Egon Schiele Painter: The Revolutionary Expressionist Who Transformed Modern Art

Born: 12 June 1890, Tulln an der Donau, Austria-Hungary

Death: 31 October 1918, Vienna, Austria-Hungary

Art Movement: Expressionism

Nationality: Austrian

Teacher: Christian Griepenkerl

Institution: Kunstgewerbeschule (School of Arts and Crafts) and Academy of Fine Arts Vienna

Egon Schiele Painter: The Revolutionary Expressionist Who Transformed Modern Art

Egon Schiele: A Brief Biography

Egon Schiele emerged as one of the most distinctive artists of Austrian Expressionism during his short but prolific career. His bold artistic vision and psychological depth left an indelible mark on 20th century art despite his tragically brief life.

Early Life and Education

Egon Schiele was born on June 12, 1890, in Tulln, Austria. His early childhood was marked by tragedy when his father died of syphilis when Egon was just 14 years old. This loss significantly impacted his psychological development and later artistic themes.

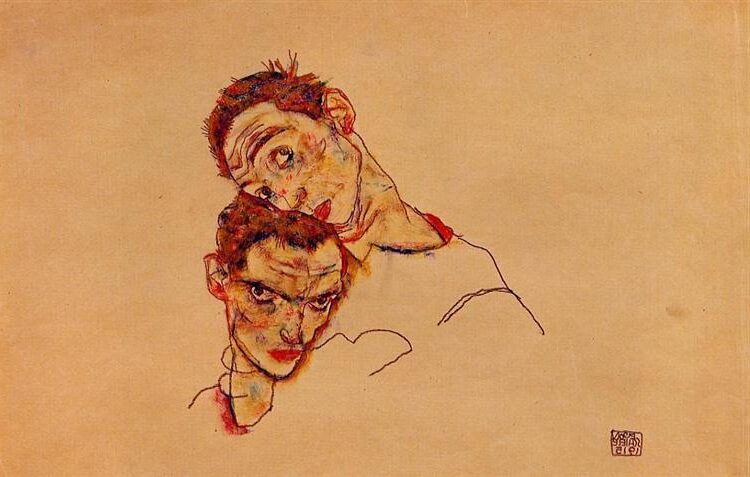

Double Self-Portrait (1915) by Egon Schiele

After attending schools in Krems and Klosterneuburg, Schiele showed remarkable artistic talent from a young age.

In 1906, he enrolled in the prestigious Akademie der Bildenden Künste (Academy of Fine Arts) in Vienna.

At the academy, Schiele quickly became frustrated with the conservative teaching methods. He found inspiration instead in the work of Gustav Klimt, who became his mentor and introduced him to the Vienna Secession movement, which was breaking away from traditional artistic conventions.

Career and Artistic Development

Schiele developed his distinctive style by 1910, characterized by angular, contorted figures, raw emotional expression, and unflinching psychological intensity. His early works often shocked viewers with their explicit sexuality and emotional frankness.

In 1909, Schiele co-founded the Neukunstgruppe (New Art Group) after leaving the Academy. This marked his definitive break with academic traditions and established him as a key figure in the Austrian Expressionist movement.

His artistic output was remarkably prolific. Despite his short career, Schiele created over 3,000 drawings and approximately 300 paintings, exploring themes of sexuality, death, and psychological turmoil.

Throughout his career, Schiele yearned to create grand allegorical murals like his mentor Klimt, but never found public commissions for such ambitious works.

Personal Life and Influences

Schiele’s personal life was often tumultuous and controversial. In 1912, he was briefly imprisoned on charges of seducing a minor, though these charges were eventually dropped. His explicit artwork was considered pornographic by many contemporaries.

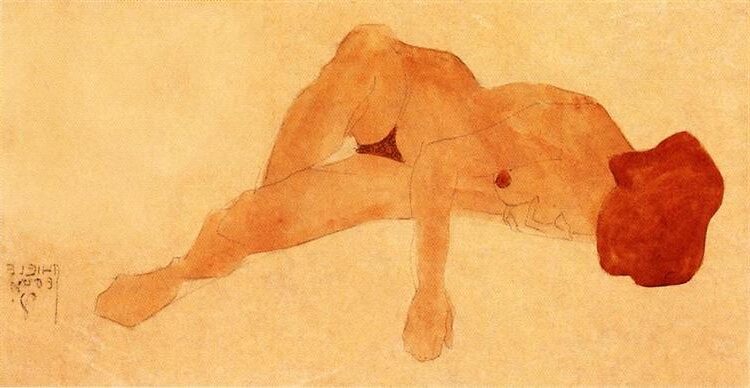

Nude (1917) by Egon Schiele

In 1915, Schiele married Edith Harms, but their marriage was cut short by tragedy. The Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 claimed both Edith, who was pregnant at the time, and Schiele himself, who died on October 31, 1918, at just 28 years old.

Klimt’s influence remained significant throughout Schiele’s career, though he developed his own distinctive artistic voice. The psychological theories of Sigmund Freud, particularly regarding sexuality, also impacted Schiele’s exploration of human psychology in his art.

Artistic Style and Techniques

Egon Schiele developed a distinctive artistic approach that set him apart from other artists of his time. His work featured bold experimentation with line, form, and color that challenged conventional aesthetics of the early 20th century.

Expressionist Aesthetics

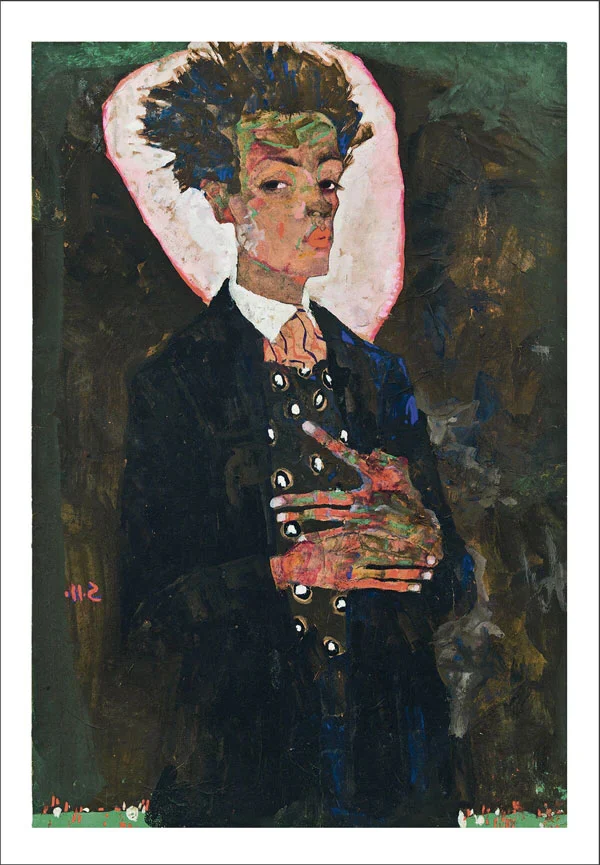

Schiele is primarily identified as an Expressionist painter who moved beyond realistic representation to convey emotional and psychological states. After initially studying at the Vienna Academy of Fine Art at sixteen, he quickly broke from academic traditions.

Two Women by Egon Schiele

His style emerged fully by age twenty, characterized by intensity and raw emotional content. Unlike other Expressionists who used bold colors to convey emotion, Schiele relied more on line distortion and composition.

The artist focused on exposing the inner turbulence of his subjects, particularly in his unflinching self-portraits and nude studies. His work explored themes of sexuality, mortality, and psychological tension in ways that were considered shocking and controversial during his lifetime.

Line and Form

Schiele’s masterful line work stands as his most recognizable artistic element. He favored contour drawing with strong, angular lines that created a sense of tension and energy.

His figures often feature elongated limbs, twisted postures, and exaggerated proportions that communicate psychological states rather than anatomical accuracy. The artist employed deliberate distortion to convey vulnerability, anxiety, or desire.

Schiele typically began with quick, spontaneous sketches, preserving a sense of immediacy even in his finished works. His hands were particularly expressive elements in his compositions, often portrayed with twisted fingers and emphasized joints.

The artist’s confident linework created figures that seem to vibrate with nervous energy against empty backgrounds, highlighting the isolation of his subjects.

Use of Color and Composition

Schiele’s color palette evolved throughout his career but usually featured earthy tones punctuated by unexpected bright accents. Early works show muted colors, while later paintings incorporate more vibrant hues.

Reclining Female Nude (1908) by Egon Schiele

He often left large portions of canvas unpainted, creating stark contrasts between subject and background. This negative space emphasized the isolation of his figures and created psychological tension.

The artist used color symbolically rather than realistically. Sickly greens and yellows in flesh tones suggested decay, while bright reds highlighted erotic elements or emotional intensity.

His compositions frequently placed figures in awkward, asymmetrical positions. Subjects might be cropped oddly or positioned at the edges of the frame, creating a sense of unease or claustrophobia that reinforced the emotional content of his work.

Notable Works and Exhibitions

“Self-Portrait with Peacock Waistcoat” (1911) exemplifies Schiele’s technical approach, featuring his characteristic angular lines and psychological intensity. “Death and the Maiden” (1915) demonstrates his mature style with its symbolic use of color and emotional depth.

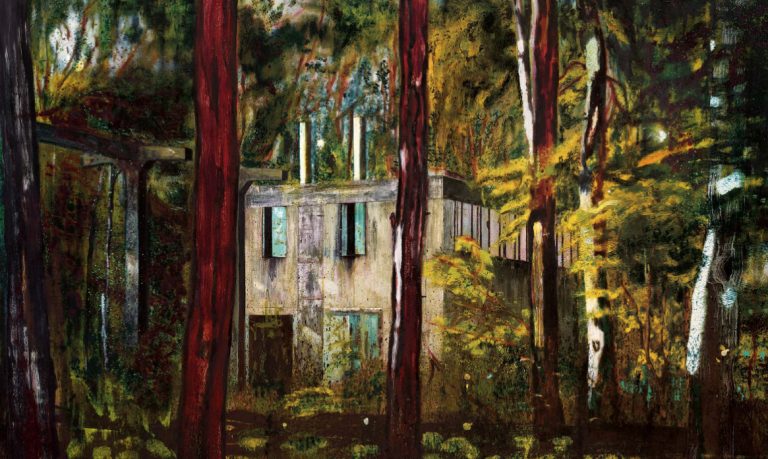

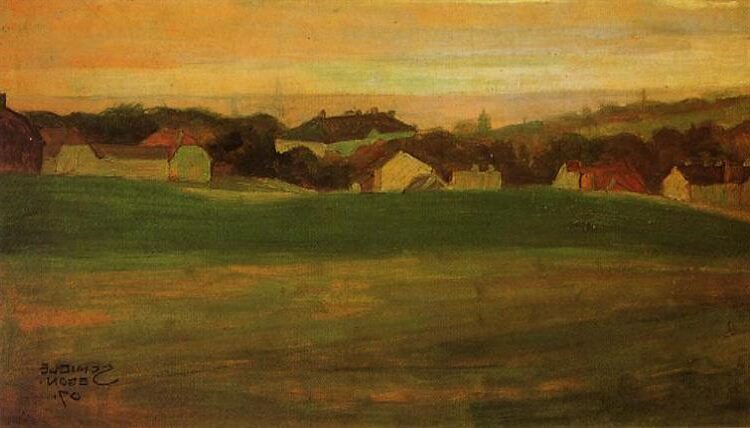

His 1918 series of cityscapes and landscapes shows a different aspect of his technique, with more structured compositions but still maintaining his distinctive line quality. These works were created shortly before his death from influenza at age 28.

Major exhibitions of his work during his lifetime included his first solo exhibition at Galerie Miethke in 1911. The 1912 exhibition at the Neukunstgruppe (New Art Group) further established his reputation despite public controversy over his explicit imagery.

Today, comprehensive collections of Schiele’s work can be found at the Leopold Museum in Vienna and the Neue Galerie in New York, showcasing the full range of his technical innovations.

Legacy and Impact on Modern Art

Egon Schiele’s brief but prolific career left an indelible mark on the art world that continues to resonate today. His raw emotional honesty and distinctive aesthetic have influenced generations of artists and secured his place in art history.

Contributions to Expressionism

Schiele expanded the boundaries of Expressionism by introducing unprecedented psychological intensity to his works. His distorted figures, angular lines, and bold use of negative space challenged traditional artistic conventions of the early 20th century.

Kneeling Girl, Resting on Both Elbows (1917) by Egon Schiele

His technique of using the human body as a vessel for emotional expression revolutionized portraiture. While artists before him depicted physical appearance, Schiele captured inner turmoil and vulnerability.

Many art historians credit Schiele with developing a unique sub-category within Expressionism that emphasized individual subjective experience. His unflinching portrayal of sexuality and mortality brought taboo subjects into artistic discourse.

Schiele’s color palette—often muted with strategic bright accents—became a hallmark of his style and influenced expressionist color theory.

Influence on Contemporary Artists

Lucian Freud cited Schiele as a major inspiration, particularly in his approach to nude portraiture. Freud’s psychological intensity and unflinching gaze echo Schiele’s earlier innovations.

Jean-Michel Basquiat’s raw, emotional line work shows clear parallels with Schiele’s drawing technique. Both artists used distortion to convey psychological states.

Contemporary artists like Jenny Saville have built upon Schiele’s legacy. Her large-scale paintings of bodies continue his tradition of using flesh as an emotional canvas.

Schiele’s influence extends beyond painting into fashion photography, graphic novels, and digital art. His distinctive poses and compositions regularly appear in editorial fashion spreads and advertising campaigns.

Preservation and Representation in Museums

The Leopold Museum in Vienna houses the world’s largest collection of Schiele works, with over 220 pieces. This comprehensive collection allows visitors to trace his artistic development.

Meadow with Village in Background (1907) by Egon Schiele

Major institutions like MoMA, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and the Albertina regularly feature Schiele in their exhibitions. His works consistently draw large audiences despite their controversial nature.

The Egon Schiele Art Centrum in Český Krumlov, Czech Republic, preserves his legacy in the town where he once lived and worked. This museum contextualizes his art within the cultural environment that shaped it.

Digital preservation efforts have made Schiele’s work more accessible worldwide. Online collections and high-resolution scans allow scholars and art lovers to study his technique in unprecedented detail.

Frequently Asked Questions

Egon Schiele’s controversial art and brief life continue to fascinate art enthusiasts. His distinctive style, personal struggles, and artistic influence raise common questions about his work and legacy.

What are the defining characteristics of Egon Schiele’s art style?

Schiele’s art is immediately recognizable by its angular, contorted figures and raw emotional intensity. He used sharp, jagged lines to create distorted human forms that express psychological states.

His color palette often featured earthy tones with occasional bright accents. Schiele frequently left portions of his canvas empty, creating a sense of isolation around his subjects.

Self-portraits formed a significant part of his work, displaying uncomfortable poses and unflinching self-examination. His nude figures, both male and female, broke artistic conventions with their explicit, non-idealized portrayals.

How did Egon Schiele’s personal life influence his work?

Schiele’s tumultuous personal life directly informed his artistic output. His difficult childhood and strained relationship with his father shaped his perspective on authority and social norms.

His numerous romantic relationships provided models for his work. His imprisonment in 1912 on charges of seducing a minor resulted in a series of prison drawings that captured his isolation.

The death of his mentor Gustav Klimt and the loss of his wife during the Spanish flu pandemic in 1918 created a sense of mortality that permeated his later works.

What impact did Egon Schiele have on the expressionist movement?

Schiele became a central figure in Austrian Expressionism, pushing the movement toward more psychological and sexual themes. His work expanded expressionism beyond emotional landscapes to include raw human sexuality.

He challenged Vienna’s conservative art establishment with his provocative style. This confrontational approach influenced later expressionists to embrace controversy.

His technical innovations with line and composition opened new possibilities for depicting the human form. Schiele’s influence extended beyond his short lifetime to impact generations of figurative artists.

Which are considered to be Schiele’s most important works, and why?

“Self-Portrait with Physalis” (1912) stands as a masterpiece of psychological intensity, showing Schiele’s ability to convey complex emotions through posture and expression.

“The Family” (1918), completed shortly before his death, represents a more mature period in his work. This unfinished piece shows Schiele with his wife and imagined child, revealing his artistic evolution.

“Death and the Maiden” (1915) demonstrates his skill in depicting intimate relationships charged with symbolic meaning. The painting reflects his complex relationship with women and mortality.

“Cardinal and Nun” (1912) showcases his provocative approach to religious and sexual taboos. This work exemplifies his willingness to challenge social conventions.

How did Schiele’s mentorship under Gustav Klimt shape his artistic development?

Klimt recognized Schiele’s talent early and became his mentor around 1907. He introduced the young artist to potential patrons and exhibition opportunities.

Though Schiele developed a style distinct from Klimt’s golden decorative approach, he absorbed his mentor’s interest in exploring human sexuality. Klimt’s connections helped Schiele establish himself in Vienna’s art world.

Schiele eventually moved beyond Klimt’s influence toward a more angular, emotionally intense style. The relationship between the two artists evolved from mentor-student to mutual respect between colleagues.

What were the legal and societal challenges that Schiele faced during his career?

Schiele’s explicit artworks frequently clashed with the conservative moral values of early 20th century Austria. In 1912, authorities arrested him on charges of seducing a minor and creating immoral drawings.

The seduction charge was dropped, but a judge burned one of Schiele’s drawings in court as a symbolic punishment. This incident highlighted the public’s mixed reaction to his provocative art.

The artist struggled financially for much of his career despite critical recognition. Public tastes lagged behind artistic innovation, making it difficult for Schiele to support himself through his art until his final years.