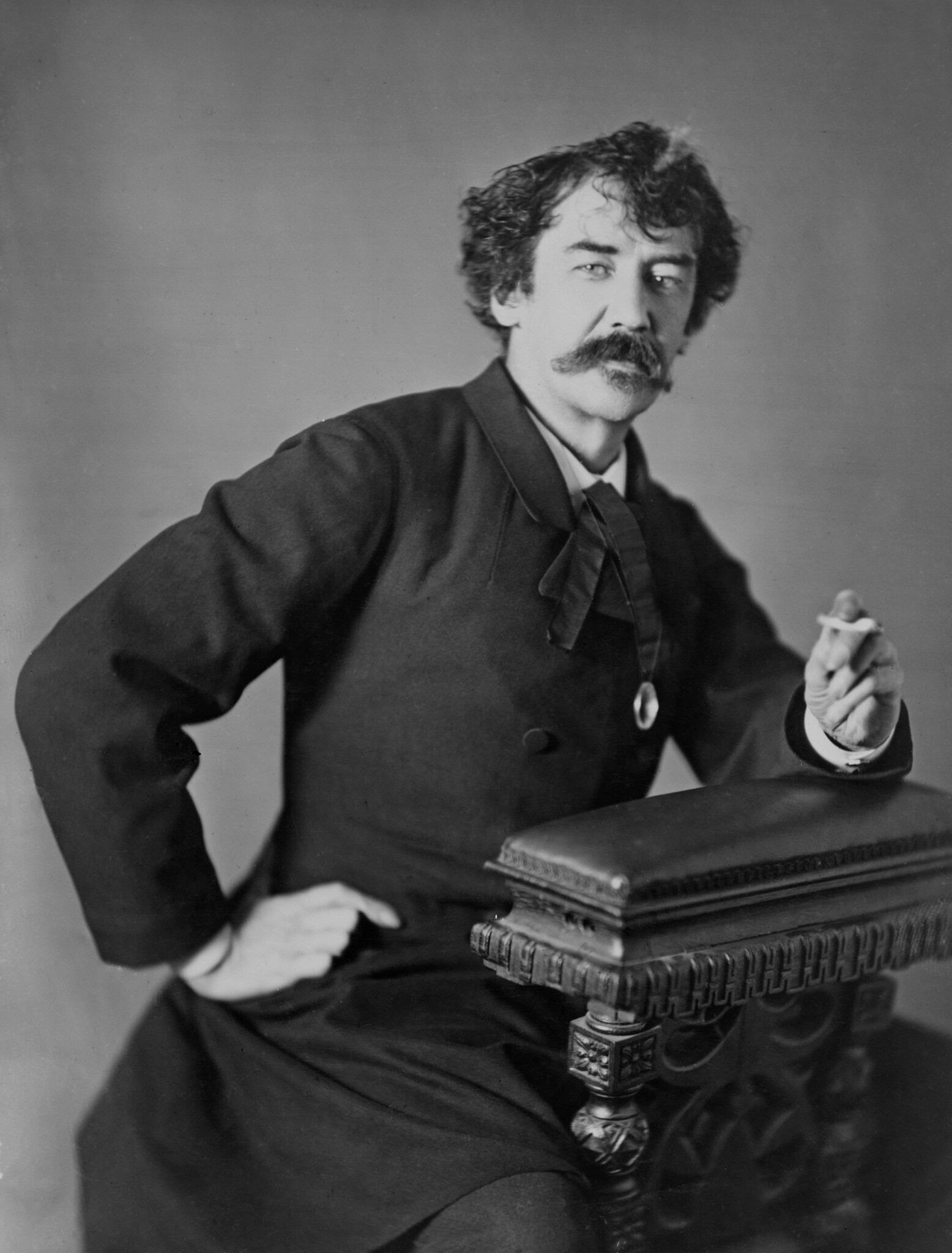

James McNeill Whistler Painter: The Visionary Behind Nocturne and Arrangement in Grey and Black

Born: July 10, 1834, Lowell, Massachusetts, US

Death: July 17, 1903, London, England, UK

Art Movement: Tonalism

Nationality: American

Institution: Imperial Academy of Arts

James McNeill Whistler Painter: The Visionary Behind Nocturne and Arrangement in Grey and Black

Life and Early Career of James McNeill Whistler

James McNeill Whistler emerged as one of the most distinctive American artists of the 19th century, though he spent much of his life abroad. His journey from Massachusetts to becoming a leading figure in the art world spans continents and reflects his unique artistic vision.

Biographical Beginnings in Lowell, Massachusetts

James Abbott McNeill Whistler was born on July 11, 1834, in Lowell, Massachusetts. His father, Major George Washington Whistler, worked as a civil engineer, which led the family to move to St. Petersburg, Russia when James was just nine years old.

Zaandam, the Netherlands, c. 1889, by James McNeill Whistler

The young Whistler showed artistic talent early in life. After his father’s death in 1849, the family returned to the United States. Whistler’s mother, a devout Christian, hoped her son would become a minister, but his artistic inclinations prevailed.

In 1851, he entered the United States Military Academy at West Point. His time there proved unsuccessful, and he was eventually dismissed in 1854 for poor chemistry grades and a rebellious attitude.

European Influence and Art Education

After leaving West Point, Whistler moved to Paris in 1855 to pursue art seriously. He studied briefly at the École Impériale et Spéciale de Dessin and later at Charles Gleyre’s studio, where he embraced bohemian life.

In Paris, Whistler became influenced by Realism and the work of Gustave Courbet. He also developed a fascination with Japanese art, which would later influence his aesthetic principles.

During this formative period, Whistler befriended other artists including Henri Fantin-Latour and Alphonse Legros. The American Civil War erupted during this time, but Whistler, now fully committed to his artistic path, remained in Europe rather than returning home.

The Birth of an American Artist in London

Whistler relocated to London in 1859, where he would spend most of his remaining life. This move marked the beginning of his most productive artistic period.

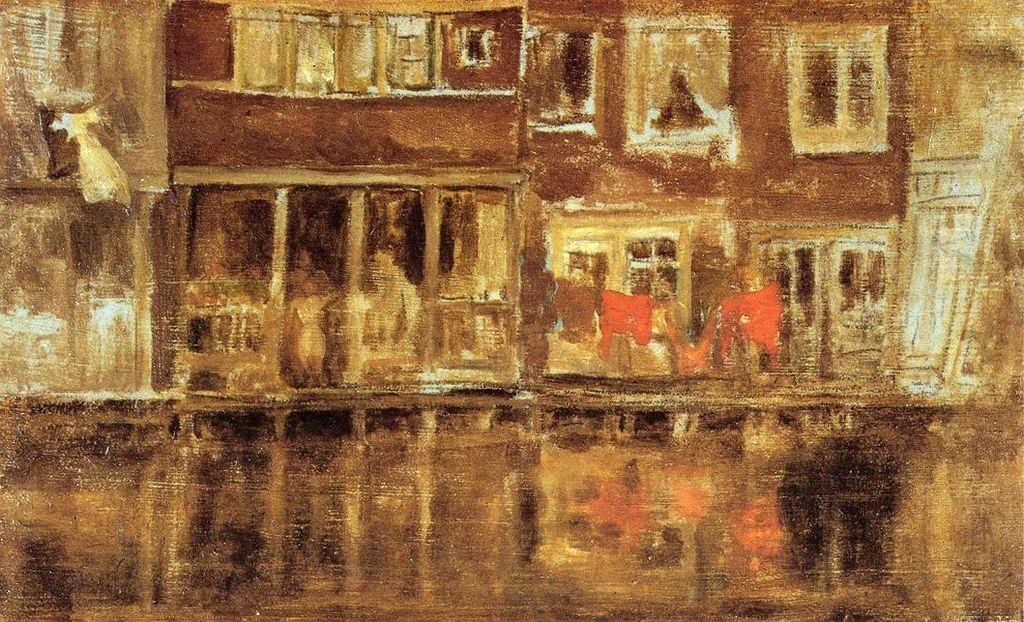

The Canal, Amsterdam, 1889, by James McNeill Whistler

In London, he developed his distinctive style, moving away from the narrative traditions of Victorian painting. His nocturnal scenes of the Thames, which he called “nocturnes,” became some of his most celebrated works.

During the American Gilded Age, Whistler emerged as a leading proponent of “art for art’s sake.” He rejected sentimentality in painting and focused on visual harmony and aesthetics rather than moral messages.

By the 1870s, Whistler had established himself as a controversial but important figure in the London art world. His personality was as bold as his art – he engaged in public feuds, including a famous lawsuit against critic John Ruskin, and cultivated a flamboyant persona with his pointed wit.

Artistic Contributions and Techniques

James McNeill Whistler revolutionized the art world with his innovative approaches to painting and printmaking. His emphasis on tonal harmony and “art for art’s sake” principles challenged Victorian conventions and influenced generations of artists who followed.

Innovations in Painting and Printmaking

Whistler developed unique techniques that set him apart from his contemporaries. He often thinned his oils to create translucent layers, allowing him to achieve subtle tonal variations in his works.

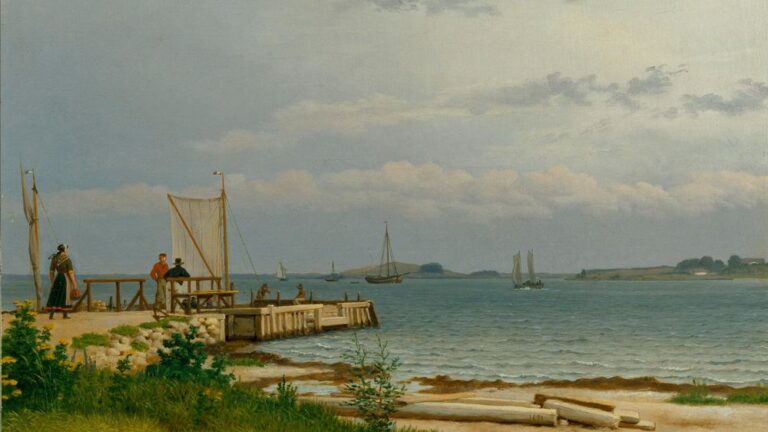

The Bathing Posts, Brittany, 1893, by James McNeill Whistler

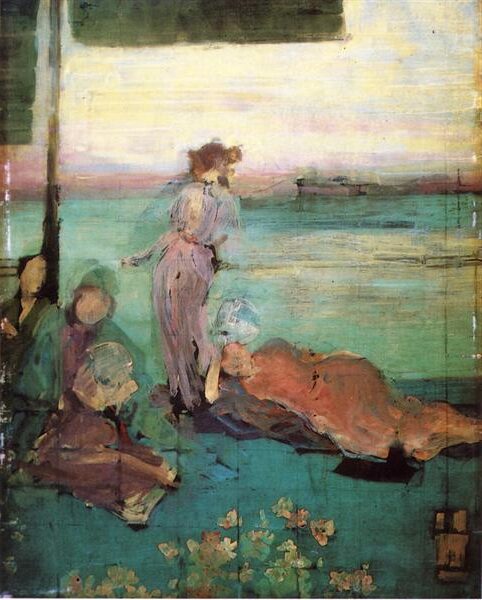

His approach to color was revolutionary – he used restricted palettes and named paintings as “arrangements,” “harmonies,” or “nocturnes” rather than by subject matter. This naming convention emphasized his belief that visual elements were more important than narrative content.

In printmaking, Whistler excelled at etchings and lithographs. He created over 400 etchings throughout his career, demonstrating exceptional technical skill and sensitivity to line and composition.

His work in pastels and watercolors showed similar innovation, with Japanese influences evident in his simplified forms and asymmetrical compositions.

Significant Works: ‘Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1’ and Beyond

“Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1” (popularly known as “Whistler’s Mother”) remains his most famous painting. Completed in 1871, it showcases his mastery of tonal harmony and compositional balance.

Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1, 1871, by James McNeill Whistler

The seated portrait of his mother appears austere but reveals subtle gradations of black, gray, and cream tones. The painting became an iconic image of motherhood despite Whistler’s intentions for it to be appreciated purely for its formal qualities.

“The Peacock Room,” commissioned by shipping magnate Frederick Leyland, represents Whistler’s most ambitious decorative project. The room featured gold peacocks on turquoise-blue walls, demonstrating his interest in total artistic environments.

His “Chelsea” period produced notable portraits that balanced realistic representation with aesthetic concerns about pattern and color relationships.

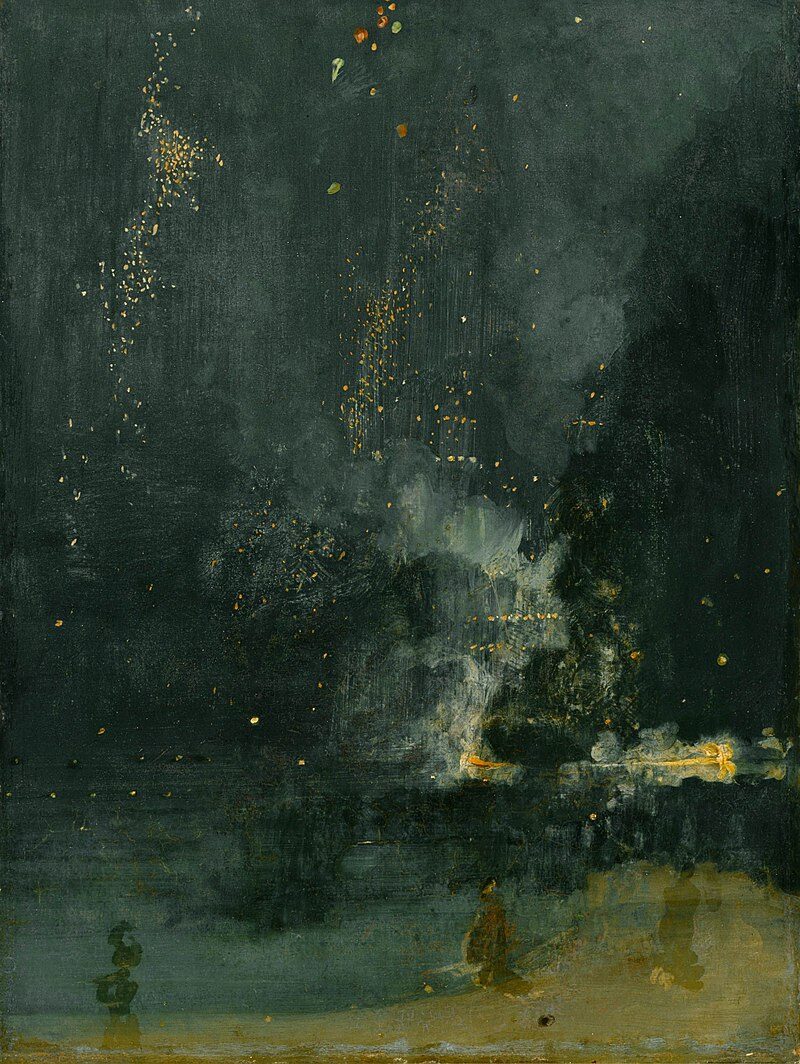

Nocturnes and the Aesthetic Philosophy

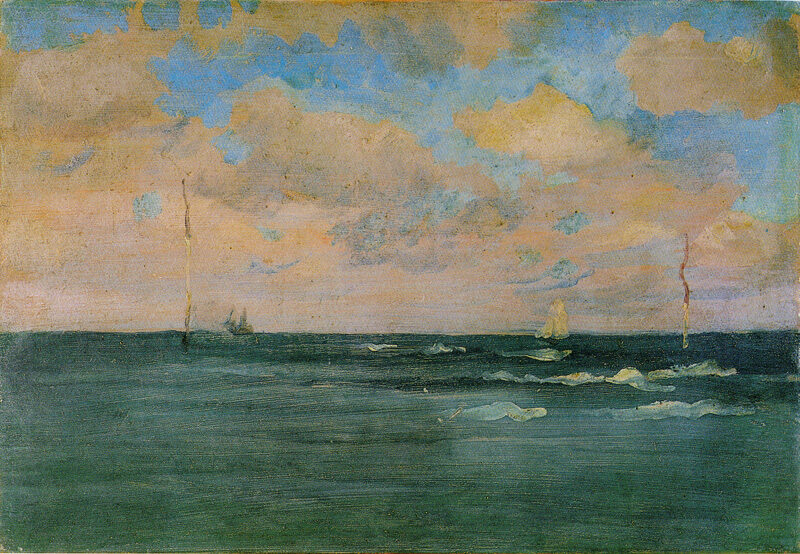

Whistler’s Nocturnes—atmospheric scenes of London’s Thames River at twilight—embodied his aesthetic philosophy. These misty, nearly abstract paintings captured fleeting light effects with minimal detail.

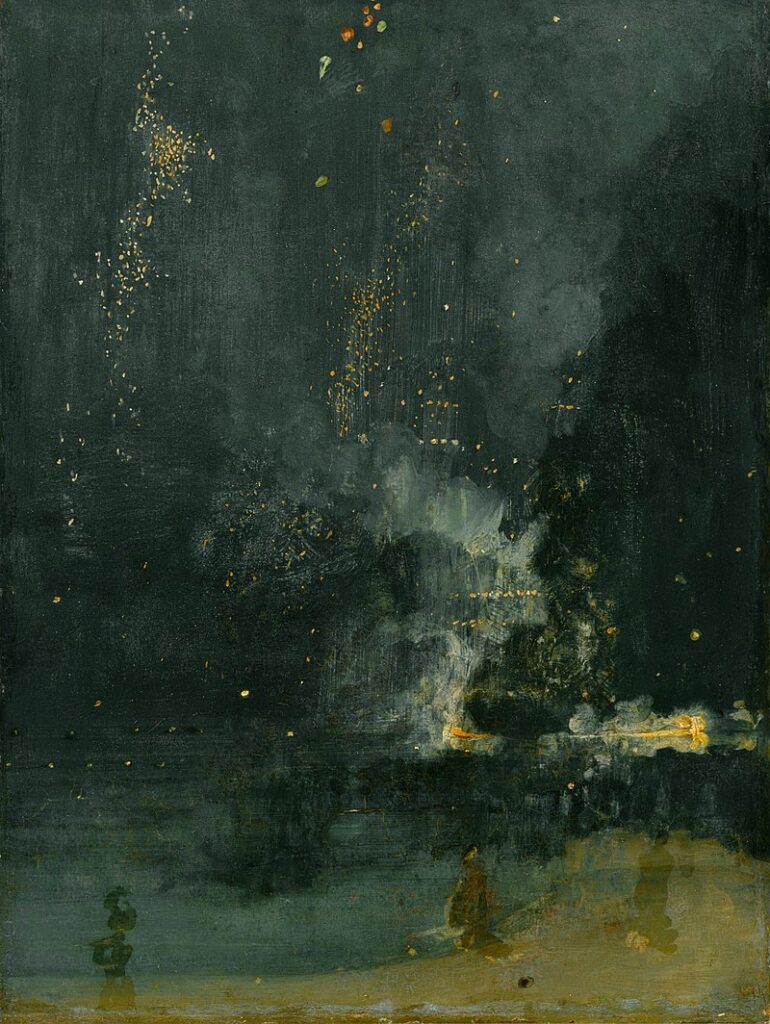

“Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket” triggered a famous legal battle with critic John Ruskin. The painting’s abstracted fireworks display over Cremorne Gardens exemplified Whistler’s belief that painting should aspire to the condition of music.

He defended these works as visual “harmonies” rather than literal depictions, supporting the Aestheticism movement’s “art for art’s sake” principles. His artistic signature—a stylized butterfly—reinforced this philosophy.

During the Gilded Age, Whistler’s emphasis on beauty over moral or narrative content challenged Victorian artistic conventions. His techniques influenced many artists working in England and beyond, establishing him as a pivotal figure bridging traditional and modern approaches to art.

Influence and Legacy

James McNeill Whistler left an indelible mark on the art world through his innovative techniques and philosophies. His rejection of sentimentality and embrace of “art for art’s sake” principles transformed how artists approached their work during the late 19th century and beyond.

Impact on Modern Art and Aesthetic Movement

Whistler emerged as a leading figure in the Aesthetic Movement, advocating for art that prioritized beauty and formal harmony over narrative or moral messages. His famous “Ten O’Clock Lecture” outlined his artistic philosophy, arguing that art should stand independent of storytelling or didactic purposes.

An Orange Note: Sweet Shop, 1884, by James McNeill Whistler

His musical titles like “Symphony in White” and “Nocturne: Blue and Gold” reflected his revolutionary concept that painting could aspire to the condition of music. This approach influenced many modern artists who explored abstraction and formal relationships.

Whistler’s subtle color harmonies and compositional techniques impacted Impressionists despite his resistance to being classified with them. His Anglo-Japanese style, incorporating elements from Japanese prints such as flattened space and high horizon lines, helped introduce Eastern aesthetic principles to Western art.

Artists like Édouard Manet appreciated Whistler’s bold simplifications and tonal arrangements. His influence extended to the next generation of painters who embraced his ideas about artistic independence and formal innovation.

Notable Exhibitions and Collections

Whistler’s work appears in prestigious museums worldwide. The Detroit Institute of Arts holds significant pieces, including “Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket,” the painting that triggered his famous libel suit against critic John Ruskin.

His 1880 trip to Venice produced a remarkable series of etchings and pastels that revitalized his career. These works, celebrated for their atmospheric qualities and technical mastery, remain highly valued in collections globally.

As founder and president of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers, Whistler organized influential exhibitions that promoted aesthetic principles. These shows helped establish new standards for exhibition design and artistic presentation.

His diverse output included over 500 paintings alongside numerous etchings, drypoints, lithographs, watercolors, and drawings. This versatility demonstrates his technical range and commitment to exploring various media.

Personal Life and Public Persona

Whistler cultivated a flamboyant public image that complemented his artistic identity. His distinctive appearance—featuring a monocle and white lock of hair—made him instantly recognizable in artistic circles.

Flower Market, 1885, by James McNeill Whistler

The infamous Ruskin trial of 1878 cemented Whistler’s reputation as an articulate defender of artistic freedom. Though he won the case, the minimal damages awarded led to bankruptcy, forcing him to sell his home and studio.

His most famous work, officially titled “Arrangement in Grey and Black No. 1” but known popularly as “Portrait of the Artist’s Mother,” reveals the complex relationship between his public and private personas. The painting’s restrained emotion and formal harmony reflect his artistic principles while depicting a deeply personal subject.

Whistler maintained important relationships with writers and fellow artists throughout his career. His correspondences reveal a quick wit and combative intellect that helped spread his artistic theories beyond the canvas.

Frequently Asked Questions

James McNeill Whistler sparked debate and innovation throughout his artistic career. His unique aesthetic approach and controversial personality left a lasting mark on the art world.

What is James McNeill Whistler best known for in the art world?

Whistler is most famous for his painting “Arrangement in Grey and Black No.1,” commonly known as “Whistler’s Mother.” This iconic work, completed in 1871, exemplifies his interest in tonal harmony and Japanese-influenced composition.

He also gained recognition for his nocturnal scenes of the Thames River, which he called “nocturnes.” These atmospheric paintings emphasized mood over detailed representation.

Whistler’s distinctive butterfly signature, which evolved throughout his career, became his personal artistic brand and appeared on paintings, correspondence, and publications.

How did the Aesthetic Movement influence Whistler’s work?

The Aesthetic Movement’s principle of “art for art’s sake” profoundly shaped Whistler’s approach. He rejected Victorian narrative traditions, instead focusing on visual harmony and beauty without moral messages.

Whistler’s musical titles like “Symphony,” “Arrangement,” and “Nocturne” reflected the movement’s interest in the relationship between different art forms. These titles emphasized the formal qualities of his works rather than their subjects.

His refined color schemes and simplified compositions demonstrated the Aesthetic Movement’s fascination with Japanese art and design principles.

Can you describe the significance of Whistler’s ‘Peacock Room’ and its historical context?

The Peacock Room, created between 1876-1877, represents one of Whistler’s most ambitious decorative projects. Originally commissioned by shipping magnate Frederick Leyland to display his porcelain collection, Whistler dramatically transformed the dining room beyond the agreed scope.

The room features elaborate peacock motifs in blue and gold, demonstrating Whistler’s interest in Asian aesthetics and total artistic environments. The project caused a significant rift with Leyland over artistic control and payment.

Now housed in the Freer Gallery in Washington D.C., the Peacock Room stands as a masterpiece of interior design and exemplifies the Anglo-Japanese style popular during that period.

What was the outcome and impact of the famous Ruskin-Whistler libel case on the artist’s career?

In 1877, critic John Ruskin harshly criticized Whistler’s “Nocturne in Black and Gold: The Falling Rocket,” claiming Whistler was “flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.” Whistler sued for libel and technically won the case but was awarded only a farthing in damages.

The trial financially ruined Whistler, forcing him into bankruptcy. He had to sell his house and many possessions to cover legal fees.

The case sparked important public debates about the nature of art and criticism. Whistler later published “The Gentle Art of Making Enemies,” which included transcripts from the trial and established his reputation as a sharp-witted defender of artistic freedom.

How did Whistler’s early life and education shape his approach to painting?

Born in America in 1834, Whistler spent part of his childhood in Russia where his father worked as a railway engineer. This early exposure to different cultures broadened his artistic perspective.

His brief education at West Point military academy taught him discipline and precision, qualities later reflected in his meticulous approach to composition and technique.

After moving to Paris in 1855, Whistler absorbed influences from Realism, Impressionism, and Japanese art, developing his distinctive style that blended these various elements.

In what ways did James McNeill Whistler contribute to the concept of ‘art for art’s sake’?

Whistler championed the idea that art should exist for beauty rather than moral instruction. His musical titles deliberately moved away from narrative content, focusing viewers’ attention on formal qualities like color and arrangement.

His famous “Ten O’Clock Lecture” in 1885 articulated his belief that art should be judged on its own merits rather than subject matter. He declared: “Art should be independent of all claptrap – should stand alone […] and appeal to the artistic sense of eye or ear.”

Whistler’s emphasis on subtle tonal variations and atmospheric effects pushed painting toward abstraction. This influenced future generations of artists to explore non-representational approaches.