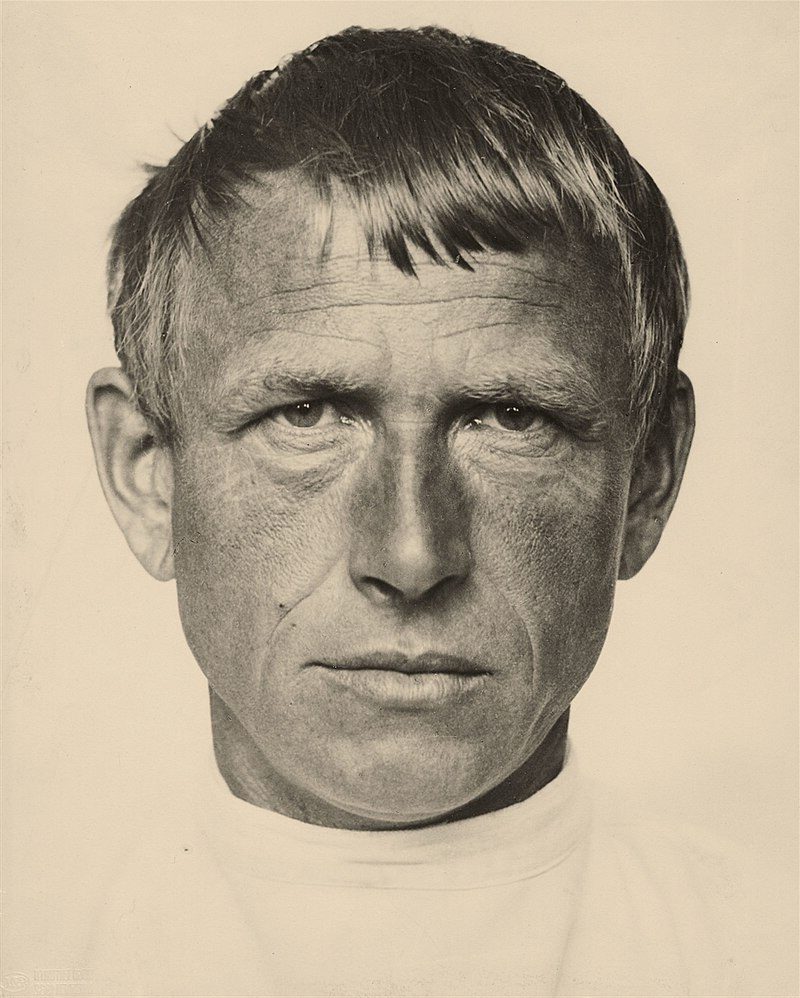

Otto Dix Painter: A Pioneering Voice of German Expressionism

Born: 2 December 1891, Untermhaus, Gera, Germany

Death: 25 July 1969 Singen, Baden-Württemberg, West Germany

Art Movement: Expressionism, New objectivity, Dada

Nationality: German

Teachers: Carl Senff and Richard Guhr

Institution: Dresden Academy of Fine Arts

Otto Dix Painter: A Pioneering Voice of German Expressionism

Life and Career of Otto Dix

Otto Dix became one of Germany’s most important artists through his unflinching portrayal of war and society. His work evolved through several distinct periods, shaped by his wartime experiences and the dramatic political changes in Germany during his lifetime.

Early Years and Education

Otto Dix was born on December 2, 1891, in Untermhaus, Germany to a working-class family. His mother, a seamstress, encouraged his early artistic talents.

War, 1932, by Otto Dix

At age 14, Dix apprenticed with landscape painter Carl Senff, learning foundational painting techniques. He later attended the Dresden School of Arts and Crafts from 1909 to 1914, where he developed his technical skills.

During this formative period, Dix was influenced by Nietzsche’s philosophy and contemporary art movements like Expressionism and Futurism. His early works showed experimentation with various styles before developing his own distinctive approach.

These educational experiences provided Dix with the technical foundation that would later allow him to create his powerful, socially critical works.

World War I Experience

Dix volunteered for the German army in 1914, serving as a machine gunner on both the Western and Eastern fronts. This experience profoundly shaped his art and worldview.

During his service, he created numerous sketches documenting the brutal realities of trench warfare. Dix witnessed horrific scenes that would later fuel his most powerful works.

He was wounded several times and eventually earned the Iron Cross for his service. Despite the trauma, Dix maintained that experiencing war firsthand was necessary for his artistic development.

After the war, Dix processed these experiences through his art. His haunting series “Der Krieg” (The War) featured disturbing, realistic depictions of wounded soldiers, decomposing bodies, and devastated landscapes.

These war-themed works established Dix’s reputation for unflinching social commentary and marked his transition to the New Objectivity movement.

Weimar Republic Period

During the 1920s, Dix emerged as a leading figure in the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement. This period represented his most productive and commercially successful years.

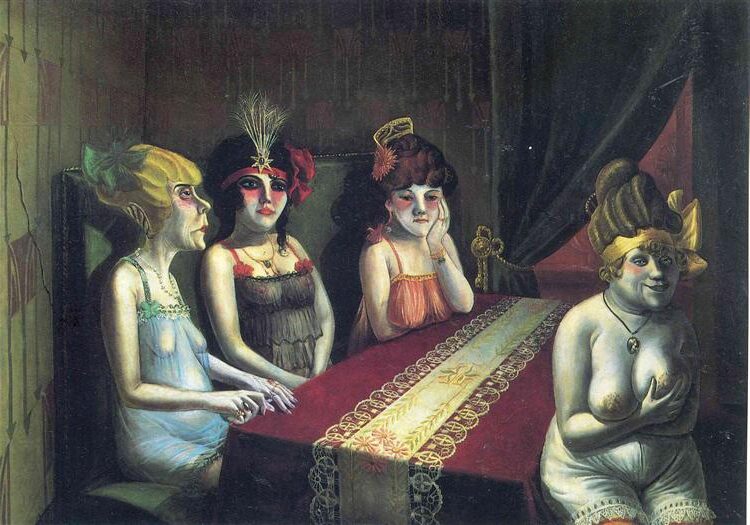

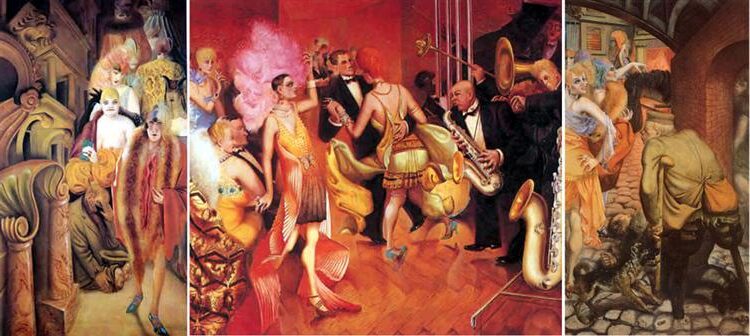

Salon, 1927, by Otto Dix

In 1919, he co-founded the Dresden Secession Group and began teaching at the Dresden Academy. His works from this time critically examined post-war German society with brutal honesty and technical precision.

Dix’s most famous paintings from this era include “Metropolis” (1927-28) and “Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden” (1926). These works captured the decadence, inequality, and social tensions of Weimar Germany.

His satirical portraits of prostitutes, war profiteers, and disabled veterans challenged viewers and authorities alike. Though controversial, his work gained recognition, and by 1927, he was appointed professor at the Dresden Academy of Fine Arts.

Nazi Era and Aftermath

When the Nazis seized power in 1933, Dix’s career faced immediate obstacles. The regime labeled his work “degenerate” and removed him from his teaching position at the Dresden Academy.

In 1937, the Nazis included 260 of Dix’s works in their infamous “Degenerate Art” exhibition. Many of his paintings were later destroyed or sold off by the regime.

Dix retreated to Lake Constance, adopting a less provocative style focused on landscapes and religious allegories. This strategic shift allowed him to continue working while avoiding direct confrontation with authorities.

Despite this adaptation, he was briefly drafted into the Volkssturm (people’s militia) in 1945 and was captured by French troops, spending several months as a prisoner of war.

Later Years and Legacy

After World War II, Dix returned to his more critical style. He received numerous honors, including the Federal Cross of Merit in 1959.

Wounded Soldier, 1924, by Otto Dix

Dix divided his time between Dresden in East Germany and Lake Constance in West Germany. This unique position allowed him to serve as a cultural bridge during the Cold War era.

In his later works, he revisited war themes, creating pieces like “War Triptych” (1959-1961) that connected his WWI experiences with the newer horrors of WWII.

Otto Dix died on July 25, 1969, in Singen, West Germany. His unflinching artistic vision influenced generations of artists who address social issues through their work.

Today, Dix is recognized as one of the most important German artists of the 20th century. His works serve as powerful historical documents of German society through its most turbulent periods.

Artistic Style and Influences

Otto Dix developed a distinctive artistic style characterized by unflinching realism and technical precision. His work evolved through several influential art movements while maintaining his unique perspective on society and human experience.

New Objectivity Movement

Dix became a leading figure in the New Objectivity (Neue Sachlichkeit) movement that emerged in Germany after World War I. This movement rejected expressionism in favor of a harsh, unsentimental realism that depicted the brutal realities of German society.

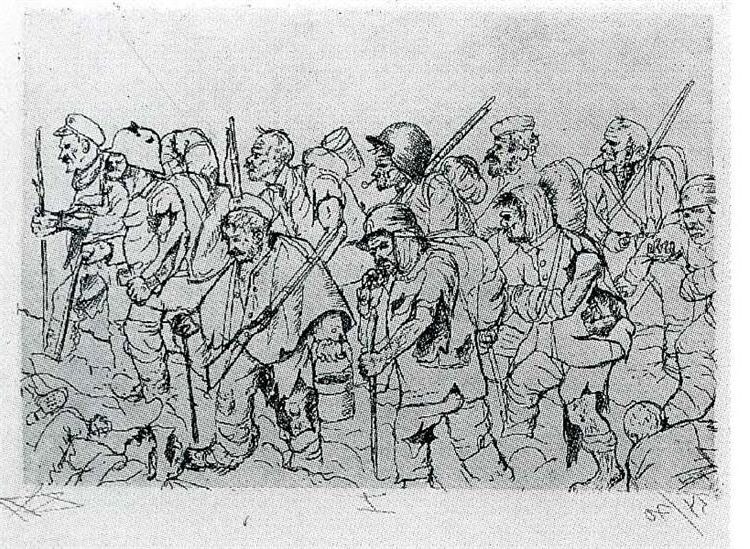

Battle Weary Troops Retreating – Battle of the Somme, 1924

Dix’s paintings during this period featured sharp, precise lines and meticulous detail. He portrayed his subjects without idealization, often emphasizing unflattering characteristics and social decay.

His 1923 work “The Match Seller” exemplifies this approach, showing a disabled war veteran selling matches on a street, ignored by passersby. This painting highlights the movement’s focus on social critique and documentation.

Dix’s technical approach included using Old Master techniques like glazing while applying them to contemporary subject matter. This combination created a disturbing clarity that became his signature style within the movement.

Dadaism and Expressionism

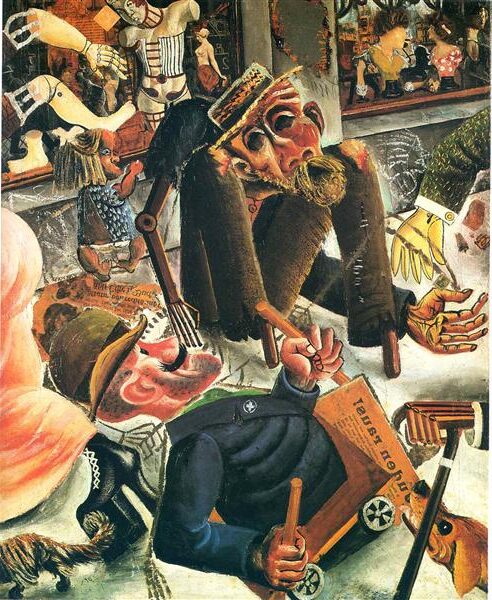

Before fully embracing New Objectivity, Dix experimented with Dadaism and Expressionism in his early career. Dadaist influence appears in his provocative, anti-establishment attitudes and occasional use of collage techniques.

His 1920 painting “Prague Street” shows this transitional period, combining expressionist distortion with the emerging precision of his later work. During this phase, Dix used exaggerated colors and forms to convey emotional intensity.

The artist maintained expressionist elements throughout his career, particularly in his use of color to evoke psychological states. This can be seen in works like “Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden” (1926), where the subject’s inner state is revealed through subtle color choices.

His connections to the Dresden Secession group also shaped his artistic development. Though Dix never fully embraced abstract expressionism, these early influences remained visible in his compositional choices.

War’s Impact on Art

World War I profoundly shaped Dix’s artistic vision. As a machine gunner who saw extensive combat, he created some of the most powerful anti-war art of the 20th century.

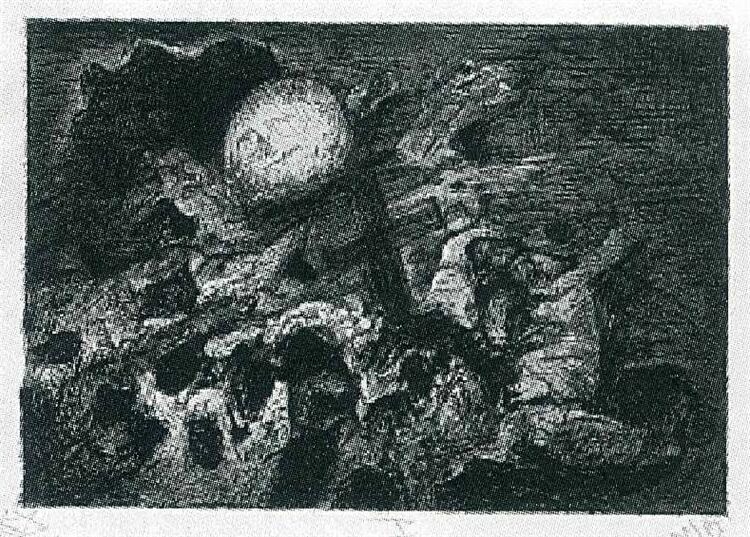

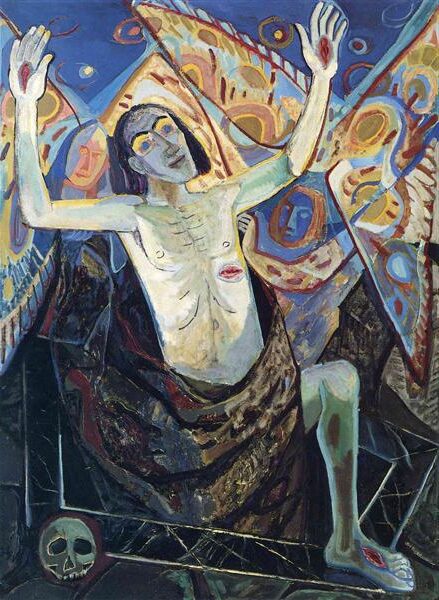

The War, 1924, by Otto Dix

His 50-print series “Der Krieg” (The War) from 1924 depicts the horrors of trench warfare with unflinching detail. These etchings show decomposing bodies, shell-shocked soldiers, and devastated landscapes with clinical precision.

“The War Triptych” (1929-1932) stands as his masterpiece on this theme. Using a format traditionally reserved for religious subjects, Dix presents war as a modern hell. The central panel shows soldiers in a destroyed landscape, while side panels depict troops marching to battle and returning as wounded survivors.

Dix’s war paintings combine journalistic documentation with symbolic elements. He used realistic details from his experience while incorporating dreamlike, nightmarish qualities that convey psychological trauma.

Portraiture and Depictions of Society

Portraiture became a central focus of Dix’s work, allowing him to create incisive studies of Weimar Germany’s social classes. His portraits often revealed uncomfortable truths about his subjects and society at large.

Dix painted prostitutes, war profiteers, and the bourgeoisie with equal technical skill but varying degrees of sympathy. His 1925 portrait series of war veterans with facial disfigurements challenged viewers to confront war’s lasting consequences.

His technique incorporated Renaissance methods like using multiple thin glazes of oil paint to achieve luminous skin tones. This traditional approach created an unsettling contrast with his modern, often disturbing subject matter.

When the Nazis came to power, they labeled Dix’s work “degenerate.” During this period, he shifted to landscape painting and allegorical subjects, adapting his style while maintaining his critical perspective. After World War II, he returned to his earlier themes with renewed intensity.

Notable Works

Otto Dix created powerful artworks that documented German society before, during, and after World War I. His unflinching style captured the brutality of war and the decadence of Weimar Republic society with technical mastery and psychological insight.

The Trench Warfare Series

Dix’s most haunting works emerged from his experiences as a machine gunner in World War I. His 1924 portfolio of etchings “Der Krieg” (The War) contains 50 prints showing the grim reality of trench warfare.

Stormtroopers Advance Under a Gas Attack, 1924, by Otto Dix

The series depicts decomposing bodies, destroyed landscapes, and shell-shocked soldiers with unflinching detail. In “Storm Troopers Advancing Under Gas,” Dix shows soldiers wearing gas masks moving through a hellish landscape.

Unlike glorified war paintings, Dix presented war’s true horror. The German military considered these works “anti-military” and “defeatist.”

These etchings used aquatint and acid techniques to create stark contrasts between light and dark, emphasizing the nightmarish quality of modern warfare.

Portraits of the Weimar Era

Dix painted numerous portraits during the 1920s that revealed the social divisions in post-war Germany. His subjects ranged from war veterans to prostitutes and wealthy industrialists.

In “Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden” (1926), Dix captured the “New Woman” of the era with her short hair, monocle, and cigarette. The portrait emphasizes her angular features and masculine styling.

His portrait technique often exaggerated features to reveal psychological truths. He used thin glazes of oil paint in the style of Old Masters while incorporating modern elements.

Dix’s portraits show both fascination and criticism of Weimar society. He portrayed the wealthy with the same unforgiving eye he used for society’s outcasts.

Metropolis (Triptych)

“Metropolis” (1927-28) stands as Dix’s most ambitious painting of urban life. Created in a traditional triptych format typically used for religious scenes, Dix instead depicts the decadence of 1920s Berlin.

Metropolis, 1927–1928, by Otto Dix

The central panel shows jazz-age revelers dancing while disabled war veterans remain ignored on the street. The side panels contrast prostitutes with wealthy patrons entering a nightclub.

Dix used bold colors and distorted proportions to create a sense of moral decay. The painting’s composition guides viewers through different social classes coexisting in the modern city.

This work captures the extreme inequality of Weimar Germany between those profiting from the economic crisis and those suffering from it.

Prague Street

“Prager Street” (1920) represents Dix’s early New Objectivity style. The painting shows wounded war veterans begging on a Dresden street as indifferent civilians pass by.

Dix created a troubling scene with precise detail. A legless veteran crawls along the sidewalk while a blind man sits with a sign. Well-dressed pedestrians ignore them completely.

The artist used an unsettling color palette dominated by reds and browns. Architectural elements appear slightly distorted, creating an uncomfortable perspective.

This painting directly confronts German society’s willingness to forget the human cost of war. Rather than honoring veterans, the scene shows them discarded and forgotten.

Frequently Asked Questions

Otto Dix remains one of the most influential German artists of the 20th century. His distinctive style and powerful commentary on war and society continue to fascinate art enthusiasts and historians alike.

What are the defining characteristics of Otto Dix’s painting style?

Otto Dix developed a harsh, realistic style characterized by unflinching depictions of human subjects. His work features precise, often grotesque details that reveal uncomfortable truths about his subjects.

Dix frequently used sharp lines and exaggerated features to create unsettling portraits. His color palette typically included acidic, harsh tones that enhanced the psychological impact of his paintings.

Many of his works incorporate elements of both traditional Renaissance techniques and modern expressionism. This unique combination allowed Dix to create images that feel both timeless and distinctly of their era.

Which historical events significantly influenced the work of Otto Dix?

World War I had the most profound impact on Dix’s artistic development. His firsthand experience as a machine gunner on both the Western and Eastern fronts shaped his view of humanity and society.

The Weimar Republic period (1919-1933) provided Dix with rich subject matter for social critique. The economic hardship, political instability, and moral ambiguities of this era appear frequently in his paintings.

The rise of Nazism in Germany directly affected Dix’s career. In 1933, he was dismissed from his teaching position, and his work was labeled “degenerate art” by the Nazi regime.

Can you name some of Otto Dix’s most famous paintings?

“The Trench” (1923) stands as one of Dix’s most powerful war paintings, depicting decomposing bodies in a destroyed battlefield. Unfortunately, this work was lost during World War II.

“Metropolis” (1927-28), a triptych portraying the decadent nightlife of 1920s Berlin, remains one of his most recognized works. Its vibrant scenes capture the extremes of Weimar society.

“Portrait of the Journalist Sylvia von Harden” (1926) shows Dix’s mastery of portraiture. This striking image of a modern woman smoking at a café became an iconic representation of the era.

“War” (1929-32), another triptych, presents a brutal vision of warfare inspired by Matthias Grünewald’s Isenheim Altarpiece. Its disturbing imagery reflects Dix’s traumatic war experiences.

How did Otto Dix contribute to the New Objectivity movement in art?

Dix became a leading figure in Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity), a movement that emerged in Germany after World War I. He helped define its unsentimentally realistic approach to subject matter.

His technical precision and unflinching portrayal of social realities embodied the movement’s rejection of expressionism’s emotional extremes. Dix’s work demonstrated a cold, clinical gaze at post-war German society.

Dix’s paintings of war veterans, prostitutes, and the urban bourgeoisie exposed the hypocrisies and contradictions of his time. This social critique aligned perfectly with New Objectivity’s mission to reveal uncomfortable truths.

What was Otto Dix’s role in World War I, and how did it impact his artwork?

Dix volunteered for the German army in 1914 and served as a machine gunner on both fronts. He participated in the Battle of the Somme and received the Iron Cross for his service.

Throughout the war, Dix created hundreds of drawings documenting his experiences. These sketches later informed his more elaborate post-war paintings depicting the horrors of combat.

The psychological trauma of warfare became Dix’s primary artistic focus for years. His unforgettable images of mutilated soldiers, rotting corpses, and devastated landscapes stand as powerful anti-war statements.

How have Otto Dix’s paintings been received and interpreted by art historians?

Initially, Dix’s work shocked audiences with its graphic content and unflinching realism. Many critics found his paintings too disturbing or politically provocative.

After World War II, appreciation for Dix grew as his anti-war message resonated with post-war sensibilities. Art historians began recognizing his technical skill and psychological insight.

Today, Dix is widely regarded as one of Germany’s most important artists of the 20th century. His work is valued for its historical documentation, technical brilliance, and moral stance against war and social inequality.