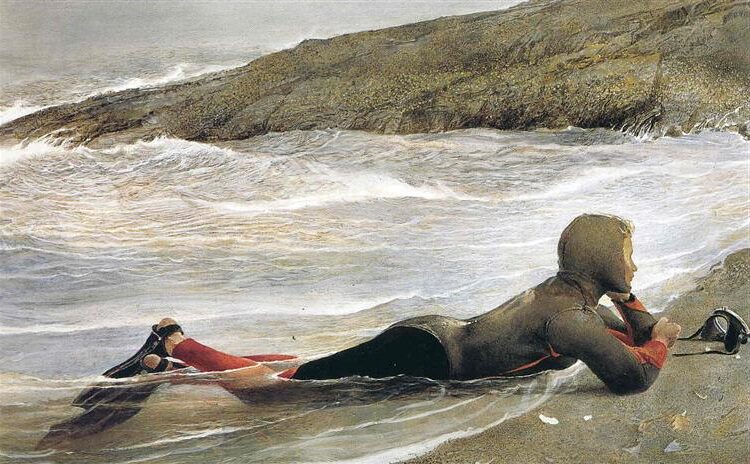

Scuba, 1994 by Andrew Wyeth

More recently, “Andrew Wyeth: Life and Death” became the first public presentation of newly rediscovered drawings where the artist imagined his own funeral. This introspective collection revealed a more personal side of Wyeth’s artistic vision.

The Brandywine River Museum regularly features Wyeth’s work, including a recent exhibition “Andrew Wyeth: Tempera Paintings” running from April 6 to September 8, 2024. These exhibitions highlight his mastery of the challenging tempera medium.

Permanent Collections and Galleries

The Andrew & Betsy Wyeth Study Center serves as a dedicated space for scholars and the public to engage with Wyeth’s art. Its mission focuses on encouraging diverse scholarly and creative interactions with his work.

The Greenville County Museum of Art (GCMA) maintains a significant collection of Wyeth’s pieces. Their permanent collection allows visitors to explore the evolution of his artistic development throughout his career.

The Smithsonian American Art Museum houses several important Wyeth works, making his art accessible to millions of visitors annually. His paintings “Christina’s World” and “Wind from the Sea” at the Museum of Modern Art are among the most recognized American paintings of the 20th century.

Critical Reception and Public Perception

Wyeth’s work has consistently provoked strong reactions from critics and the public alike. Some critics dismissed his work as sentimental or illustrative, while others praised his technical virtuosity and emotional depth.

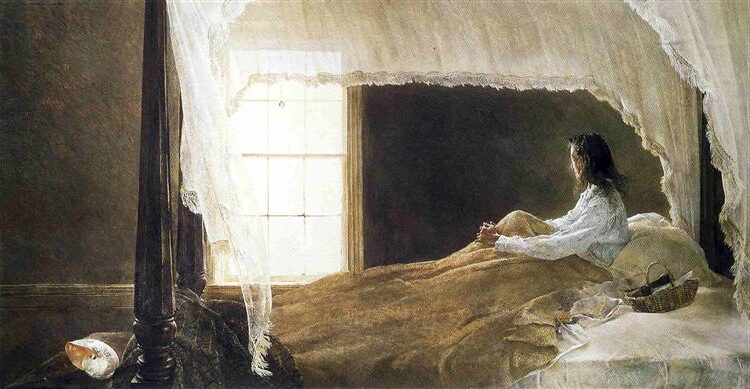

Chambered Nautilus by Andrew Wyeth

The “Helga Pictures,” a series of 247 studies of his neighbor Helga Testorf created in secret over 15 years, caused a sensation when revealed in 1986. The series sparked debates about artistic obsession and privacy.

Despite mixed critical reception, Wyeth’s paintings remain enormously popular with the public. His precisely rendered landscapes and figures speak to American identity and rural life in ways that continue to resonate with viewers today.

Frequently Asked Questions

Andrew Wyeth’s distinctive artistic approach and significant contributions to American art have prompted many questions. His realistic style, personal connections, and artistic influences shaped his celebrated works and lasting impact.

What are the defining characteristics of Andrew Wyeth’s artistic style?

Andrew Wyeth was primarily known as a realist painter who captured his subjects with remarkable precision and detail. His work featured a muted color palette dominated by earth tones, creating a somber, contemplative mood.

Wyeth mastered the egg tempera technique, which allowed him to create highly detailed textures and surfaces. His paintings often portrayed rural landscapes and interiors from Pennsylvania and Maine.

A sense of isolation, nostalgia, and emotional depth permeates his work. Wyeth’s attention to light and shadow created powerful compositions that evoke strong emotional responses.

Can you list some of the most significant works by Andrew Wyeth, and why they are important?

“Christina’s World” (1948) is perhaps Wyeth’s most iconic painting, depicting a woman crawling across a field toward a distant farmhouse. This work captures themes of isolation, perseverance, and connection to place that defined much of his art.

“Winter 1946” reflects his grief following his father’s tragic death. The haunting image of a boy running downhill represents Wyeth’s emotional state during this difficult period.

“Helga Pictures,” a series of 247 paintings created over 15 years, gained notoriety when revealed in 1986. These intimate portraits demonstrate Wyeth’s technical mastery and deep connection to his subjects.

How did Andrew Wyeth’s upbringing and personal life influence his artwork?

Andrew Wyeth was born in 1917 to N.C. Wyeth, a famous illustrator who became his only formal teacher. This relationship significantly shaped his artistic development and work ethic.

Wyeth’s deep connections to Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania and Cushing, Maine—where his family maintained homes—provided the settings and subjects for most of his paintings throughout his life.

Personal relationships often inspired his most powerful works. His neighbors, friends, and landscapes he knew intimately became recurring subjects that gained depth and meaning through his unique perspective.

What role did the Brandywine School play in shaping Andrew Wyeth’s career as a painter?

The Brandywine School, founded by Howard Pyle, influenced Wyeth through his father N.C. Wyeth, who studied with Pyle. This tradition emphasized narrative quality and meticulous technique.

Though Andrew did not formally study at the school, he absorbed its emphasis on observation, draftsmanship, and storytelling through his father’s teachings and example.

The Brandywine tradition’s focus on American subjects and landscapes aligned with Wyeth’s interest in portraying rural American life. This foundation helped him develop his distinctive artistic voice while maintaining connections to this regional artistic heritage.

In what ways did Andrew Wyeth contribute to or differ from the American realism movement?

Wyeth contributed to American realism through his extraordinary technical precision and emotional depth. In 1990, he became the first artist awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, recognizing his significant cultural contributions.

Some realists focused purely on visual accuracy. In contrast, Wyeth infused psychological and emotional dimensions into his work. He referred to his approach as “painting from the inside out.”

Abstract expressionism dominated mid-20th century American art. However, Wyeth maintained his figurative style. This commitment to representation when it was considered unfashionable eventually earned him recognition for his authentic artistic vision.

How has Andrew Wyeth’s legacy persisted or evolved in the contemporary art world?

Museums continue to celebrate Wyeth’s work through major exhibitions. This ensures his paintings remain accessible to new generations. The Andrew Wyeth Museum in Chadds Ford preserves his studio and artwork.

Contemporary realist painters frequently cite Wyeth as an inspiration. They admire both his technical mastery and emotional resonance. His influence extends beyond technique to his ability to find profound meaning in ordinary subjects.

The art world has become more accepting of representational art. As a result, Wyeth’s work has experienced renewed appreciation. Critics now recognize how his seemingly simple scenes contain complex psychological dimensions and technical brilliance.